Bringing Surrealism to the Ballet: Diaghilev and Miro

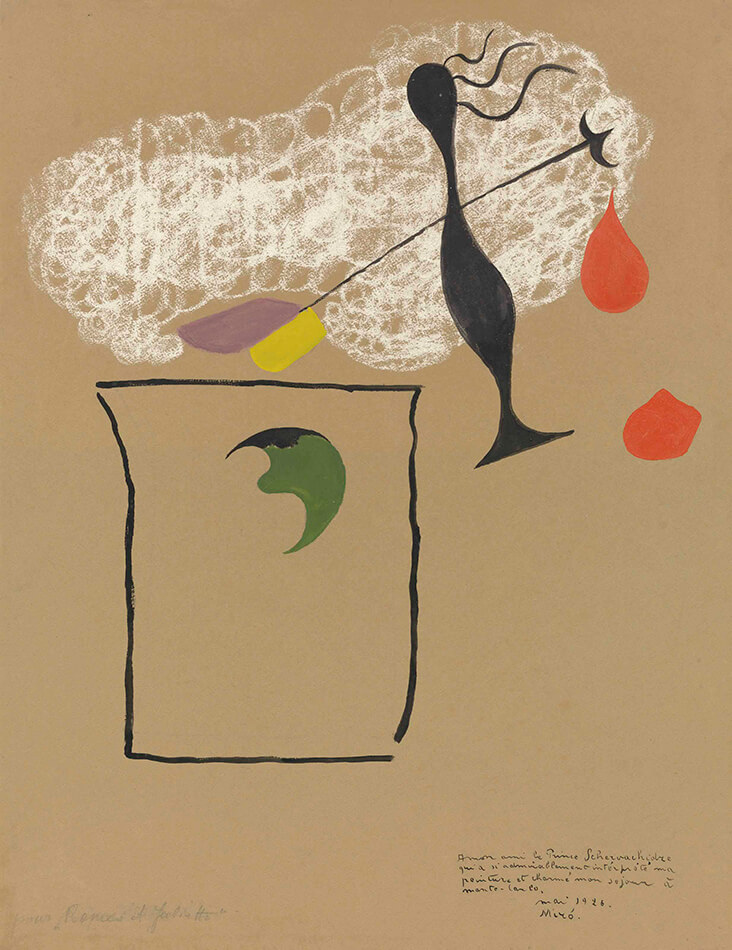

Joan Miro, simple, minimal costume design for Sergei Diaghilev’s Romeo et Juliette: Projet de Scene, 1926

When Sergei Diaghilev founded the Ballets Russes in Paris in 1909, he knew he wanted to dazzle and amaze audiences with something entirely new. “Surprise me!” was the famous maxim he would exclaim with glee to artists approaching him with new ideas, but little did he know the treasures that would await him in the years to come. In 1926 he collaborated with Surrealist artists Joan Miro and Max Ernst on a radical and unconventional production of Romeo and Juliet that astounded ballet audiences around the world. The experience was so profound for Miro that he would go on to design further costumes for the Ballets Russes in the years to come.

Diaghilev first started planning a true-to-text traditional production of Romeo and Juliet to be performed in Monte Carlo in the 1920s, with music composed by the up-and-coming English composer Colin Lambert, and set designs by Lambert’s friend Christopher Wood. But somewhere along the line Diaghilev had a dramatic change of heart, deciding instead to break with convention and try something more daring and unconventional. His new concept was to tell the story of a ballet company rehearsing Romeo and Juliet, which he titled Romeo at Juliette: Projet de Scene (Romeo and Juliette: Behind the Scenes). He needed sets and costumes that would reflect the same spirit of playful experimentation, so he abandoned Wood’s designs, instead inviting the renowned Surrealists Joan Miro and Max Ernst to step in.

Even before taking up work with Diaghilev, Miro was fascinated by the transient movement of dancers, which he had tried to capture with slim, elemental lines and bold streaks of colour in works such as Dancer, 1925. When starting out with the Ballets Russes, Miro and Ernst revelled in the informality of Diaghilev’s backstage theme, choosing to keep the stage itself as plain and simple as possible. Ernst painted curtains to represent night and day, while Miro included a brightly painted front cloth. Onto the stage itself Miro introduced unexpected items such as coat racks, a pink dressing gown, ballet barre and towel rails, along with a glowing, phosphorescent star to light up the darkness. Miro treated the dark backdrop of the stage much like a sheet of paper or canvas, into which various collaged elements could be introduced, mirroring the language of his abstract Surrealist paintings.

The costumes Ernst and Miro designed were equally as experimental – characters were dressed in the colourful, comfortable clothing of a rehearsal room rather than any elaborate or ornate costume, making a sharp break with ballet convention. To further add to the Surrealist theme, they envisioned Romeo and Juliet flying away together in an aeroplane as the final scene, dressing them in airmen’s caps and leather coats.

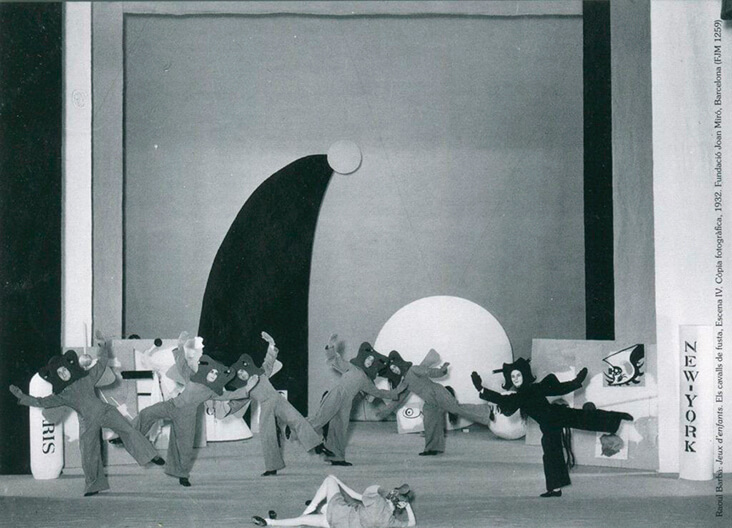

Joan Miro, costume for the ‘Spinning Top’ in Leonide Massine’s ballet Jeux d’Enfants, 1932. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The show’s premiere at the Theatre de Monte Carlo was surprisingly well received, but it was the performance in Paris that caused the wildest uproar. Members of the Surrealist group criticised Miro and Ernst of selling out to capitalism, storming the theatre with an angry shower of catcalling, whistling and violent protest, which ended when police stormed the theatre. Diaghilev revelled in the scandal and sensationalism, which acted as a powerful promotional tool for the Ballets Russes, and helped bring the work of Miro and Ernst to a wider audience. Miro went on to create various works of art inspired by the theme of Romeo and Juliet, including the artwork Pour “Romeo et Juliette”, 1926, which he dedicated to his friend, Prince Shervashidze, who had assisted Miro with the painting of his Romeo et Juliette set designs.

Although Diaghilev passed away in 1929, Miro went on to collaborate further with the Ballets Russes in the 1930s, famously designing costumes for Leonide Massine’s ballet Jeux d’Enfants in 1932. Miro designed all the costumes and sets as well as painting a front curtain, props and a series of paintings to adorn the stage. His designs this time around aligned more closely with his painting style than Romeo et Juliette, featuring trademark Spanish earthy colours and wild, expressive streaks of colour. One of his most celebrated costumes was the ‘Spinning Top’, featuring bold, encircling bands of intense colour to enhance the character’s spiralling motion.

Through his work with the ballet, Miro was able to extend his artistic language into surprising and unexpected directions, allowing him to extent into a consideration of space, movement and energy. Miro’s theatrical design work had a profound impact on his later art, featuring striking figurative forms in dazzlingly bright colours which hover suspended in space, capturing the same excitement and energy of dancers caught mid-motion on stage.

Leave a comment