Lifting the Veil: Women who Shaped Art History

“The macho art world has ignored the contribution of women. But we have the power to change this.” [1]

Art history can be a tricky, slippery construct to build; the broad frameworks we so often see sketched out in major publications or art museums rarely give us the whole picture. Many vital, influential figures throughout the history of art have been side-lined, forgotten or lost through time. A large number of those lost voices have come from women, who have faced prejudice, criticism and marginalisation for centuries in the hands of a male dominated industry. In this new series, we will delve into the lives and works of some of the most influential female artists throughout art history, celebrating their careers and influences, while exploring the struggles and adversities they faced, and often tackled head on with courage under fire.

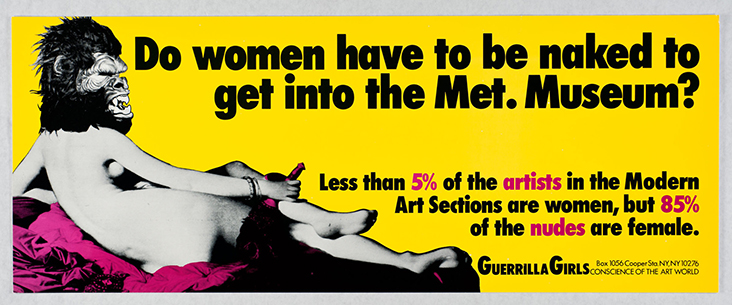

In 1985 New York’s all female, gorilla mask wearing artist group The Guerrilla Girls began a feminist campaign aimed at addressing the endemic sexism and racism in museums across the Western world. Together they published a series of posters with attention grabbing headlines, including, most famously, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.” Since this time, some institutions are more willing to address issues of inequality today than others – Tate Modern ranks highest for its representation of women artists, but is still predominantly male dominated. One of the reasons for this discrimination is linked to the art market, which continues to place greater monetary value on work by male artists than their female counterparts.

But the root of the problem lies deeper; back in 1971, writer Linda Nochlin argued in her radical feminist article, Why Have there Been no Great Women Artists?, that this under-representation of women in the history of art is an ingrained social concern, where women have been consistently denied the same privileges as men, writing, “…the total situation of art making, both in terms of the development of the art maker and in the nature and quality of the art itself, occur in a social situation, are integral elements of this social structure, and are mediated and determined by specific and definable social institutions, be they art academics, (or) systems of patronage …”

Nearly 40 years later, the Guerrilla Girls put the problem out there for academics and institutions to address, asking not, “Why haven’t there been more great women artists through Western history?”, but, “Why haven’t more women been considered great artists through Western history?” This is the issue at the forefront of several institutions today as society revisits a new wave of feminism. As women are being allocated more senior curatorial positions they are finally being given room to take the lead and stand up for women’s rights in major institutions, so the trickle-down effect is slowly being felt.

Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern dedicated half of the solo-artist rooms in the 2016 extension, Switch House, to women including Louise Bourgeois and Ana Lupas. She explains, “We didn’t dress it up as a strategy or positive discrimination – it was just great work by women and an attempt to redress the gender balance.” Morris has also supported a number of solo exhibitions at Tate by prominent female artists including Marlene Dumas, Yayoi Kusama, Sonia Delaunay and Agnes Martin, who, irrespective of market prices, are finally gaining greater recognition for their outstanding practices and the powerful influences they have exerted on contemporary art.

Infinity Mirrored Room –The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away / Yayoi Kusama / 2013 / Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York. © Yayoi Kusama

Iwona Blazwick, director of Whitechapel in London adds to the debate, “Until the mid-20th century, the very notion of creativity was designated as masculine, so female artists have had to overcome millennia of being dismissed, neglected or silenced.” Yet, she adds, “What is remarkable is their tenacity and invention.”

Various curators in major museums today, both male and female, are finally embracing the need for greater inclusivity. Some have celebrated women’s vital role in the paradigm shifting period of the early 20th century, which was overshadowed and written out after the destruction of the war. Patricia Allmer’s fascinating anthology, Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism at Manchester Art Gallery in 2009 paid due to trailblazing revolutionaries including Francesca Woodman, Eileen Agar and Claude Cahun, who, as writer Jeanette Winterson points out, “… have made it possible for the women artists that we know now of our generation to get the kind of recognition … the true status that they ought to have.” At the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Modern Scottish Women in 2015 was an embarrassingly long overdue homage to 45 different 20th century female pioneers including Gwen John, Dorothy Johnstone, Joan Eardley and Wilhelmina Barnes Graham.

In a more contemporary context, a huge tidal shift has begun in recent years, as Artsy Magazine’s Anna Louie Sussman argues, “Old women have replaced young men as the art world’s darlings,” prompting a new movement referred to today as OWAs (older women artists). Sussman cites examples including Carmen Herrera, who was 89 when she sold her first work and has achieved international status at the age of 102. Lubaina Himid recently took the art world by storm as Britain’s “oldest winner of the Turner Prize” at the age of 63, while radical sculptor Phyllida Barlow sprang onto the international art scene in her later years. Morris writes, “Many great women have suffered from the shadow effect, they have been out of public view until their 60s and 70s. How great that we have discovered (them) now.”

Several institutions today are also finally beginning to recognise a more in depth historical analysis is needed to bring out lost voices from the past. The Uffizi Galleries in Florence claim to be embarking on a long term initiative aimed at redressing historic gender imbalances led by Eike Schmidt (with some help from the Guerilla Girls), bringing Renaissance masterpieces already in their collection from women artists out of the shadows and into the light, including works by Artemesia Gentileschi, Lavinia Fontana and Felicie de Fauveau. In 2017 they celebrated the exquisitely intricate paintings of 16th century artist Plautilla Nelli with a major solo show. In a wider context these are only small glimmers of light, but they do reveal a vitally important shift in the right direction.

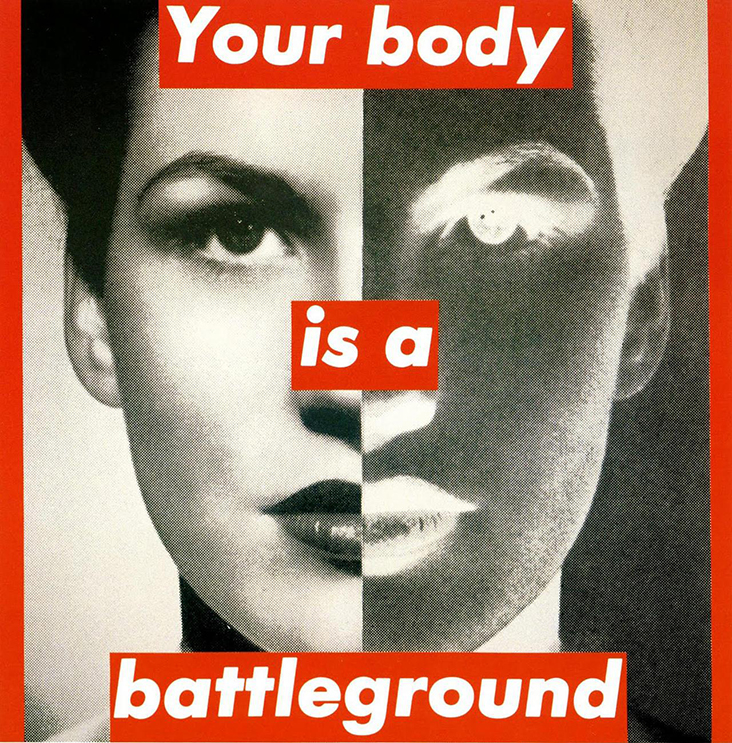

As many writers have pointed out, organisations also need to look at the way women are written about and given recognition in a historical nature; we need to celebrate women artists for their own narratives and achievements, rather than merely tying them to the male figures they associated with. Many women have often addressed these issues directly or indirectly in their practice, either by revealing the tools of oppression and sexism that they have struggled against, or through celebrating their innate strength and power, including Artemesia Gentileschi, Paula Rego, Georgia O’ Keeffe, Jenny Saville, Hannah Hoch, Tamara de Lempicka, Louise Bourgeois, Amy Sherald, Tacita Dean and many more.

Olympia / Jenny Saville / 2013 – 2014 / Charcoal and oil on canvas, © Jenny Saville. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

In a world where more women than ever take on higher education qualifications in the arts and embark on creative careers, it’s time our academic institutions and museums caught up. Connie Butler, chief curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles sees some changes, but not enough, writing, “…if you look at now versus ten years ago, there’s a vast difference in the amount of women artists that you see in the programs of most museum institutions. But then, you look at all of the artists who are in that top echelon of the highest earning artists, whether it’s in the auction world or the commercial world, and there aren’t any women… A cultural shift has to take place.”

Join us next time as we delve into the life and work of pioneering American painter Georgia O’ Keeffe, whose radical paintings played a vital role in establishing American Modernism in the early 20th century.

[1] Judy Chicago, The Guardian, October 2012

Leave a comment