Re-writing History: The Paper Textiles of Isabelle de Borchgrave

Self-taught Belgian artist Isabelle de Borchgrave had an uncanny ability to transform humble sheets of paper into the texture and pattern of fabric, from the soft silk of satin to the raw texture of linen. She brought them together into the most ornate costumes and dresses which pay homage to the history of fashion and textiles, with life-size replicas of period garments adorned with all the trimmings, from Coco Chanel’s beaded gowns to Elizabethan court fashion. Working from the mid-20th century until her recent passing in 2024, her art became a powerful commentary on the need to preserve sartorial history, which is so loaded with stories about the evolution of society. She said, “It’s very important to have knowledge about the history of fashion. We need to know the past to better understand the present. Everything exists but is recycled with some evolution and another view.”

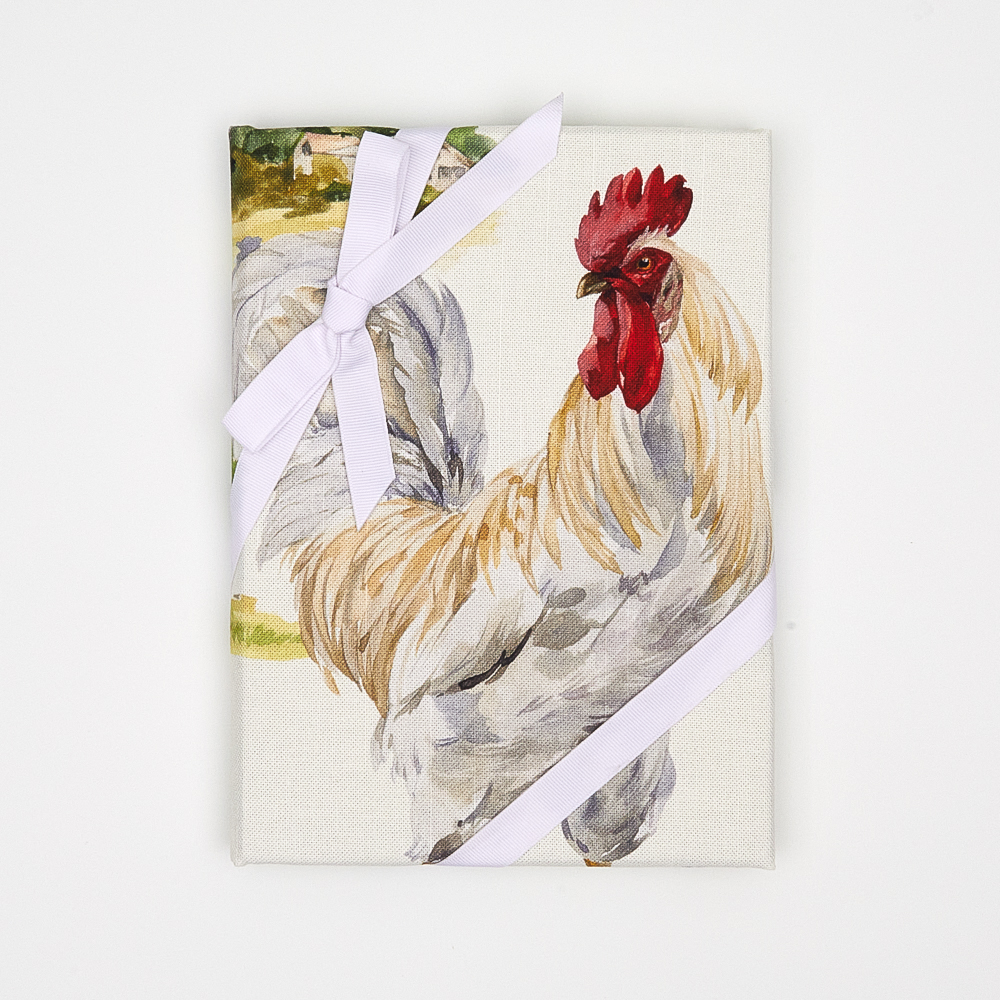

Delphos Dress and Jacket. This two-piece dress, handcrafted from pleated red-hued silk-like paper, is based on a dress created by Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo circa 1924

De Borchgrave was born as Isabelle Jeanne Marie Alice Jacobs in 1946 in Etterbeek, Brussels (she later changed her name following marriage to Count Werner de Borchgrave in 1975). De Borchgrave left school at the age of 14 to study at the Centre des Arts Décoratifs (CAD) before moving on to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. Following graduation, she successfully established a fashion and interior design studio, remembering, “I’ve always loved fabrics, patterns and colours.”

De Borchgrave began working with paper as a means of saving money after realising she could recreate the pattern and surface texture of much more valuable fabrics. She said in an interview, “Because I was poor, too poor to buy fancy linen, etc. … I chose the cheapest medium that existed: paper. I quickly discovered the versatility of paper and the immense possibilities it offered.” The many wearable paper garments she made included a gown for the Queen of Belgium. However, she felt as her commercial work progressed, she was, as she said, “losing her artistic soul.”

In 1994, a visit De Borchgrave made to the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute, where she saw a display of 18th century garments, was just the catalyst she needed to get out of her rut. She said, “I then decided I wanted to tell a story about fashion, so I started creating prints and patterns on paper to create dresses that were unwearable.” De Borchgrave also devoured the museum’s collection of Renaissance portraits, and the elaborate costumes in the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Jean-Antoine Watteau. One of her earliest paper costumes was a recreation of Eleanor de Toledo’s rich brocade gown in Bronzino’s portrait entitled Eleanor of Toledo. However, she later admitted her first shot was a rough around the edges, and it took a great deal of time and perseverance to achieve the right process: “Every day I would learn something new.”

Since then, her paper creations have ranged from the clothing of Marie Antoinette to Ottoman Empire caftans, Queen Elizabeth I’s wardrobe, the gowns of Empress Eugenie of France, Jackie Kennedy’s iconic wardrobe, Frida Kahlo’s Mexican garments, and even pieces from the Ballets Russes archive. Her preferred medium is the pattern paper dressmakers use – “the cheapest you can find,”, for its mutable flexibility. She said, “I was, and still am, surprised every day by what paper can give you. Paper gives you freedom: you can paint on it, shrink it, iron it, and mimic fabrics such as linen, velvet, brocade, taffeta, and satin, by playing with tromp l’oeil and illusion. It’s much more resistant than fabric. It endures better against light and time, with the only issue being humidity.” Each garment could take her months to create, through a process of ironing, cutting, painting, and gluing.

In her later years, she began to understand her life’s work as a response to the times in which she had lived, when discussions around preservation and sustainability are on everyone’s lips. Speaking of the 2020s, she said, “I think this decade with be one of intelligent consumption. We are consciously trying to not use plastic and are going back to the simplicity of paper again. I’m lucky to have chosen paper long ago.”

Leave a comment