Hannah Hoch: Rebel with a Cause

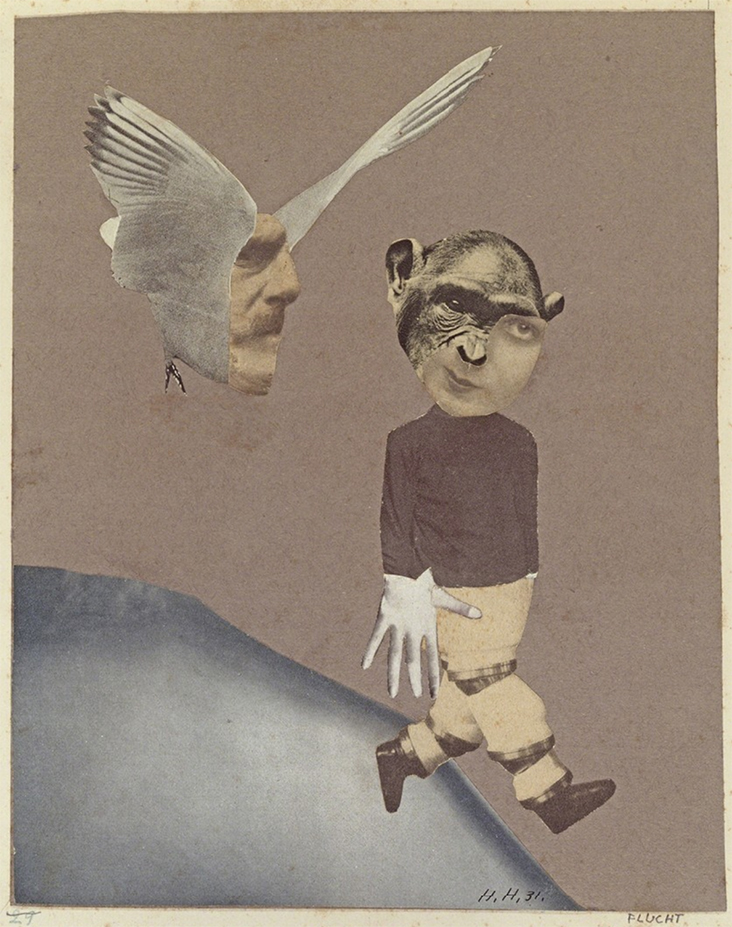

In Hannah Hoch’s collage wonderland anything is possible; men’s faces sprout wings and chase primeval monsters, broken artefacts assemble into beasts and women’s bodies are cut apart and left to float in space. She wrote: “…there are no limits to the materials available for pictorial collages – above all they can be found in photography, but also in writing and printed matter, even in waste products.” There is a richly layered, dense materiality in her work, but more importantly Hoch’s knack for pulling apart this once familiar fabric of daily life and rendering it incomprehensible, darkly humorous, satirical and even dangerous reveals her truly anarchic, rebellious spirit at play.

As the only female artist associated with the pioneering Dada group in Germany Hoch was a trailblazer, combining revolutionary photomontage techniques with politically subversive content. Much like her male peers Hoch was sceptical of postwar, Weimer Germany as it came apart at the seams, but into their macho world of bravado and exhibitionism Hoch brought a sensitive and sharp feminist eye, producing acerbic, biting images that addressed with brutal honesty the inequalities women were facing. Her work pre-empted many of the art movements that followed her, where appropriated imagery became a popular choice for artists wishing to shake up and critique the mediated world around them.

Born in 1889 in Thuringia as Anna Therese Johanne Hoch, Hannah was raised in an upper-middle class household. As an adolescent her father believed, as she put it, “a girl should get married and forget about studying art.” At 15 she left school to take care of her younger sister, but her education resumed in 1912 when she began studying glass design at the Berlin School of Applied Arts. At the outbreak of war the school was closed and Hoch joined the Red Cross for a year, before taking up a degree in graphic design at the School of the Royal Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin. Years later, as an artist, Hoch admitted she had been too nervous to apply to the male dominated industry of fine art, choosing instead to focus on design, a subject deemed more suitable for “women’s work.”

During this time the artist added an ‘H’ to the front of her name, changing it from Anna to Hannah, deliberately making it palindromic. Hoch also met and began a tempestuous relationship with the Dada artist Raoul Hausmann who would introduce her to the wider Dada group in Berlin’s underground art scene. After graduating Hoch took up commercial work for the publisher Ullstein Verlag, designing unique patterns for crochet, knitting and embroidery. At a time when artists and designers were increasingly overlapping their practices, Hoch was a strong advocate for the powerful societal role handcrafts and textiles played. She even wrote a manifesto style statement in support of modern embroidery, encouraging Weimar women to integrate aspects of Modernist design into their practice, in order to “develop a feeling for abstract forms.” She wrote, “Embroidery is very closely related to painting. It is constantly changing, with every new style each epoch brings. It is an art and ought to be treated like one…”

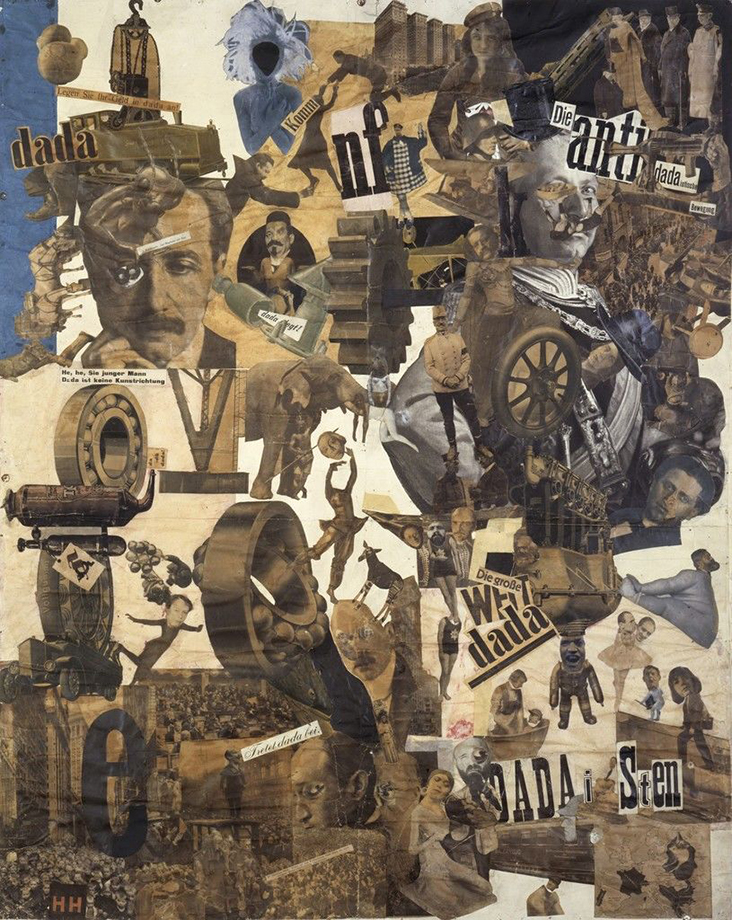

Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany / Hannah Hoch / 1919 / Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

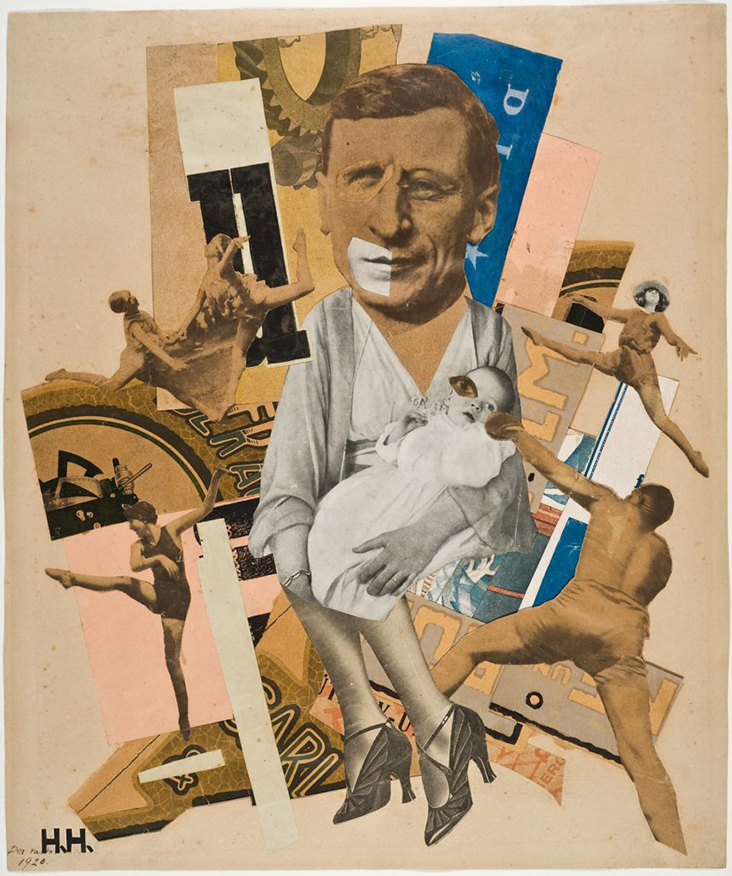

Hoch spent a decade working in the design industry, but all the while she was developing photomontage techniques, lifting material from popular culture and dismembering it into unsettling or haunting arrangements. Such imagery should have made her an ideal member of the male-centric Berlin Dada group, but despite attempts to integrate with them at their regular evening soirees she was frequently met with disdain and disregard. Dada member Hans Richter described her in patronising terms as a “good girl” with a “slightly nun-like grace,” referencing her in his memoir as the group’s glorified waitress, bringing, “…sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money.” In 1920 when Hoch submitted work for the First International Dada Fair, Grosz and Heartfield tried to edge her out of the frame by having her work removed, but when Hausmann, a leading member of the group, threatened to withdraw his own offerings if they failed to include her, they relented and allowed her in.

Hoch’s retaliation revealed great tenacity; along with a series of smaller photomontages and her trademark sculptures of Dada Dolls, she also exhibited her ground-breaking and now world famous metre wide collage, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1920. The work is a searing satire in which women battle with men and political leaders, while a map shows the few European countries where women could then vote; despite their best efforts to squeeze her out, Hoch’s work rose as one of the show’s greatest hits.

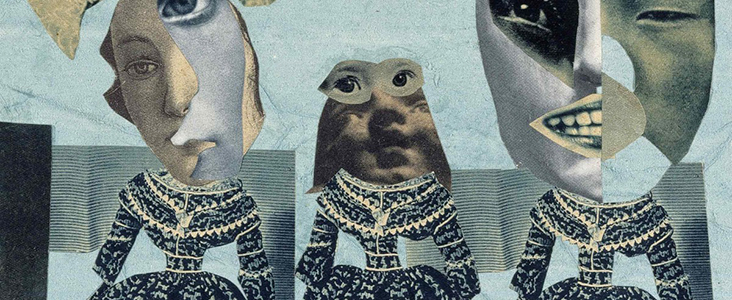

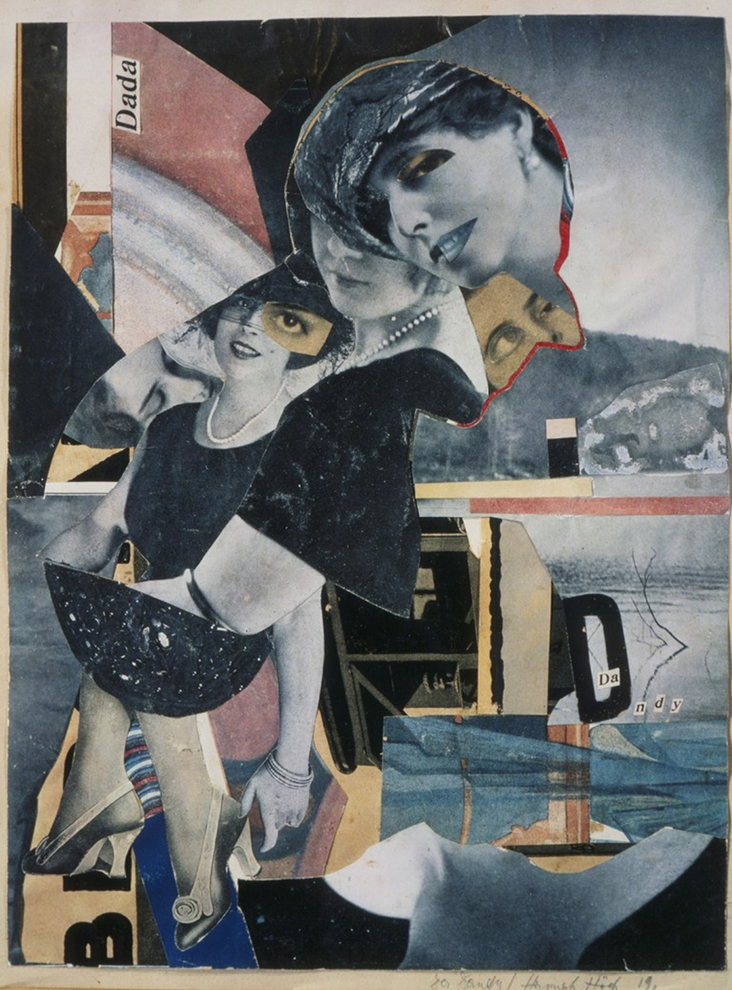

In many of Hoch’s Dadaist photomontages she addressed the blatant inequalities women were facing in Weimar Germany; in Dada-Ernst, 1920-21 for example she pulls apart public attitudes towards women as sex symbols by fracturing their contours. Though the notion of the ‘New Woman’ was an increasingly popular term to describe rising numbers of independent, self-sufficient women, Hoch rightly pointed out the inability many men still had to accept them as true equals. She wrote, “None of these men were satisfied with just an ordinary woman. But neither were they included to abandon the (conventional) male/masculine morality towards the woman. Enlightened by Freud, in protest against the older generation … they all desired this ‘New Woman’ and her ground-breaking will to freedom. But – they more or less brutally rejected the notion that they, too, had to adopt new attitudes … This led to these truly Strindbergian dramas that typified the private lives of these men.”

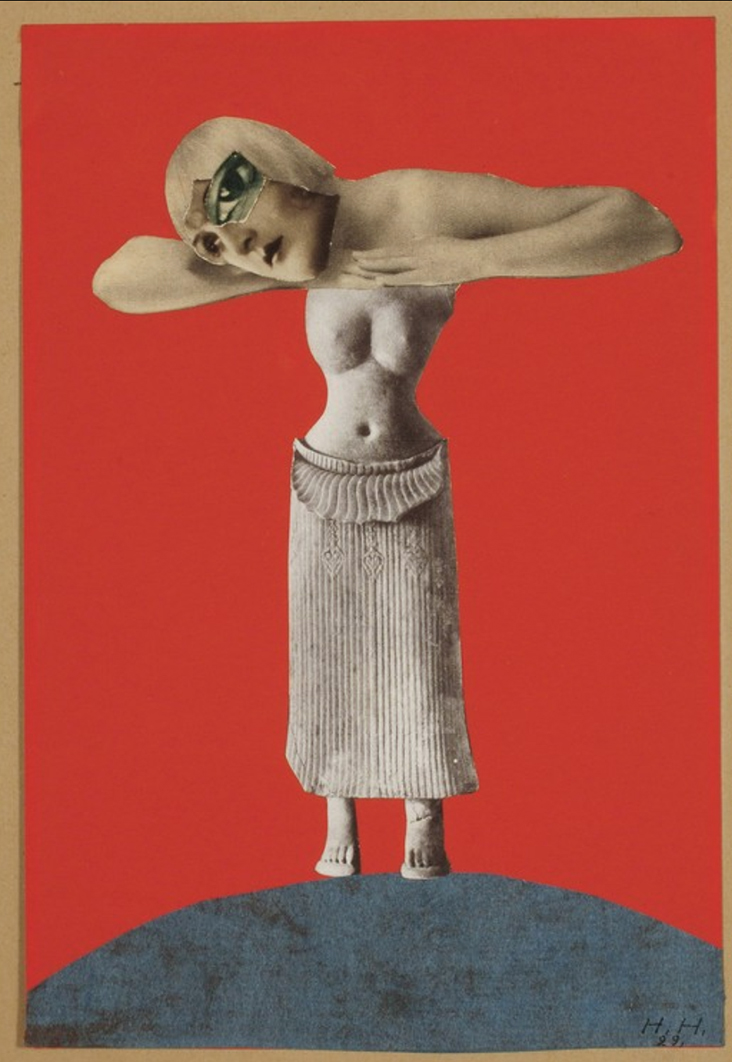

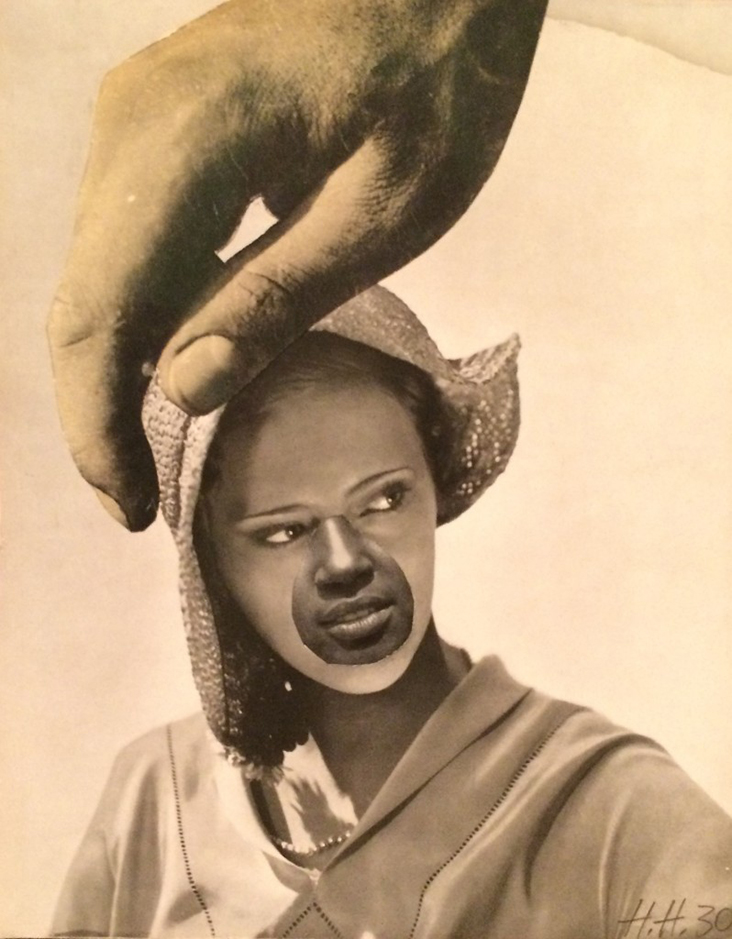

Indian Dancer: From an Ethnographic Museum (Indische Tänzerin: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum) / Hannah Hoch / 1930

By 1922 Hoch and Hausmann’s relationship had dissolved. Hoch was growing increasingly tired of the posturing and exhibitionism the male Dadaists promoted and by the end of the decade she had left the group behind and moved to The Hague in the Netherlands in search of a fresh start. There she was greatly influenced by the Dutch De Stijl movement, with its focus on pure colours and simple geometry, befriending Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. In The Hague Hoch developed a relationship with the female writer Til Brugman, who she would remain with for the next 10 years.

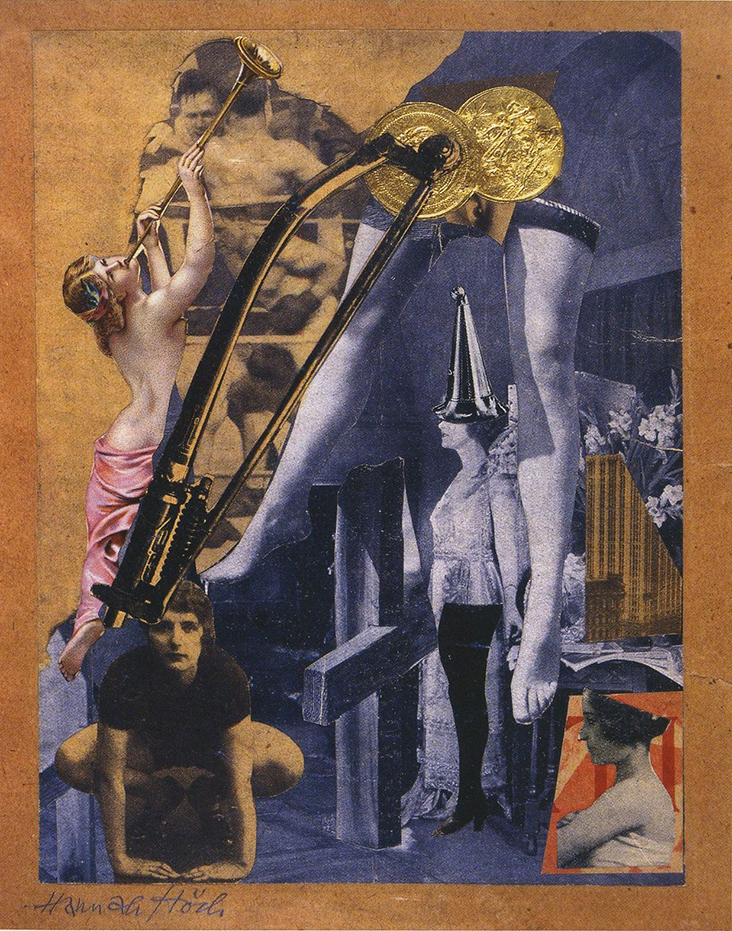

Though she mostly exhibited paintings during her Dutch period, she made some of her most profound photomontages in private which would come to the fore years later. These include the series From an Ethnographic Museum, a group of 17 collages made in the late 1920s which combined images of museum artefacts, such as tribal masks and stone carvings, with parts of women’s bodies and faces, along with elements of De Stijl style geometry. On the one hand this series was a commentary on the ways men idealise and objectify women’s bodies into museum-like ornaments, but her strange hybrid creatures also have a youthful, child-like quality, pointing out the patronising and infantilising treatment women so often had to face.

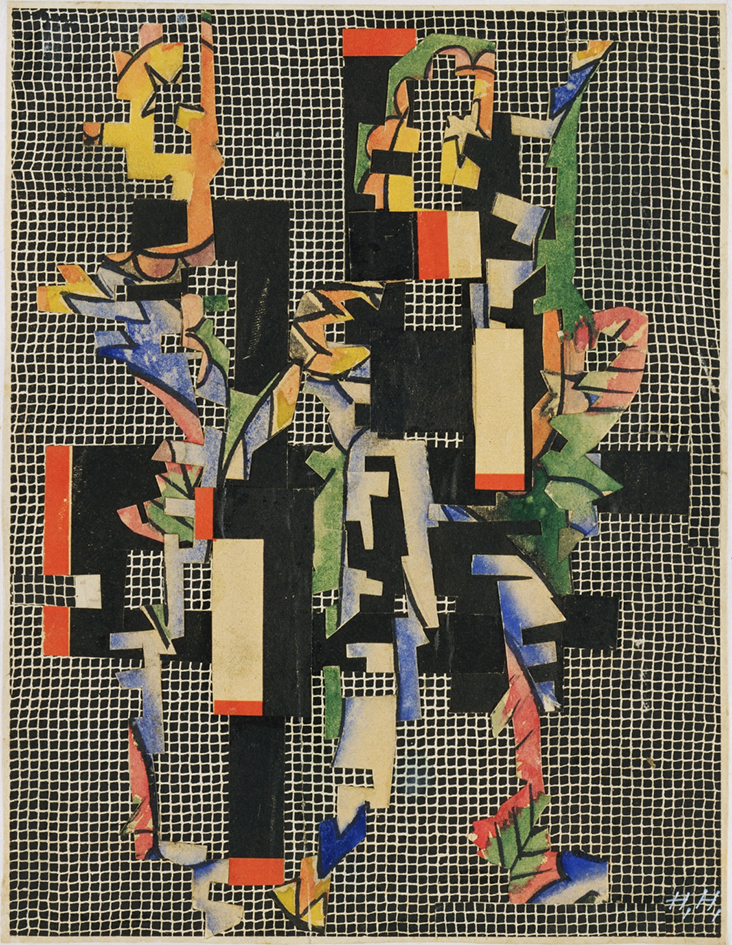

Collage II (On Filet Ground) (Collage II [Auf Filetgrund]) / Hannah Hoch / c. 1925 / Cut-and-pasted printed and painted paper on printed paper

Like many early 20th century avant-gardists Hoch’s practice suffered greatly as a consequence of Nazi rule. An exhibition combining both her photomontages and paintings at the Bauhaus in Dessau was cancelled in 1932 when the Nazi party forced the school to close, while along with many of her peers she was labelled a maker of “degenerate art” and a “cultural Bolshevic.” Hoch returned to live in Germany in 1936 following the breakdown of her relationship with Tillman, buying a house near Berlin and later marrying the businessman and pianist Kurt Matthies in 1938. But she was forced to go into hiding throughout the Second World War, writing, “I had to disappear as completely as if I lived underground.” Living in fear that her neighbours would find her out and turn her in to the Nazis, she kept all her artwork and the works she owned by her friends hidden away in a cabinet. As her fellow artists fled Germany or were deported to the camps she was struck by “a great loneliness” that would haunt her for years as she remained in isolation.

After the end of the war Hoch described an immense sense of relief, writing, “In my soul there is a calmness, such as I haven’t felt for many years.” She gradually began to make photomontages again, embracing the rising trend for abstraction with works such as Industrial Landscape, 1967, where complex, layered shards interrupt and overlap one another in a lyrical display of energy and life.

Although some writers have claimed her work fell out of favour in her later years, closer inspection reveals this not to be the case. While she did continue to live in relative obscurity in her country cottage, her work was exhibited to great critical acclaim throughout the late 1960s and 1970s; she took part in Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1968 and held major solo shows at the Musee D’Art Moderne de la Ville in Paris and the Berlin Nationalgalerie in 1976. Various retrospectives since then have been held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1997, the Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2004 and the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 2014.

Hoch’s astute awareness that the media could become a new, fertile playground for creatives preceded the language of Surrealism, Punk, Pop Art and Postmodernism, making her a pioneer that was way ahead of her time. But more importantly, her blatant attacks on systems of misogyny revealed just how vital it is that women comment on the images that attempt to define them. Various female Surrealists, including Claude Cahun and Grete Sterne continued to expand these ideas, while in a more contemporary context her legacy is keenly felt in Linder Sterling’s radical feminist photomontage and Cathy Wilkes’ theatrical setups. On defining herself as a woman, artist and creative thinker, Hoch wrote, “I wish to blur the firm boundaries which we …tend to delineate around all we can achieve.”

6 Comments

Cilla Walford

Hoch’s quiet courage combatting the patriarchy of the Dada art movement is inspiring. Beautiful, powerful images. Thank you so much for your insightful, informative, and erudite essays, Rosie. I always look forward to reading them.

Sue Carney

Are you kidding me…This is pure nihilistic boredom. Want to be a rebel. Get married,have kids, be happy. That is rebellion in this culture.

Susan Ray

Obviously , written in your opinion…..some people have different inner-workings than you…..as difficult as it was for a female artist…..Hoch’s voice shared with us is invaluable.

Taryn Yamane

Thank you for bringing Hannah Hoch’s life and work to the forefront of our awareness Rosie. Despite my love of art, I had not heard of her until today. I am very much struck by not only the beauty, but the timeless relevance and sharp commentary captured in her work.

Your articles on art history are insightful and well-written. I am particularly enjoying your writings on the significant contributions of women in art – a recognition long overdue. It is inspiring to read of women who remained true to their calling, in spite of the marginalized place of women in the art world, and society in general, at that time. Please keep up your thoughtful and intelligent sharing!

Dorann Kelley

Thanks so much for sharing this! I have been contemplating my life and realizing, not unlike Hoch’s work, it is a montage of events and experiences. Reading about her has helped me to realize one can create significance and beauty out of the disjointed pieces of life.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you both for the positive feedback – that’s great to hear you are enjoying our new series on women!