Natalia Goncharova: The Spirit of Russia

“A spark of the spirit lives in us, it is connected with all spirit. It is divine. It is drawn to other, similar sparks. This is the urge to creation.”

Natalia Goncharova was an explosive force of creativity, encapsulating the wild spirit of avant-garde Russia with painting, printmaking, performance and design. Throughout her long, prolific career she produced some of the most revolutionary works in the history of art – today her work has become the most valuable of any female artist, even outselling Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo. Though she leapt across styles and techniques, there was a deeply spiritual thread running through all her art, one which united iconography from her native Russia’s rich art history with Western avant-garde abstraction. On bringing her distinctively Russian art to Europe in the early 20th century she wrote, “I am reopening the way to the East, and I am sure, others will follow it.”

Born in the town of Negaevo in the Tula Province of Russia, Goncharova came from a distinguished family of landowners. She was named after her great aunt, Natalia Pushkin, wife of the monumental Russian writer Aleksandr Pushkin. On her grandmother’s family estate Goncharova developed a lifelong appreciation of simple, rural life, where she witnessed people living and working in close harmony with the land. For the rest of her life she linked her identity back to this strand of her childhood, referring to herself fondly as a “country girl.” With her much loved grandmother she regularly attended church, observing with curious fascination the weight and gravitas religious icons could hold. After suffering series of financial strains, Goncharova’s father moved his family to Moscow in 1891 when she was 10 years old.

As a young art student at the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Goncharova met and fell in love with fellow student Mikhail Larionov, forming a creative and mutually supportive partnership that would last a lifetime. Goncharova observed, “Larionov is my conscience in my work, my tuning-fork. We are very different, and he sees me from inside of me, not of him. Like I see him.” Though she had begun studying sculpture, Larionov persuaded her to switch to painting, encouraging her natural sensitivity to colour.

In 1903, while still a student, Goncharova visited the Crimea with Larionov, where she first began developing Impressionistic paintings exploring the flickering patterns of natural light. Back in Moscow Goncharova and Larionov became part of a thriving art scene, where they befriended various influential figures including art critic and patron Sergei Diaghilev, who persuaded them to exhibit their work in several European exhibitions. When Goncharova’s paintings were included in Moscow’s Golden Fleece exhibition 1908 she encountered the rebellious and outlandish painting styles of Post-Impressionism and Fauvism. Such progressive art was frowned upon by the Russian art establishment, but Goncharova was hooked. In the following year she was expelled from the Moscow Institute for failing to pay her tuition fees, but she was already integrating herself with a thriving art scene which would lay the foundation for her future career.

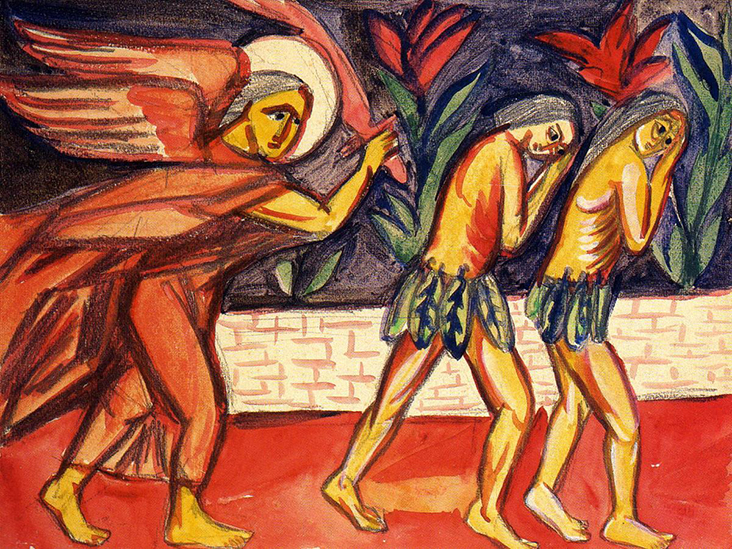

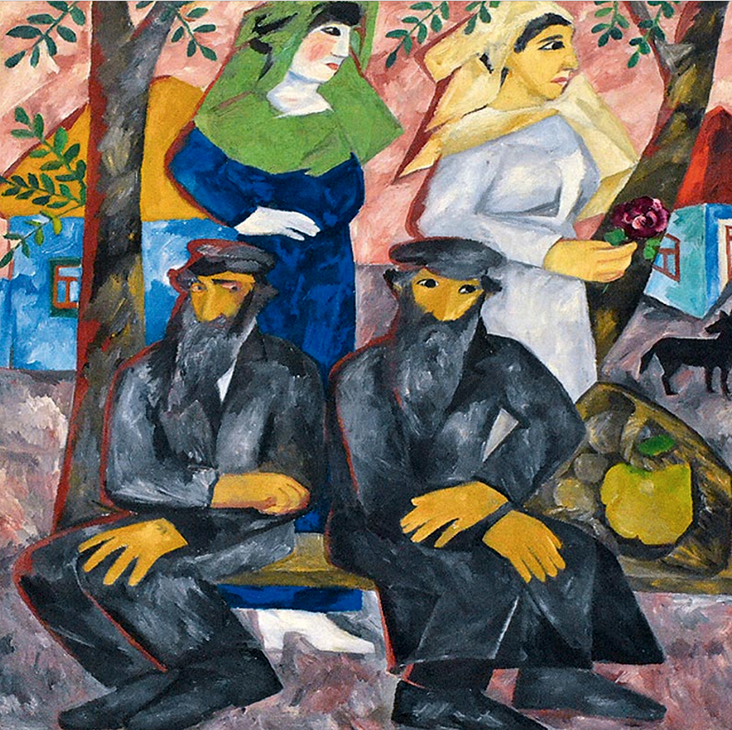

By 1910 Goncharova had begun working in a Neo-primitive style, blending Cubist and Fauvist styles of painting and printmaking with the traditional, stylised motifs of Russian lubok posters and Byzantine icons, as seen in her sympathetic portrayals of peasants, workers and Jewish figures. Larionov joined her on this mission and the pair explored a distinctly Russian style of modern art that would come to rival their European contemporaries. In the same year, Goncharova and Larionov founded the revolutionary artist group the “Jack of Diamonds”, moulding themselves into Russia’s leading avant-garde. The deliberately subversive name for their group made reference to the playing card character known as a rascal, or rogue, drawing attention to the irreverent, rebellious nature of their practices. Like Goncharova, many of the group’s members had been expelled from the Moscow Institute, some for simply painting in the Post-Impressionist style.

For the group’s first exhibition catalogue cover in 1911 Goncharova designed a woodblock print representing the Archangel Michael as one of the horsemen of the Apocalypse, reflected the group’s mission to bring about the death of the establishment and the birth of a new cultural and spiritual change. What initially began as an exhibition society for Russian artists soon expanded to include works by the world’s leading creatives such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Wassily Kandinsky, Andre Derain and Henri Matisse.

In 1910 Goncharova held her first solo exhibition in Moscow, which attracted vitriolic criticism for its experimental techniques and non-traditional subjects. Two of her female nudes were referred to as “disgusting depravation”; after being confiscated by the police Goncharova was charged with indecency, but later acquitted. Goncharova was undeterred – in 1911 she spread her wings further, exhibiting with Germany’s radical collective Der Blaue Reiter, sharing with the group a fascination with crude, expressive painting styles and heightened, artificial colours.

Fractures were gradually appearing within the Jack of Diamonds collective, with some members favouring Russian styles and others Western art. Both Goncharova and Larionov led the Russian strand away into a new group called the “Donkey’s Tail” in 1912. In this new collective Goncharova mainly exhibited paintings based on Russian icons from the Orthodox Church, tapping in to her fascination with art as a gateway into the spiritual world. Yet her contemporary take on religious paintings was heavily criticised by the church, while her lifestyle choices further angered traditional establishments; she lived unmarried with Larionov, wore men’s clothes, and with Larionov walked the streets topless painted with body and face art. Writer John Bowlt reflected on the ways her persona influenced the reception of her art: “Goncharova enjoyed a licence that only actresses and gypsies were permitted, and perhaps because of this dubious social reputation rather than as the result of any apparent innuendoes in her paintings, she was said to traverse the boundaries of decency and to ‘hurt your eyes.’”

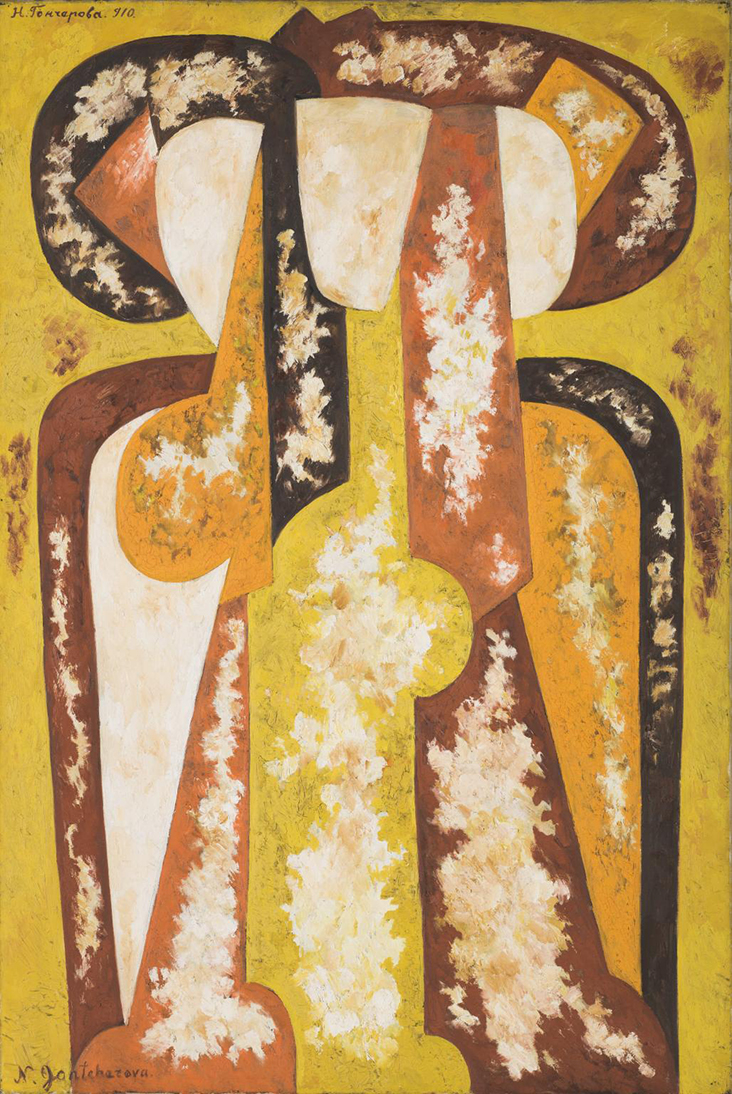

As influenced by the rising trend for Futurism, Goncharova and Larionov spearheaded a new style of painting called Rayonism, which deconstructed rays of light fractured off objects in space. Enlisting a band of followers, they wrote a manifesto in 1913, describing their style as “a sum of rays proceeding from a source of light – these are reflected from the object and enter our field of vision.” In these paintings Goncharova came closer to abstraction than ever before, aiming to represent the immaterial world just beyond the human eye, or in the “fourth dimension.”

Goncharova’s Rayonist paintings brought together an encyclopaedic range of subjects, collapsing together multiple ideas in a practice she referred to as ‘everythingism’, aimed at capturing the frenetic pace of modern, industrialised Russian life. One of her recurring themes was the abstracted forest, acting as a passageway from the real into the metaphysical world, as seen in La Foret, (The Forest), 1913, in which, as writer Tim Harte puts it, “…a primordial spirit permeates the natural landscape.”

In 1913 Goncharova also organised an epic retrospective exhibition in Moscow, featuring over 800 of her artworks from the past ten years, revealing what a prolific and inventive artist she had become. She was the first member of the Russian avant-garde to take on such an ambitious project and though public reactions were divided the show attracted a huge crowd, cementing her reputation as one of the country’s most radical artists.

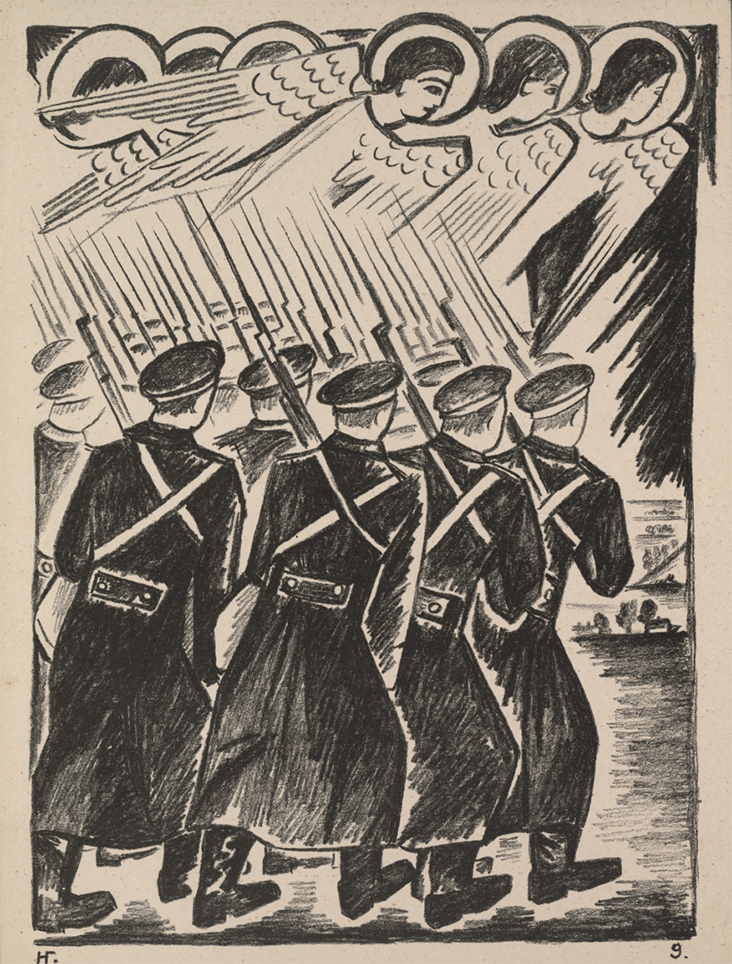

Alongside her Rayonist paintings Goncharova collaborated with several writers who had joined the ever expanding Donkey’s Tail group. Projects included the creation of delicate lithography illustrations for Sergei Bobrov’s poetry in Gardeners over the Vines, 1913 and in 1914, a response to the outbreak of war in Russia with the powerful and moving portfolio of patriotic lithographs Images of War, 1914.

Khristolyubivoe voinstvo (Christian Host) from Misticheskie obrazy voiny. 14 litografii (Mystical Images of War: Fourteen Lithographs) / 1914

Goncharova and Larionov moved to Paris in 1914, where their close friend Diaghilev had founded his widely acclaimed Ballet Russes; he encouraged both artists to design sets and costumes for his theatre productions to gain a secure income. In the years that followed Goncharova became primarily recognised as a stage and costume designer, working with Diaghilev for the next 15 years and travelling widely around Europe with his troupe. Her eye catching designs incorporated elements of traditional Russian art, contributing greatly to the success of his theatrical productions.

Leonid Myasin, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Igor Stravinsky (sitting down), Léon Bakst / 1915

Throughout her travels she was particularly drawn to Spain, where the country’s patterns and colours had a profound influence on her design work, writing “I love Spain. It seems to me out of all the countries I have visited, this is the only one where there is some hidden energy. It is very close to Russia.” When the Russian Revolution struck in 1917 Goncharova and Larionov were forced to relocate permanently to Paris, though she missed her home country deeply. Work with the fashion house Mybor in the 1920s gave her room to reminisce back to her native, beloved Russia, with designs featuring the patterns and colours of Russian folk art.

While the later part of her career was dominated by stage and fashion design, Goncharova never gave up her practice as a painter, continuing to discover ideas that would inform her design work, writing in a letter to a friend, “…painting is an inner necessity for theatre design, not the other way around.” After settling in Paris her paintings became increasingly abstract, while in her later years she continued to depict realms just beyond our grasp with her ‘Space’ series, made after the launch of the Sputnik satellite.

Since her death in 1962 art history has tended to enmesh Goncharova’s legacy with that of her partner Larionov, who died two years later. They undoubtedly worked intimately together, crossing ideas back and forth in an ongoing creative interchange, but some historians have wrongly suggested Larionov was Goncharova’s mentor, rather than her equal. In recent decades various major showcases have disentangled Goncharova’s work from Larionov’s in order to celebrate her legacy in its own right, revealing the ways she tapped into art’s ancient spiritual properties with a distinctly Russian voice, and merged it with Western Modernism. Such ideas fed through into the practices of countless artists to follow, such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, while contemporary Russian, female artists who follow in her footsteps include Sasha Pirogova, Irina Taus Makhacheva and Isis Irina Korina.

Natalia Goncharova Theatre costume for the Coq d’Or in the Ballets Russes production of ‘Le Coq d’Or’ (The Golden Cockerel) / 1937

Later this year Tate Modern will house Goncharova’s first ever UK retrospective, revealing the breath-taking scope of her hugely varied career. Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva summed up her legacy: “She has the courage of a Mother Superior. A directness of features and views. Such is Goncharova, with her modernity, her innovation, her success, her fame, her glory, her fashion… To sum her up? In short: talent and hard work.”

3 Comments

Rita Cleland

I love this tutorial on Natalia Goncharova. So full of life! And strength! I had hoped you would offer the first print as a fabric. I did not see the others, but I will read them now. What a brilliant idea to offer these stories and prints on your website: people who love fabric love art. Thank you so much. — marilyn cleland

Peggi Laubenheim

Thank you for some very interesting articles to educate and enlighten. We can all use some more!

I wish I needed more linen as you have a great selection. This summer I’m for sure going to get some curtains made.

Vicki Lang

thank you so much for your artist series. You have brought to light so many artists. I especially love your female artist series.