Christian Dior: Post-war Glamour

“It was as if Europe had tired of dropping bombs and now wanted to let off a few fireworks.”

Christian Dior’s meteoric rise to success came in the late 1940s, at a time when post-war austerity and rationing led fashion towards clean lines and utilitarian styles. His designs came as a revelatory shock, re-introducing glamour, femininity and luxury with full skirts, nipped-in waists and his trademark soft, 18th century pastels, a style that came to define the 1950s. Carmel Snow, former editor in chief of Harper’s Bazaar, coined the term “New Look” to describe his aesthetic, exclaiming in response to his breakout collection in 1947, “It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian! Your dresses have such a new look!”

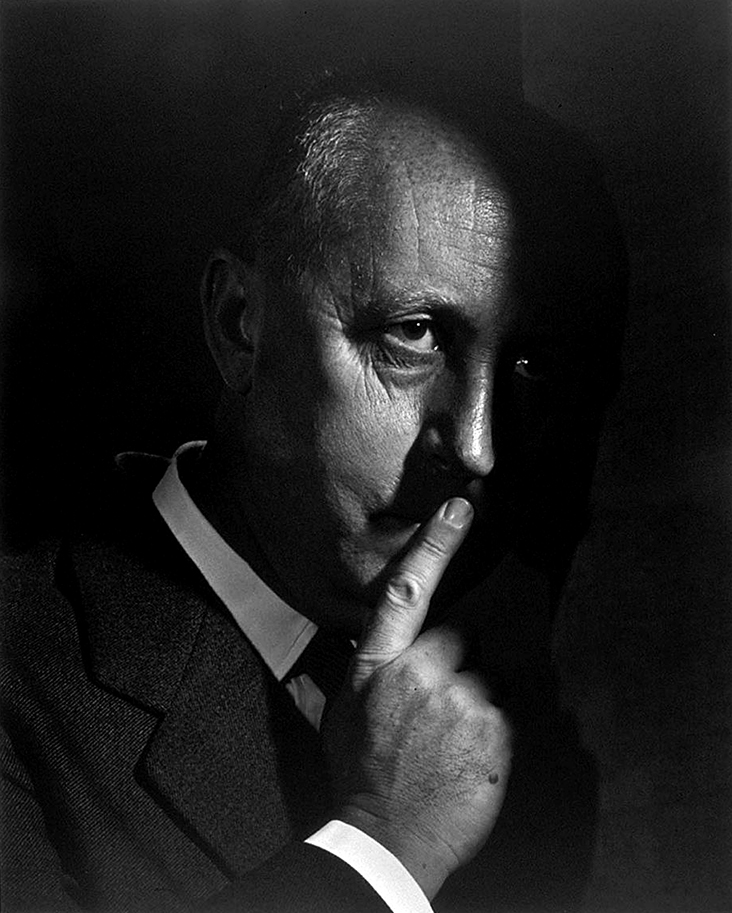

Born in the seaside town of Granville on Normandy coast in 1905, Dior was one of five children. The son of a wealthy fertiliser manufacturer, Dior’s upbringing was stable and secure and his artistic inclinations drew him towards “anything that was sparkling, elaborate, flowery or frivolous,” particularly flowers and plants. Following a move to Paris when Dior was just 5, his mother’s Belle Epoque style was an endless source of fascination, remaining with him into adulthood. Something of a tyrant, Dior’s father pushed his sensitive son towards the study of political sciences at the Ecole des Sciences Politiques in Paris, hoping he would join the Diplomatic Corps. But as a student in Paris, Dior was more naturally drawn to the lively, bohemian art circles, befriending Jean Cocteau, Max Jacob, Salvador Dali and Christian Berard, artists, designers and illustrators who would have a profound impact on his career.

Following his graduation, Dior persuaded his father to support him with the establishment of an art gallery in Paris, where he tried to sell artworks by avant-garde painters including Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, although sales were minimal. When the Great Depression struck, Dior’s life was ripped apart; his father’s business collapsed and he was forced to sell his son’s gallery, while both Dior’s mother and brother died shortly after. Cast adrift, Dior lost his apartment and had to sleep on a friend’s floor. Living through these dark times inevitably hit Dior’s health, and he contracted a severe case of tuberculosis, taking a whole year to recover.

Starting from rock bottom, Dior dusted himself down and began again. Through his friendship with the illustrator Christian Berard, Dior found work as a fashion illustrator, and before long his drawings were being published in local Parisian newspapers. His drawings caught the eye of Swiss designer Robert Piquet, who offered Dior a position in his design studio. Initial work with Piquet led Dior to find more autonomy as a primary designer in Lucien Lelong’s design studio, alongside Pierre Balmain.

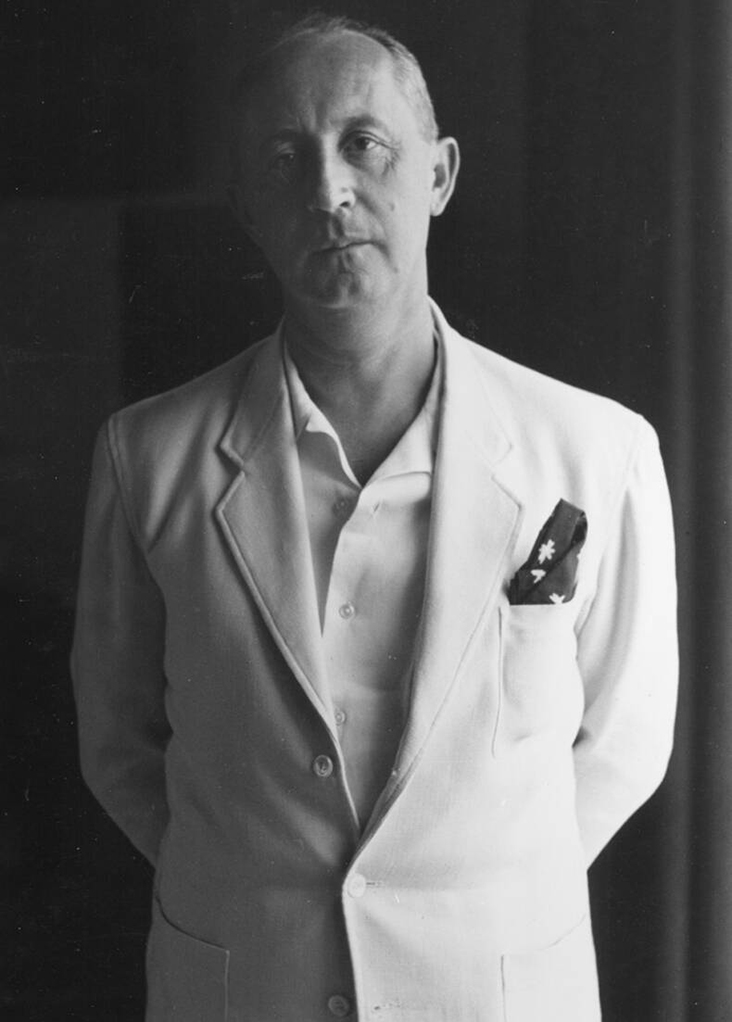

Called for military service in 1940, Dior spent two years carrying out farm work; following its completion in 1942 he was quick to return to Paris. Like many designers during the Second World War, Dior had to search for opportunities where he could find them. Although he later faced criticism for his choices, Dior, along with various other fashion designers, found a steady market for haute couture in the wives of Nazi officers and the Berlin plutocracy, a controversial, problematic move, but one he justified as the only way to keep the fashion industry in Paris afloat throughout the war.

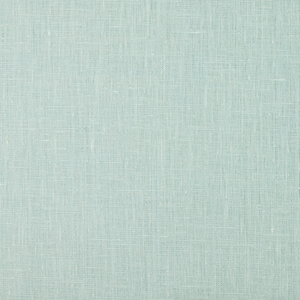

When Dior’s friend, Balmain set up his eponymous business in 1945, Dior was spurred on by the competition. With financial support from the cotton fabric magnate Marcel Boussac, who had empty factory spaces sitting idle following the war, Dior was able to set up his own establishment at 30 Avenue Montaigne Paris in 1946, when he was 41 years old. Capitalising on the art world and commercial contacts he had been building up over the past few decades, he hit the ground running, quickly garnering attention for his sumptuous, feminine styles in sumptuous, meltingly soft shades of rose, pale grey and pale blue. 1947 was a landmark year for Dior, when he presented his first fashion collection, with over 90 different looks, all centred around waspish waists, fitted jackets and full, A-line skirts in calf-length, paired with clean lines and streamlined elegance, a “New Look” at the brink of a new era, one which appealed to clients who dreamed nostalgically of the extravagance and glamour of “the good old days.”

Dior’s feminine silhouettes moved away from the boyish, loose cuts and trousers of Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel, whose designs had freed women from the confines of corsetry. While Dior’s designs were not as restrictive as 19th century corsets, many women, particularly feminists, saw his excessively ornate, deliberately decorative fashion as a step backwards. “We abhor dresses to the floor! Women, join in the fight freedom in the manner of the dress!” shouted women from the Little-Below-the-Knee-Club, who staged a much publicised protest against Dior’s New Look in Chicago. Others reacted strongly against Dior’s indulgent, abundant use of fabric during times of post-war rationing, (some of his dresses used up to 80 yards of fabric), when strands of society were struggling to survive, including the League of Broke Husbands, a group of men in Georgia who tried to get 30,000 signatures calling for a ban on Dior’s full-skirted designs. Chanel, who had spearheaded the boyish, sporty silhouettes of the 1920s and 30s, soon found her designs being upstaged by Dior’s ostentatious swathes of decadent fabric, to which she uttered in jealous despair, “Dior doesn’t dress women, he upholsters them!”

Despite the controversies, Dior was inundated with a series of high-profile customers, including Rita Hayworth and Margot Fonteyn, while his opulent luxury heralded a return to Paris’ pre-war glory days as the home for fabulous haute couture. For many women his designs were a welcome relief from the stark simplicity of war-time uniforms, allowing them to feel truly feminine again. Such was the luxury of his design wear that he was even invited to present his designs to the British royal family, although King George V forbid princesses Elizabeth and Margaret from wearing Dior just after the war, in fear they might offend a public accustomed to austerity. Even so, in the years that followed Princess Margaret would become one of Dior’s most regular customers. His designs were also worn by Marlene Dietrich in Alfred Hitchcock’s iconic movie Stage Fright, 1950, heralding his style as the iconic look of the 1950s woman.

Princess Margaret wearing Christian Dior / photo Cecil Beaton / 1951 © Cecil Beaton, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1954 and 1957 Dior released two new fashion lines which were well received, but neither raised the same level of controversy, notoriety or success as his first “New Look.” Nonetheless, he was able to tap in to the commercial market in the United States, establishing a ready-to-wear fashion house in 1958 on the corner of 5th avenue and 57th street in New York. In the same year, Dior launched his first perfume line, Miss Dior, in homage to the tenacity of his younger sister, who had been imprisoned and released from a concentration camp during the war. Dior raised further controversy after launching a series of luxury accessories including furs, stockings and ties emblazoned with his design logo, a fashion first. In response, the French Chamber of Couture came down heavily on Dior, accusing him of “cheapening” the haute couture industry, but in the next decade or so Dior’s example would be followed by the majority of Paris’ fashion houses.

By the mid-1950s, Dior’s business had become a much-respected empire, prompting him to hire the 21-year-old Yves Saint-Laurent as his right-hand man to aid with ever-expanding demands. But in 1957, the same year that his face appeared on the cover of TIME magazine, Dior died suddenly from a heart-attack at the age of 52. His untimely death took the fashion world by shock, leaving one of the world’s most established new fashion houses rudderless.

Saint-Laurent was the obvious successor as artistic director, particularly since Dior had hand chosen him. In the past few decades, prominent voices that have taken up the helm include Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferre, John Galliano, Bill Gaytten and most recently, Raf Simon, who have all injected the fashion house with new forms of luxury and decadence, maintaining the brand’s status today as a multi-million-pound business, and one of the world’s best known fashion lines. Countless designers have followed Dior’s post-war emphasis on extravagance, decadence and femininity, including Thom Brown, Miuccia Prada, and Vivienne Westwood, each stretching Dior’s pioneering, unashamedly feminine, decadent “New Look” in progressive, fashion-forward directions for a new generation. Summing up the strength of his legacy, Dior wrote, “Real luxury requires real materials and a genuine craftsmanship.”

3 Comments

Pingback:

The Top 10 Luxury Designer Brands You Need to Know - Luxury Replica StorePingback:

What is Women's Fashion? | Poor Pretty DollPingback:

Fashion Trends From Around The Globe: Identifying The Most Influential Country