From East to West: Isamu Noguchi

The American-Japanese sculptor, furniture designer and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi was one of the most singular and ambitious voices of the 20th century. Throughout his long and prolific career, Noguchi produced gardens, playgrounds, sculptures and monumental public art, along with furniture and architecture, which merged Japanese and American visual culture, and became part of his lifelong goal to bring art out into public, social spaces to improve the lives of ordinary people. He believed, “Sculpture can be a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness.”

Noguchi was born to an American mother and Japanese father in Los Angeles in 1904. When he was two years old, the family moved to Tokyo to live, but Noguchi’s father left when he was still very young. Noguchi grew up in Japan until age 13, living first in Omori, followed by Chigasaki. When he was 13 years old, Noguchi’s mother sent him to the Interlaken School in Rolling Prairie, Indiana, whose educational programme emphasised learning by doing. The shifting nature of Noguchi’s childhood undoubtedly shaped the nature of his identity, and made him feel like an outsider for much of his life, as he explained in an interview, “After all, for one with a background like myself the question of identity is very uncertain. And I think it’s only in art that it was ever possible for me to find any identity at all.”

But, as he later reflected, finding comfort with being alone was fundamental to his development as an artist, as he noted, “One can be an artist and alone, for example. An artist’s life is really a lonely life. It is only when he is lonely that he can really produce. If he is not lonely, he may be a social, nice, person, but you know, he might not be driven to it. After all, in a sense you’re driven to art out of desperation. People are naturally lazy; they don’t do things unless they are driven to it.”

Although Noguchi had the desire to become an artist, he initially set out to train as a doctor at Columbia University in 1922. It was his mother who persuaded him to change track, and study sculpture at the Leonardo da Vinci School of Art in New York. Following graduation, Noguchi found work as an assistant to Constantin Brancusi in Paris. It was here that he first began exploring an interplay between organic shapes and geometry in his sculpture, merging the restrained minimalism and order of Japanese culture with Western elements of expressionism and surrealism. On his return to New York, Noguchi became involved in a series of public art projects, producing designs for memorials and outdoor spaces with a Zen-like quality, as well as set designs for theatre and dance.

Following the Pearl Harbour attack in the United States, Noguchi founded the Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy in 1942, and even admitted himself into an Arizona internment camp for several months, hoping to help improve the lives of detainees, although budget cuts meant he was unable to carry out the plans he had hoped for.

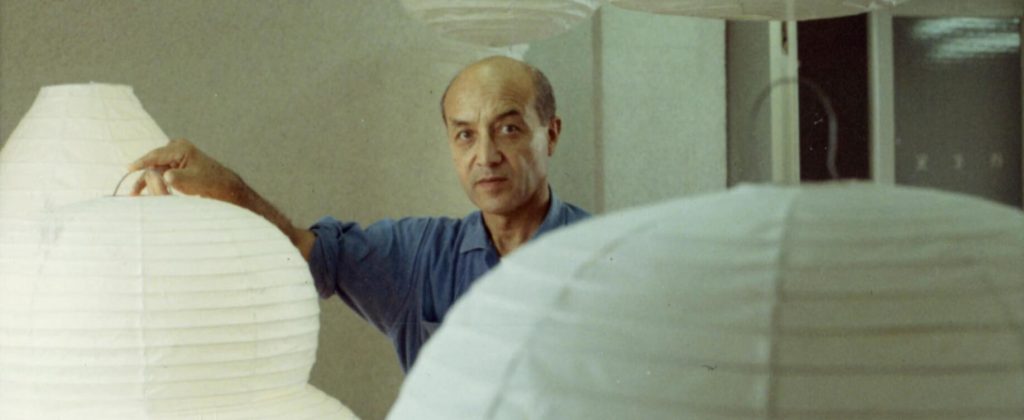

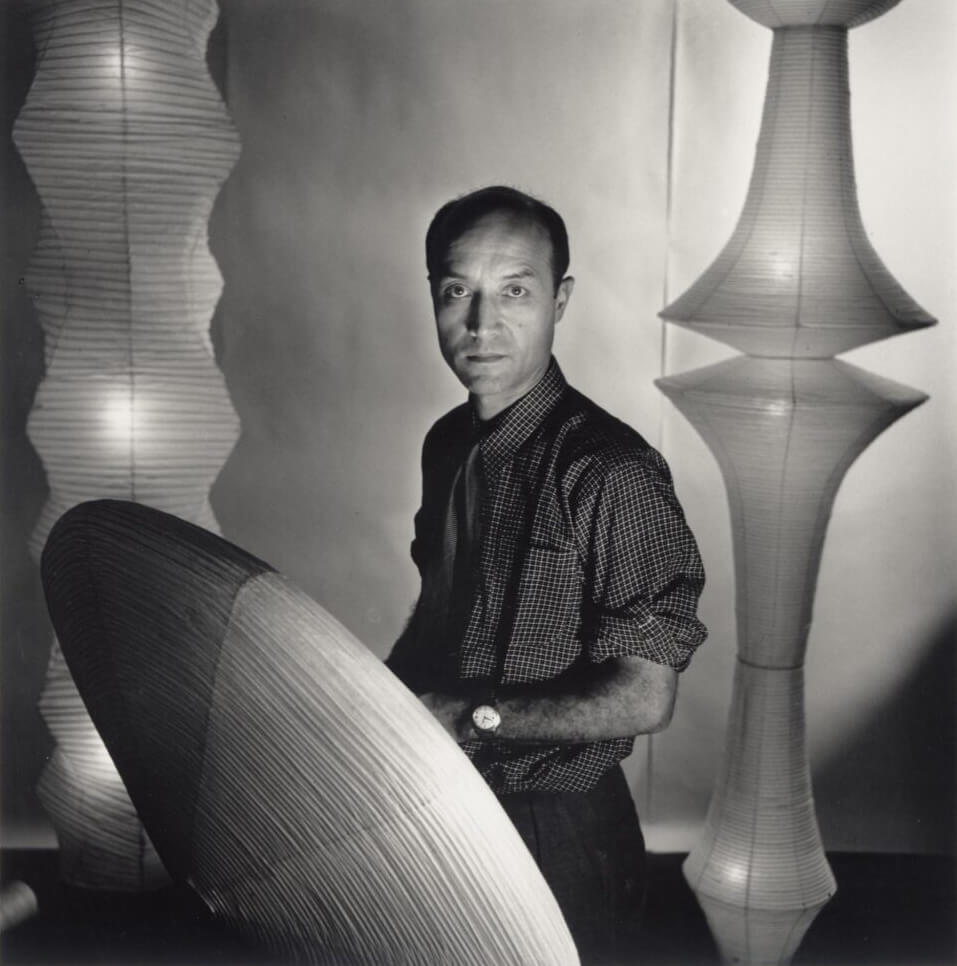

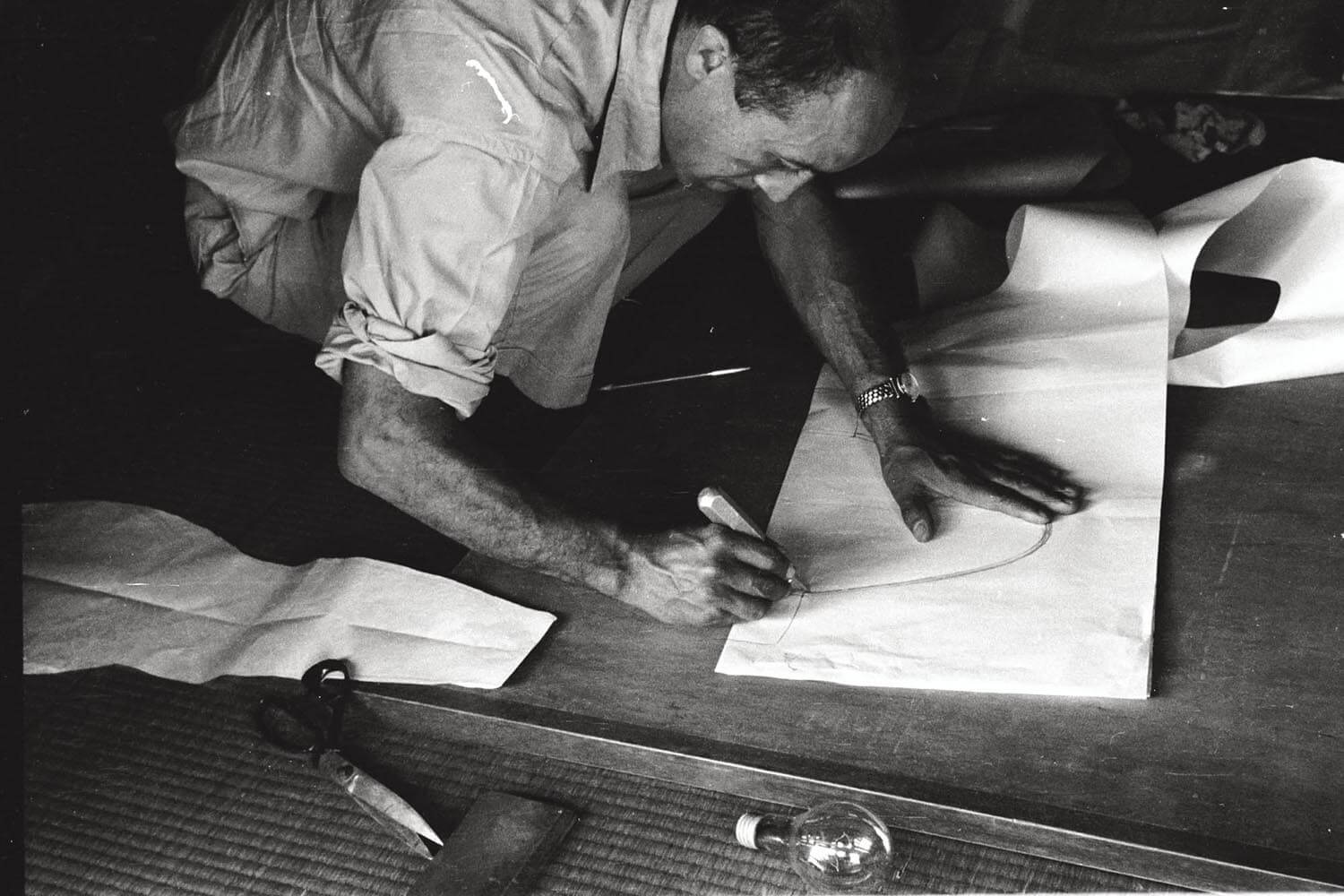

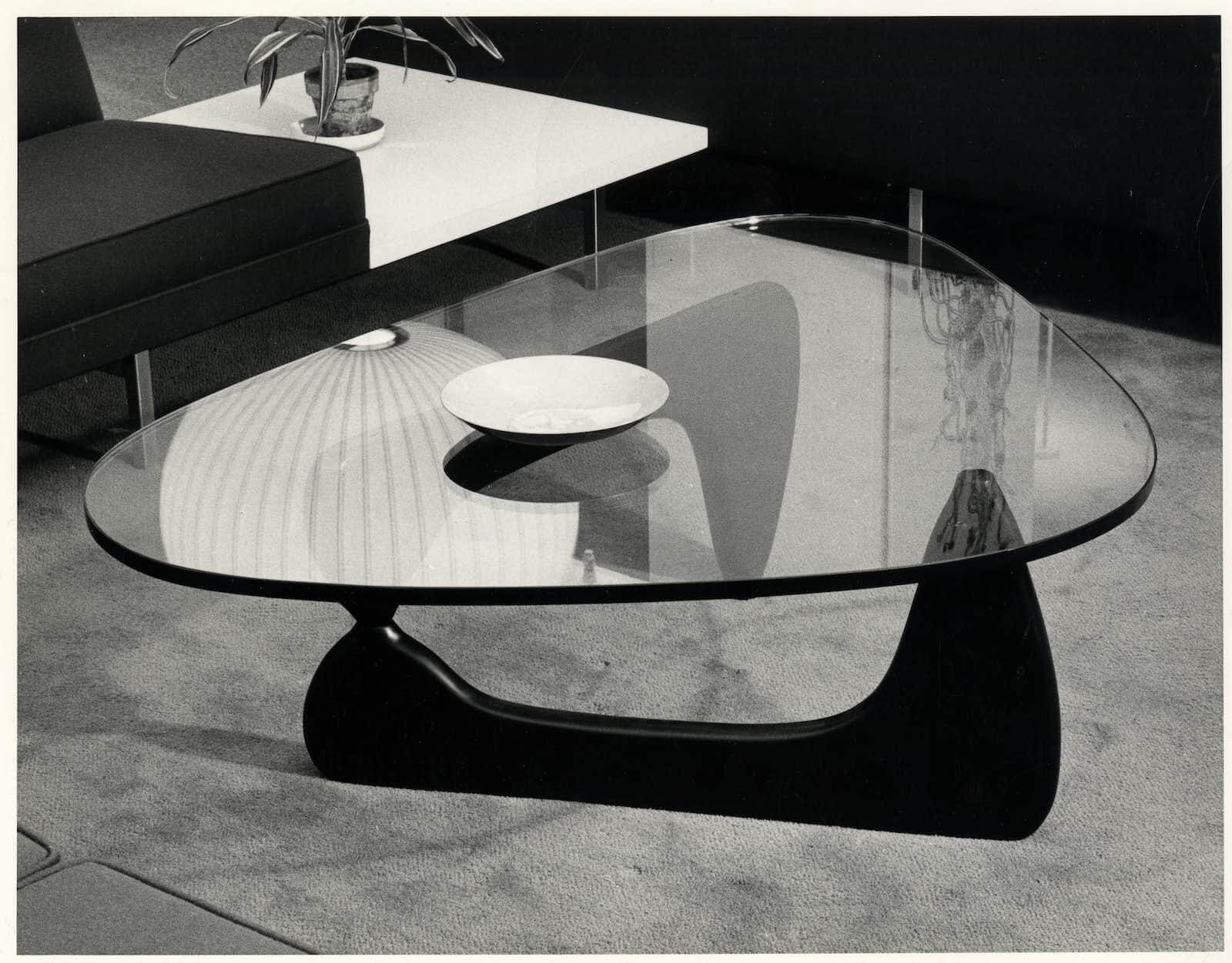

It was during the 1940s the Noguchi first began creating his free-standing, Surrealist sculptures. He began a working partnership with furniture maker Herman Miller for whom he designed his famed Noguchi coffee table, considered one of the symbols of modernism. He also created sculptures with light as a key component, along with Akari lamps for furnishing company Knoll that fused elements of product design and art into one. These designs merged the elegant restraint of Japanese design with the curvaceous forms of modernism.

After the war Noguchi was able to secure funding for a greater range of public art projects, with a focus predominantly on a series of monumental, sculptural gardens. For the remainder of his career, Noguchi spent time integrating his love of nature into forms of public art that could be enjoyed en masse. The result was a series of deeply contemplative spaces with a balance between contemplative order and improvised expressionism, ideas that reached their zenith in the Noguchi Museum and Garden in Long Island City, completed in 1987. Noguchi explained in an interview in his later years how gardens had become the ideal playground for creative expression, observing, “I like to think of gardens as sculpturing of space: a beginning, and a groping to another level of sculptural experience and use: a total sculpture space experience beyond individual sculptures.”

3 Comments

Eshaal Fatima

Isamu Noguchi’s work beautifully combined Japanese and American culture, creating art that was both functional and socially impactful. His vision of bringing art into public spaces is truly inspiring. Speaking of functionality, for reliable Chiller Van Services, http://www.chillervanservices.com for all your cooling needs!

Ann Scott

I first saw Noguchi’s work when I was very young and my mother took me to see Martha Graham dance in New York. Noguchi designed the sets for several of the dances. That experience changed my life. Seeing what two distinct artists could accomplish when in harmony. Thank you for taking me back there for a moment.

Emily Ulrich

Oh Rosie! I have always loved Noguchi’s work. He was a master of everything! Thank you for highlighting him.