Caroline Walker: The Female Gaze

“I’m often thinking about how paintings position you as a viewer.”

Caroline Walker’s enigmatic, quietly unnerving paintings hint at silent narratives without giving away the game. Women are her subjects, seen from afar in modern houses, nail bars, hotels or hospital beds, as we become passive voyeurs into their daily lives. Much like the 20th century, Parisian male flaneur who wandered the streets of Paris, Walker’s paintings observe without judgement the complex lives of women today, inviting us, as viewers, to question our prejudices and assumptions. Like many women painters of her generation, Walker’s female gaze breaks apart the traditional male view that has dominated art history for centuries, opening up a fascinating discussion on how women view each other in daily life, and where the male view fits into this equation. “My work definitely engages with the history of painting women,” she writes, “which has largely cast the male artist as the portrayer of the female realm. I suppose I’m revisiting that, but through a female gaze.”

During her childhood in Dunfermline, Scotland, Walker developed an early infatuation with art, remembering back, “I was mad about drawing and painting from a very early age, and would spend countless hours in my first studio (a large kitchen cupboard I commandeered) drawing endless pictures of women, so I would say it was hard wired from the start.” Her mother often took her on outings to the local Kirkcaldy Museum, where she saw paintings by heavyweight, traditional male artists including the Scottish Colourists, Thomas Gainsborough and 19th century Glasgow Boys, unashamedly confessing, “I still love these paintings now.”

Walker studied painting at Glasgow School of Art from 2000-2004, before heading off in 2007 to study an MA in painting at London’s Royal College of Art. As a student, Walker made figurative paintings based on friends who were willing to model for her, who just happened to be mostly female. Over time, though, they ignited in her a fascination with the portrayal of women, fuelled by Lucy Lippard’s wry observations such as her favourite excerpt, “It is a subtle abyss that separates men’s use of women for sexual titillation from women’s use of women to expose that insult.”

Since graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2009 Walker has remained in London, where she has sustained a prolific and hugely successful career. Based on her own photographs, the subjects for Walker’s paintings often involve a complex, theatrical set up where a venue is hired and filled with props, clothing and hired models, allowing her to build a suspended narrative of her own imagining, a process she likens to a “primitive film shoot”. After taking hundreds of photographs, these are then worked up into drawings and oil sketches before being translated onto canvas, although she often admits the final painting looks entirely different from the original photographs.

Perhaps this is in part because the painterly language Walker employs is not slavishly photorealist, but retains a certain loose, aqueous quality, with an abstract visual appeal. Influences on her loose style come mainly from the early 20th century observations made by Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Walter Sickert, who, as she points out, placed equal importance on style and subject.

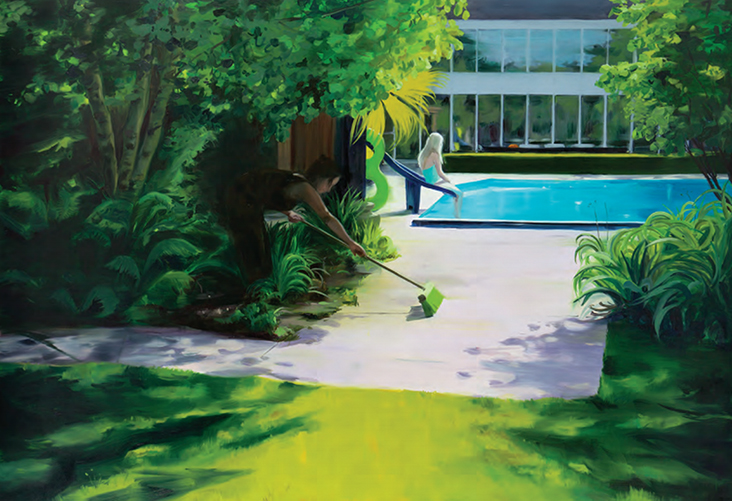

Many of her paintings made before 2010 set women in traditional Victorian houses, but this has more recently shifted to the portrayal of modern, newly built housing. She observes the stereotypical masculine associations that come with the angular designs and clinical austerity of these settings, seen in works such as Illuminations, 2012 and In Every Dream Home, 2013. As much as they present an idealised home environment comparable with David Hockney’s LA swimming pools or Alex Katz’s high society portraits, there is also an uneasy quality of observing women contained within the domestic sphere, prompting some critics to accuse Walker of perpetuating an oppressive view. But as Walker has pointed out, why do viewers immediately assume the women are being contained, when perhaps they are the owners of their own homes?

Other works are more overtly sexual and confrontational, including Conservation, 2010 Ward Round I, 2012 and Ward Round II, 2012, images which observe nude women who are unaware of being watched, placing them in a vulnerable position. Walker remembers a discussion with a male journalist who was surprised these paintings were made by a woman. “I’m interested in whether the knowledge that something has been painted by a woman might change the way you feel about what you are looking at,” she argues, “or challenge your assumptions about a relationship between artist and model.” How might women look at these images in contrast with men? The response is hugely individual, but Walker has observed, on at least some level, how women identify with her figures: “They see themselves in those positions, whereas, I suppose, men are approaching it more objectively, as an onlooker.”

Since 2016 Walker’s practice has shifted from mock-theatrics towards the documentation of real lives, particularly those of women around her in London. Her ‘Nail Bar’ series, including the work Pampered Pedis, 2016, began in response to the proliferation of nail salons she walked past every day, observing with fascination places run exclusively by, and for, women, and the sense of social belonging and camaraderie that surrounds them, commenting, “I’m interested in .. the relationship between women, or how women perpetuate their own position in a patriarchal society.” But undoubtedly these paintings ask questions about women’s relationship with the beauty industry today, and the pressures they face to conform to a certain ideal, particularly when there are more treatments available than ever before. Walker invites us to consider whose ideals they are trying to conform to, and whether the desire to look a certain way is driven by internal or external pressures, questions which are complex and difficult to answer.

While Walker has occasionally been criticised for producing images that aren’t empowering for women, she is quick to point out it is not her intention to empower or disempower, but to simply observe and ask questions, arguing, “I find it interesting that there might be this assumption that, as a woman, it is somehow my role to represent women in a way that should be empowering.” Perhaps it is telling that much of the criticism levelled at her work has come from men, who may find, at times, their preconceived ideas being challenged by her uncompromising imagery.

Walker was recently commissioned by Kettle’s Yard to paint a series based on London’s refugee women as they flit between one transient accommodation and another. After following and documenting the lives of five different women, Walker dedicated a painting to each of them set in an interior scene, like much of her previous works. But the acute, painful sensitivity of the subject matter marked a departure in Walker’s practice, moving beyond the polished sheen of luxury homes and beauty bars towards the more intimate and human side of real women’s lives. Seeing their belongings tied up in bundles or shoved into bags around them conjures up the many struggles of a homeless life, but Walker hopes her paintings will come to raise awareness of her heroines’ plight and even become a conduit for social change, explaining, “It’s my hope that the work will look at notions of home for women in this situation.”

Since producing this series, Walker’s work has continued with a social realist slant. Since 2018 she has focussed on the many silent roles traditionally associates with, and still dominated by women, including seamstresses, kitchen porters, chambermaids and cleaners, roles that allow workers to become invisible and unrecognised. Connecting with and raising awareness of these unsung heroes recalls the feminine language of Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, who similarly captured women in the domestic sphere, not as submissive and compliant, but determined and strong. Walker’s paintings can be read as modern day Impressionist scenes, capturing without judgement the many roles of femininity today as seen through the eyes of a fellow female traveller, navigating her way as best she can. The disquieting unease she skilfully invests into her ordinary scenes through dramatic lighting and vivid colour lend her scenes a deeper intellectual complexity, while just hinting, with discreet language, that all is not well. She writes, “My favourite paintings tell me something about the culture, society and political times they were made in, but in a subtle way.”

Feature image: On the Board / Caroline Walker / 2019

2 Comments

Sarah Dombrowsky

Thank you for introducing me to yet another artist whose work makes my heart and brain sing together.

It’s so generous of you, Ms. Lesso, and of the Fabric Store, to add this component to the site.

Vicki Lang

Thank you for giving such a wonderful insight to another painters world. Love her works. Being a cosmetologist myself I love the Cut and Finish painting.