Recreating Aboriginal Traditions: The Textile Art of Emily Kam Kngwarray

Renowned Australian Aboriginal artist Emily Kam Kngwarray (1910-1996) was one of the 20th century’s most remarkable artists, and a current large-scale retrospective at London’s Tate Modern pays homage to the depth and breadth of her legacy. She worked with predominantly with batik, and later acrylic painting on canvas, producing fantastically intricate and brilliantly colourful marks and patterns that are deeply connected to the ceremonies, stories, plants, animals and forces of nature found within her homeland in Australia’s Northern Territory.

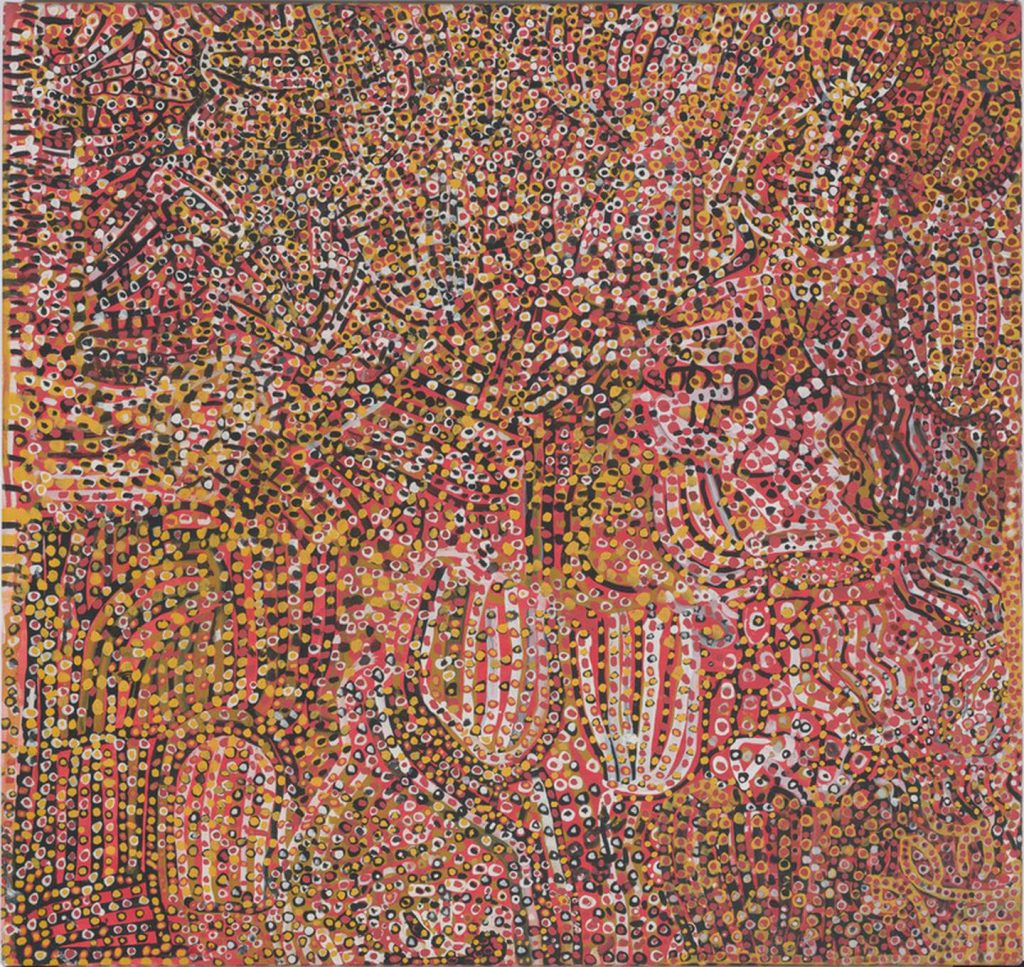

Kngwarray was born in Alhalker, in the Sandover region of Australia’s Northern Territory, and belonged to the Anmatyerr people. The region was her ancestral territory, and she remained here for her entire life. The concept of ‘Dreaming’ was embedded into her cultural heritage, and the belief that ancestral beings known as ‘Dreamings’ were contained within the country’s many abundant natural life forms. As an adult, Kngwarray became a highly respected elder within her community, and a custodian of women’s ‘Dreaming’ ceremonies and sites in the Utopia region of Alhalker. Dreaming ceremonies performed by Alhalker women, known as Awelye, involve painting intricate dotted designs onto their chests and shoulders using ground ochre, coal and ash, along with performing a series of ceremonial chants and dancing that asserted their ownership over the land where they resided.

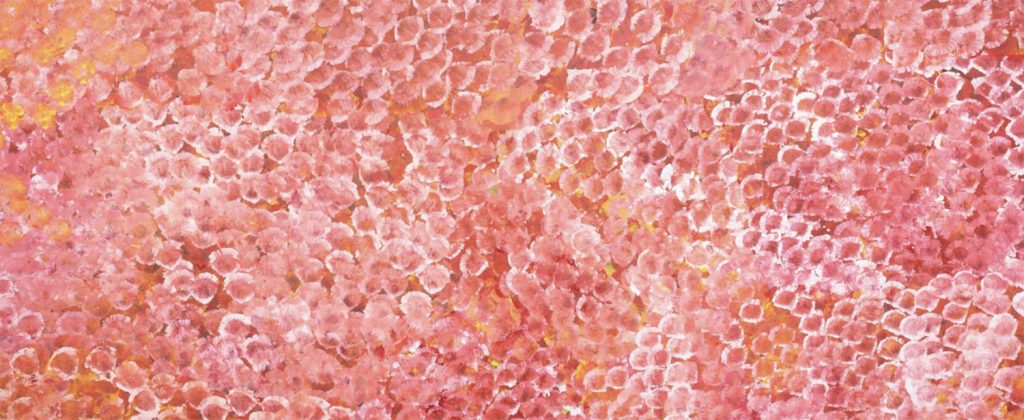

In 1977, a group of Aboriginal women from the Alyawarr and Anmatyerr in the Utopia region were encouraged to form the Utopia Women’s Batik Group in a series of government sponsored workshops; through the programme these women, including Kngwarray, began working with the traditional Indonesian batik process, drawing designs onto silk with hot wax and applying dye, which could then be drawn over with more wax and made more complex with new layers of colour. We see in Kngwarray’s batik fabric designs how she incorporated the ‘dot by dot’ appearance of Awelye body painting into her richly intricate designs, thus making her art a powerful reflection of her life as an Anmatyerr woman and how she experienced her home country.

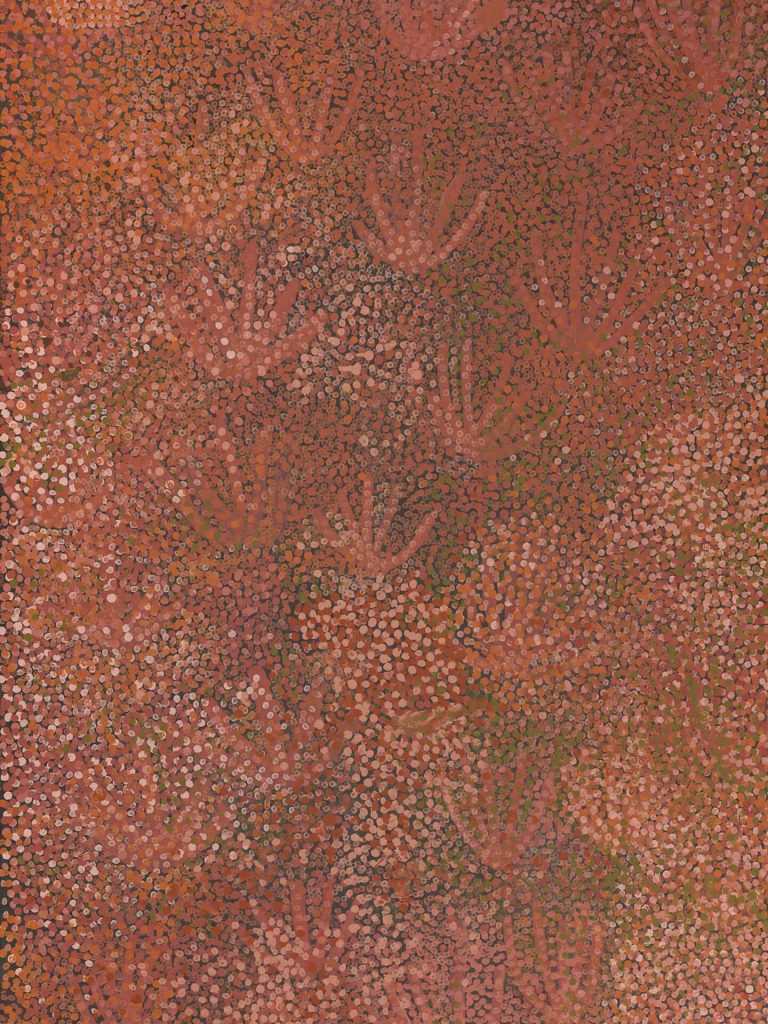

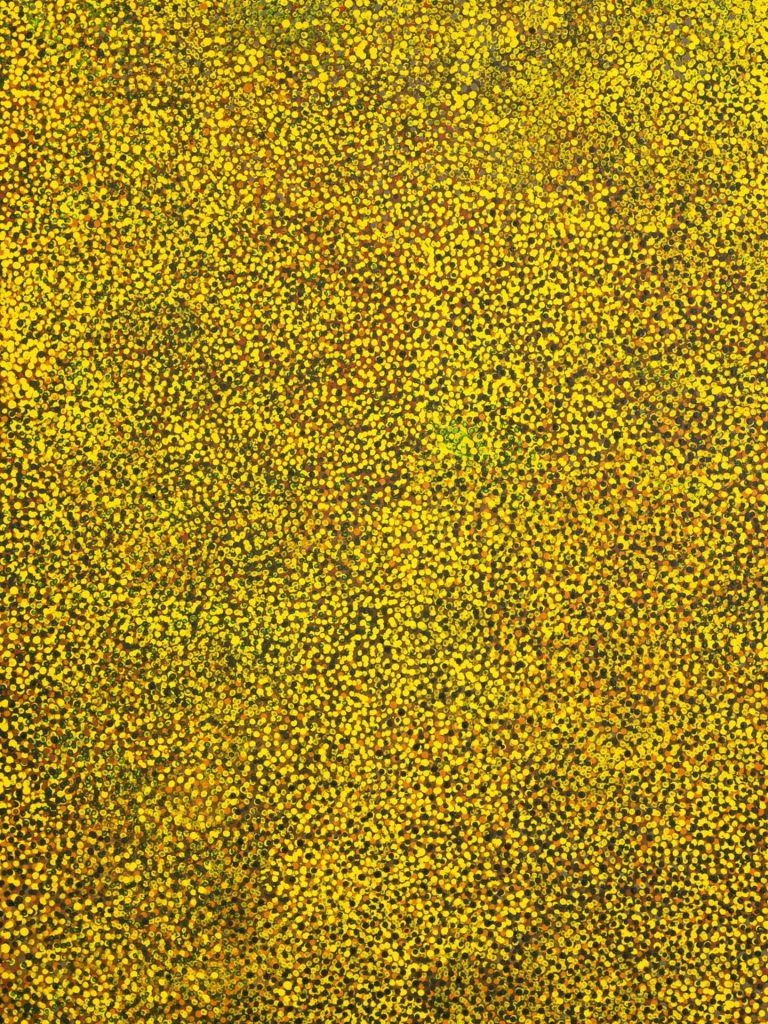

While at first glance some of Kngwarray’s artworks might appear entirely abstract, her work is in fact loaded with private references to the place where she was born and raised, and the traditions upheld within it. For example, her scattered arrays of dots represent the seeds that carry life throughout Alhalkere, while the colours she used were chosen to respond to changing seasons within the landscape. We also see various references animal and plant species that are distinct to the region, including the highly respected emu bird, and her patterns also contained other hidden stories known best to those with whom she shares her ancestral connections.

Wider awareness of the striking work being produced by the batik group grew during the 1980s through a series of exhibitions and initiatives, and Kngwarray, along with many of her fellow makers, became recognised in the Australian and international art scenes. From here, Kngwarray moved on to painting with acrylic paint on canvas, producing often vastly-scaled, monumental works of art with an increasingly complex visual language that continued to reflect on the cultural heritage of her ancestry.

While the dense, web-like structures and patterns in Kngwarray’s artwork have often been considered a counterpart to that of other modernist abstract artists, such as Jackson Pollock and Sol LeWitt, critics today insist we see and appreciate her work predominantly within the framework of the artist’s life and ancestry, because those hidden stories, motifs, emblems and traditions can tell us so much about the importance of family, place, and belonging, as well as keeping centuries old traditions alive for many generations to come.

Leave a comment