Spirit and Life: Henry Moore’s Vibrant Textiles

20th century British artist Henry Moore’s monumental sculpture is widely known and celebrated across the world, but perhaps less well studied is his intriguing relationship with textiles. During the 1940s and 1950s, Moore produced a body of textile designs, which open up a new understanding of his visual language, and his way of seeing and understanding the world. His textiles feature vivid, unconventional colourways and lively, spirited patterns that depart in surprising ways from the more muted colour schemes of his sculpture and work on paper. Moore’s textiles were a commercial success during the mid-20th century, and later made their way into high-profile fashion lines by renowned design houses Paul Smith and Burberry.

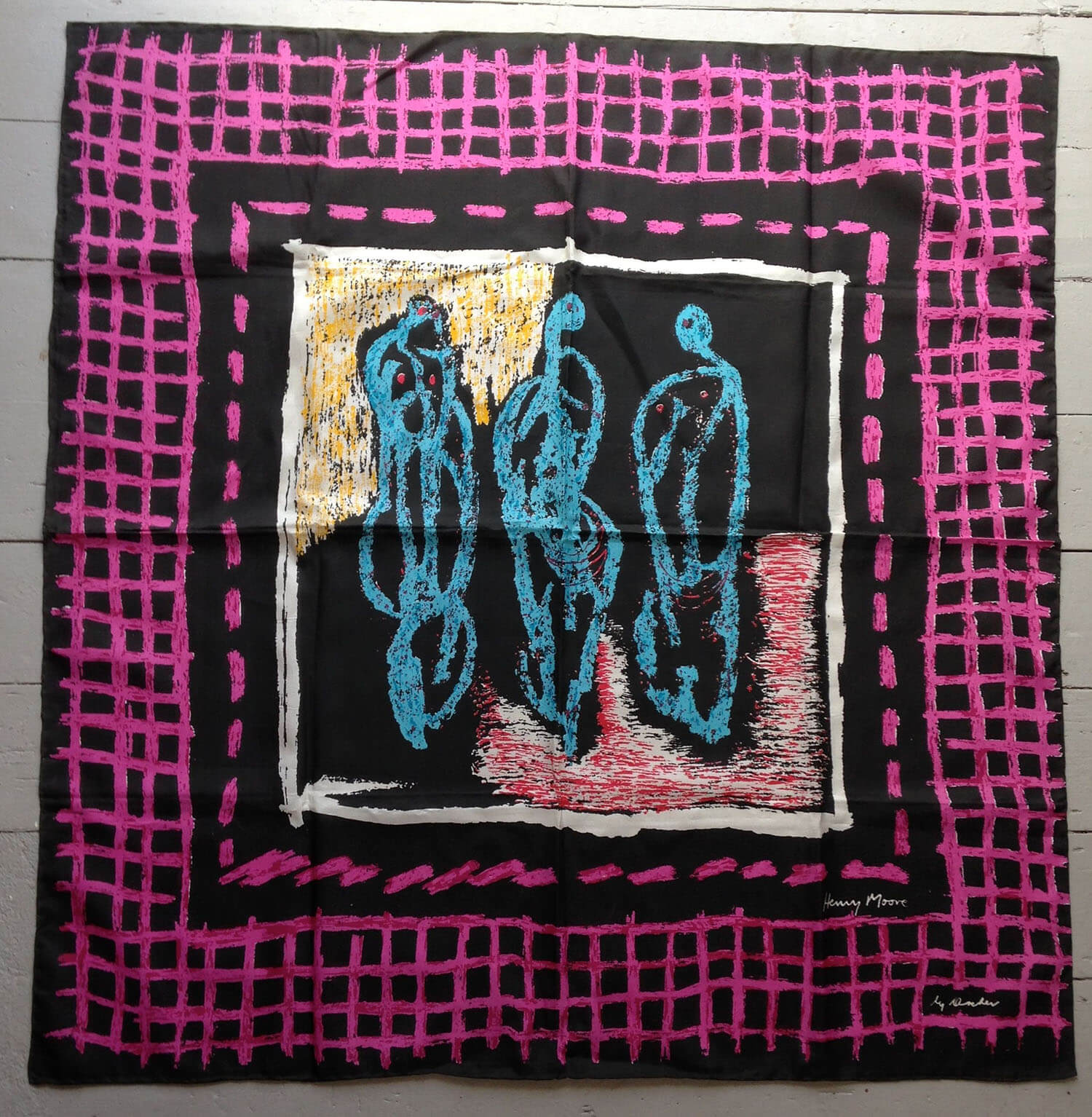

Henry Moore was first introduced to the realm of textile design through artist and designer Zika Ascher, who owned a textile business in London. During the 1940s, Ascher invited a group of 45 internationally renowned artists to produce a limited-edition series of textile prints for silk headscarves, known as Ascher squares. These fabrics were part of Ascher’s goal to democratise art by making it accessible to the wider public. Ascher also hoped they would lift spirits and boost public morale in the wake of World War II, as well as opening up an international network between artists whose lives had been separated by the war. Moore was one of 45 artists invited to take part, alongside various others including Henri Matisse, Sonia Delaunay, Pablo Picasso and Paul Nash.

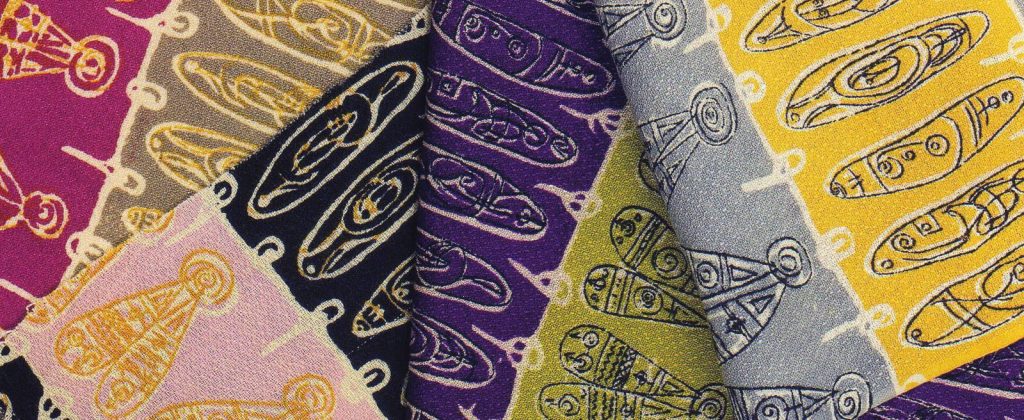

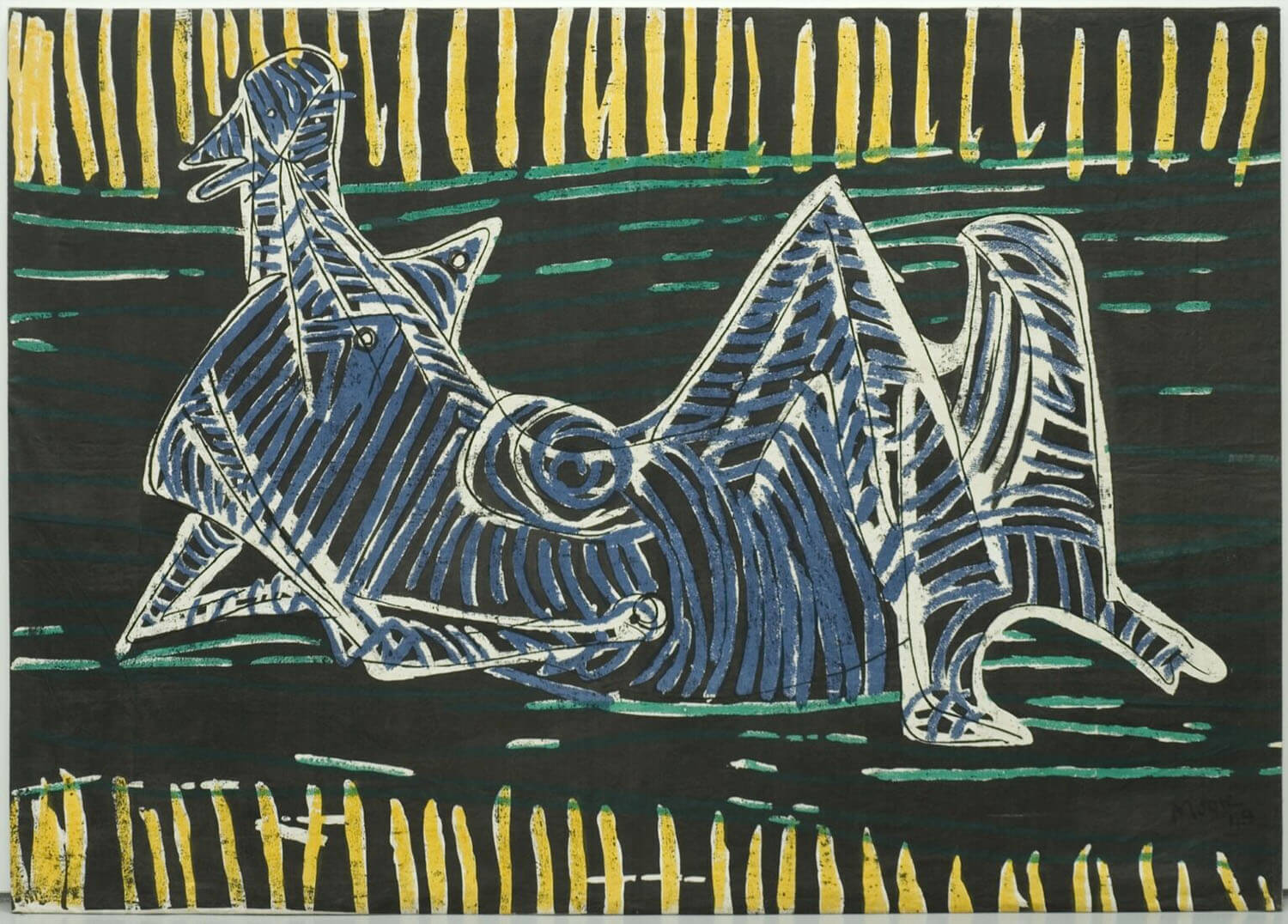

While working for Ascher, Moore quickly became fascinated by the possibilities of commercial textiles, and his sketchbooks from 1944 to 1946 are filled with a bountiful array of hand-drawn ideas for textile patterns. Moore incorporated playful emblems like piano keys, caterpillars, boomerangs and trains, with edgy, unconventional additions including barbed wire and safety pins that hint at the underlying threat still looming large in postwar Britain. Meanwhile emblems such as clock hands point to the artist’s pre-war forays into Surrealism.

Henry Moore, Reclining Figures fabric, 1944-46, serigraphy in 6 colours, cotton, Gray M.C.A. Source: Cover Magazine

He realised these motifs with striking, contrasting colours including bright green, orange, lemon yellow, and hot pink, intense shades that had not been seen in his artistic practice before, and which injected a burst of vibrancy into the subdued atmosphere of British life. While only a handful of these designs made their way into hand-printed production, they were a commercial success, prompting Moore to return to designing textiles in the following years. Henry Moore and his wife Irina Moore also saw the production of fabrics as a a means of making art more accessible and they even integrated his fabrics into their family home in Hoglands.

In the 1950s, Moore produced a new series of textile designs in the early 1950s for David Whitehead Fabrics following the Festival of Britain. The work that emerged from this prolific period in the artist’s life were translated into silk squares, upholstery and dress fabrics, and wall hangings. In contrast with his hand-printed designs for Ascher, David Whitehead Fabrics used a semi-automatic process to recreate the artist’s designs, feeding the fabric under a series of flat printing screens that still retained the same hand-made, painterly quality as Moore’s earlier fabrics.

While Moore’s fabrics have been overshadowed by the success of his sculptural work, in recent years, Anita Feldman, a leading authority on the work of Henry Moore, is one of numerous experts playing a pivotal role in bringing this fascinating and under-appreciated aspect of the artist’s work into the public eye. Her series of exhibitions and accompanying publication showcase not just the artist’s designs that were commercially produced, but also the behind-the-scenes sketchbooks, studies, and unrealised ideas that have previously remained unseen and unknown, opening up new pathways into Moore’s enduring artistic practice.

One Comment

Vicki Lang

What a wonderful talent. His fabric is beautiful and so unique.