Fabric and Fibres in Contemporary Art: An Introduction

The role textiles play in contemporary art is a hot topic right now, one that countless galleries and publishers around the world are keen to pick up on. Some of the most publicised, recent examples include Turner Contemporary Gallery in Margate’s Entangled: Threads and Making in 2017, Tate’s stellar and widely popular tribute to the masterful weavings of Anni Albers in 2018-19, and the anthology, Vitamin T: Threads and Textiles in Contemporary Art, published in early 2019. What all these tributes to textiles have in common is a desire to erase preconceived ideas about art materials, as well as the pressing need to celebrate the vitally important role of textile artists throughout history, many of whom have been women, who were sidelined or neglected by art historians – it is time they had their voices heard.

An ancient Peruvian cloth from the UCLA Fowler Museum’s noteworthy collection of Precolumbian textiles

Weaving and textiles as a creative form of communication can be traced back to ancient times, something Anni Albers and her contemporaries in the early 20th century Bauhaus were keen to emphasise. As Albers pointed out in her timeless publication On Weaving, 1965, in ancient Peru textiles were not simply functional, but an early and highly sophisticated form of language. She observes, “In Peru, where no written language … had developed even by the time of the Conquest in the sixteenth century, we find … one of the highest textile cultures we have come to know.” It is perhaps no surprise then, that the word ‘text’ is derived from the Latin word ‘textus’, meaning ‘woven’, suggesting a link between language and fabric that runs deep into the core of civilisation.

The world-renowned Bayeux Tapestry is another potent early example of textile art made in around 1070, documenting the Norman Conquest of England, much in the way paintings of later generations would illustrate the retelling of history. Medieval embroidery was a much-prized luxury, made by both men and women; it was only during the Renaissance period that divisions between “masculine” art forms such as painting, sculpture and architecture were separated from the domestic, or supposedly “feminine” realms of fabric, needlework and embroidery as art institutions became increasingly conservative – by the 18th century, the Royal Academy had entirely banned needlework from display.

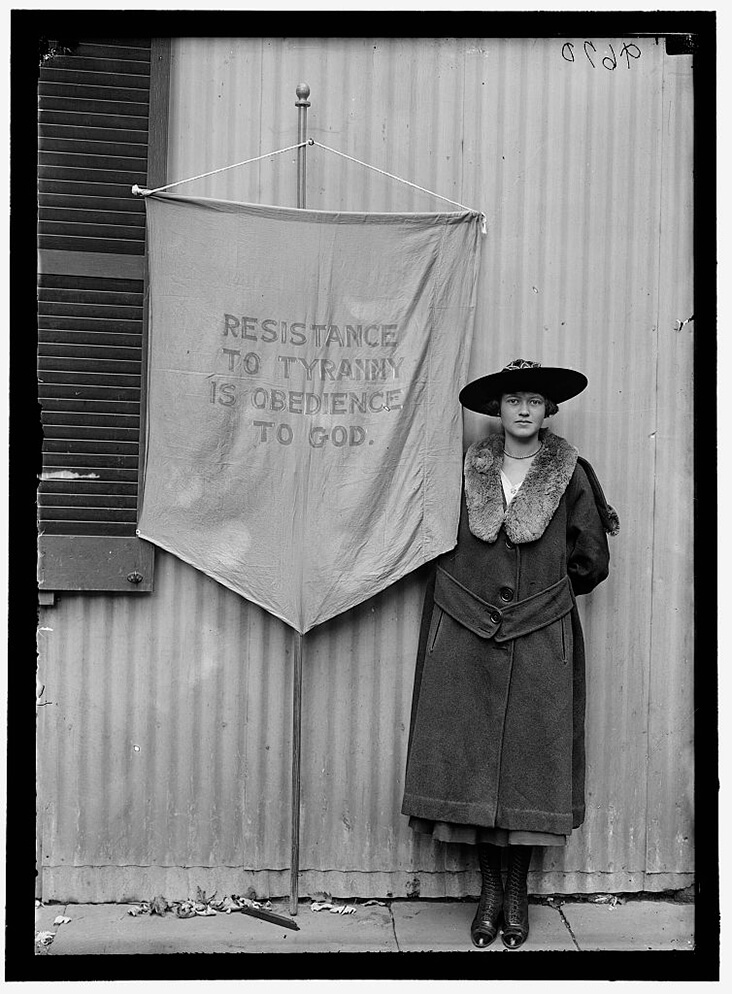

As the industrial revolution shifted the making of crafts from necessity to luxury, pursuits of weaving, embroidery and textiles became increasingly associated with women’s leisure pursuits and were taken less seriously by staunchly traditional, male-led art institutions. But as Roszita Parker argues in The Subversive Stitch, 1984, women making textiles, tapestries and embroideries were often involved in quiet forms of protest that easily crossed the line into art, sewing or weaving together stories about their personal struggles or family lives, something the Craftivism phenomenon of recent decades has picked up on. Parker also highlights how women involved with the early 20th century suffrage sewed together eye-catching, embroidered banners that spoke of frustrations and oppressions in a visual language that was entirely their own. Arguing for the strength and longevity in such forms of protest, Parker writes, “Femininity and sweetness are part of women’s strength…Quiet strength need not be mistaken for useless vulnerability.”

In the same century, Anni Albers was one of a generation of aspirational women pushed by male leaders of the Bauhaus into the “women’s” section of weaving, but who turned the medium on its head, transforming it into a powerful, tactile and sensuous form of communication. Ground broken by Albers and her contemporaries paved the way for the Fiber Art Movement of the United States in the 1960s and 70s, led by feminist artists who were associated with the Women’s Movement, including Judy Chicago, Lenore Tawney and Sheila Hicks, artists who tested and stretched the boundaries of fibres and their ability to challenge the patriarchal systems of society through an innately feminine language.

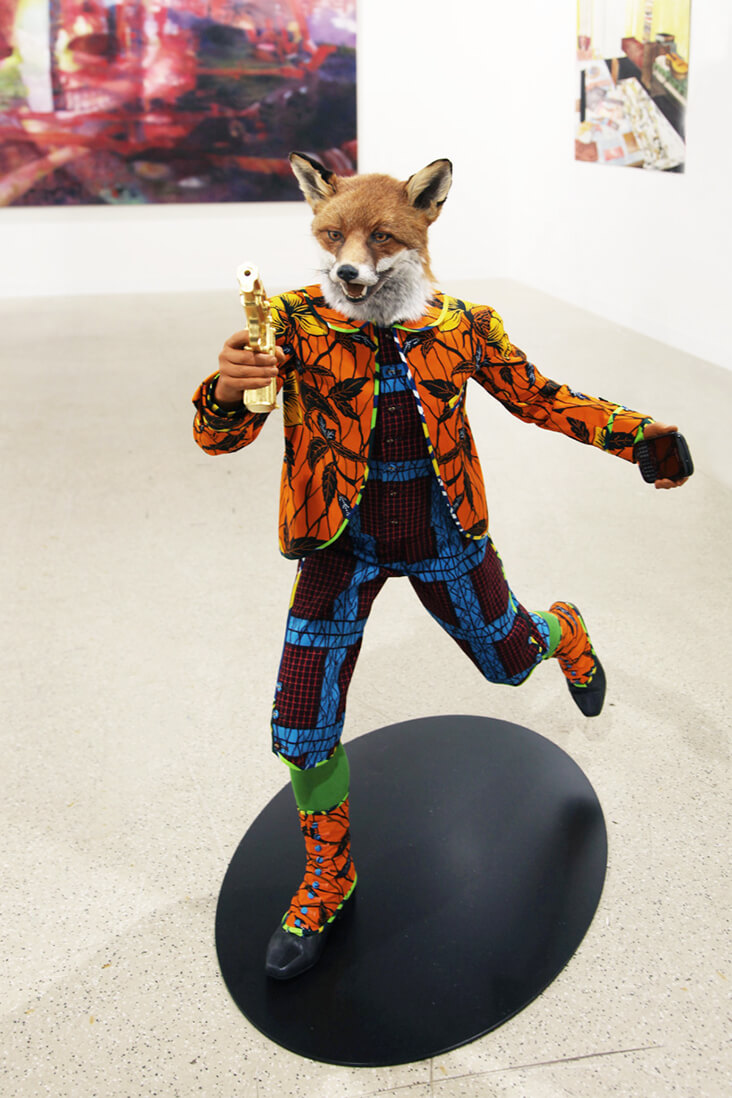

Since this time, artists of all genders have continued to experiment with fabric and fibres in wildly adventurous and unprecedented ways, from Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s epic blankets of fabric that cover or encircle buildings, landmarks and islands, to Phyllida Barlow’s decadent, excessive assemblages made from warm, earthy tones and Yinka Shonibare’s exotically bright, African textiles, which have become all-encompassing sculptures and installations. In this new series, we will delve into the most adventurous of today’s fabric and fibre artists, examining their awe-inspiring, endlessly inventive practices, the range of materials, textures, colours and patterns they have explored and the ways they have blasted the field wide open for the next generation to come.

One Comment

Lynette Pflueger

You have given fibre lovers a wonderful blog, thank you! btw the top image is a minime by Sheila Hicks