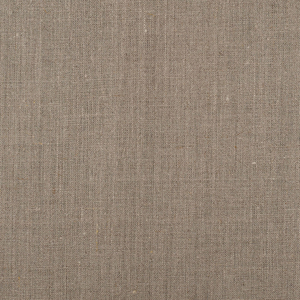

FS Colour Series: Egyptian Yellow Inspired by Pablo Picasso’s Luminous Gold

One of the greatest colourists of all time, Pablo Picasso brought radiant yellows like that of EGYPTIAN YELLOW linen into many of his most famous artworks, infusing into them a golden, glowing light. Born in Spain before relocating to France, Picasso remained patriotic to his home country throughout his career, and he would have been well aware of this warm golden colour’s associations with the Spanish flag. But he also loved how golden yellow shades could mimic the luminosity of gold in his paintings, harking back to the great Spanish Renaissance and Baroque traditions that inspired so much of his art.

Picasso was precociously talented from a very young age, demonstrating an ability that was well beyond his years. Raised in Malaga, Spain, his father was a painter and art teacher, who taught his son art lessons at home, training the young prodigy to excel in academic drawing and painting. Recognising his son’s extraordinary talent, he sent Picasso to formal art lessons from the age of 11, and took him on regular trips to Madrid to see and copy works by the Spanish Old Masters.

When the family relocated to Barcelona, Picasso continued to develop his artistic skills at the city’s School of Fine Arts from the tender age of 13. He also began frequenting the city’s lively bohemian café culture, meeting some of the world’s leading artists including Edvard Munch and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, whose ideas informed his early paintings. Throughout the early 1900s Picasso travelled widely, exploring the dark underbellies of Madrid and Paris which first began to appear in his paintings.

Colour was vital to the development of Picasso’s early work, in spells famously known as his ‘Blue Period’ followed by the pink-tinged ‘Rose Period.’ Following these early phases Picasso then moved on to a livelier array of ambient, warm colours, often conveying performers and circus figures caught in private moments of reverie. The early painting Harlequin with Glass, 1905, was made during this time. Set in a moody, brown backdrop, sonorous autumnal shades of moss green, burnt orange and honey yellow form a chequered pattern across the harlequin’s chest, while the model is based on Picasso as he likens himself to the playful, yet melancholic clown finding his way in the world.

By 1906 Picasso was slowly abandoning realism in favour of experimental Cubist styles alongside his close friend Georges Braque. Woman and Pears, 1909, typifies Picasso’s early Cubist work, with broken perspective and faceted, angular forms representing the fragmented nature of human perception. Though his Cubist colour palette was restricted, golden yellows were a defining feature, as seen here, taking on the weight and solidity of glossy, varnished wood and resembling the African carvings and masks he was so taken with at the Parisian Ethnographic Museum.

Through his competitive friendship with Braque, Picasso continued to push further towards innovative, avant-garde ways of working within the Cubist oeuvre, edging ever closer to a flattened, abstract language of dancing colour and light. In his later Cubist works Picasso’s irreverent, child-like spirit began to roam free as he played with cut out and collaged shards of brilliant colour alongside lively textures and patterns. Three Musicians, 1921, replicates the cut edges of collage in paint, as flat shapes are arranged into a complex, layered composition resembling the energy and movement of both the musicians and the music they are playing. The dazzling red and yellow checked print of another harlequin’s costume pulls our eye to the heart of the scene, where a guitar’s curvy, voluptuous form is painted in sticky caramel yellow, suggesting the mellow warmth of the music it makes.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Picasso continued to experiment with innovative and novel approaches to imagery, moving beyond the sharp, angular language of Cubism to a distorted Surrealist approach with sinuous, curvaceous and flowing lines. Women and still life subjects were recurring motifs, while sometimes the two were collapsed into one; in Still Life, Basket of Fruits and Bottle, 1937, a humble display of ordinary objects is painted with sculptural, suggestive forms reminiscent of the female body. Pale turquoise blue expands into fresh open space across the background, allowing ripe, juicy fruit to stand out with the zesty and dazzling radiance of the sun. Warped black and white zebra stripes wrap around the fruit with the dynamism of draped fabric, further emphasising the golden, fleshy glow of the fruit inside.

Leave a comment