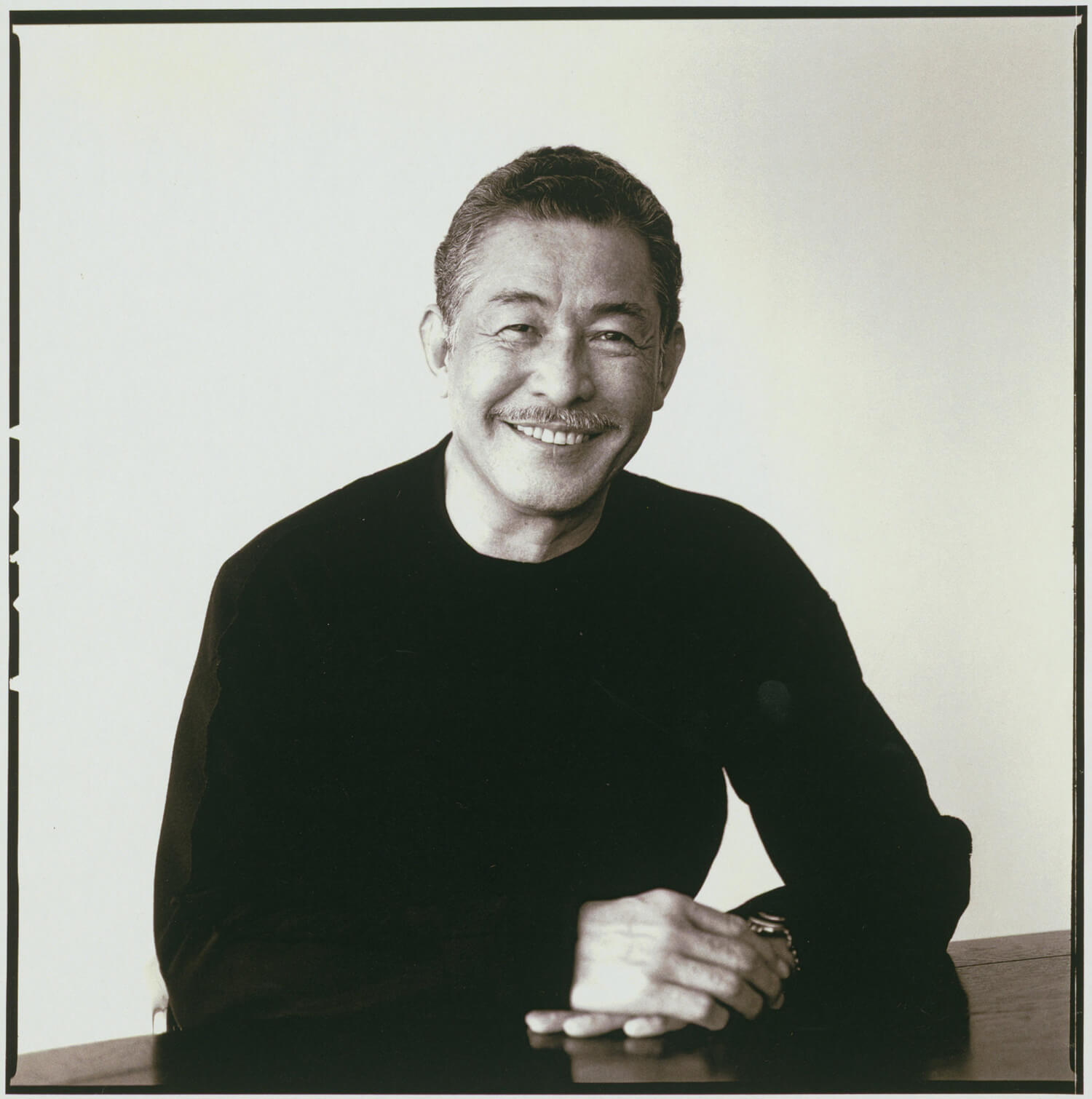

Designs for Life: Issey Miyake

Japanese fashion designer and powerhouse Issey Miyake cared deeply about the relationship between clothing and the living, breathing bodies that inhabited them. He designed clothes that were meant to be worn, believing they were only truly complete once they had been integrated into the lives of their wearers. Yet there was nothing ordinary or basic about his garments which fused Japanese traditions with cutting-edge technology, forming a remarkable blend between creativity and pragmatism. He said, “I am neither a writer nor a theorist. For a person who creates things, to utter too many words is to regulate himself, a frightening prospect.”

Miyake was born in Hiroshima in 1938. He was just seven years old when the catastrophic atomic bomb hit. Three years later, his mother tragically died after suffering from radiation poisoning. Miyake also suffered some ill-health, and the experience left him wondering if he would ever reach adulthood. Such a close brush with death gave Miyake the drive to seize every moment he could, and chase his creative dreams. He took painting classes as a young child, and years later developed an interest in fashion after reading his sister’s magazines. But in 1950s Japan- men were not allowed to study fashion; instead Miyake trained as a graphic designer at Tama Art University in Tokyo.

Following graduation Miyake travelled to Paris, training in couture at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. After spending several years training in exclusive Parisian fashion houses, Miyake turned his attention towards a more democratic approach, or what he called, “an easy style, like that of jeans and a T-shirt, but one that could be worn in a wider milieu, regardless of age or profession.”

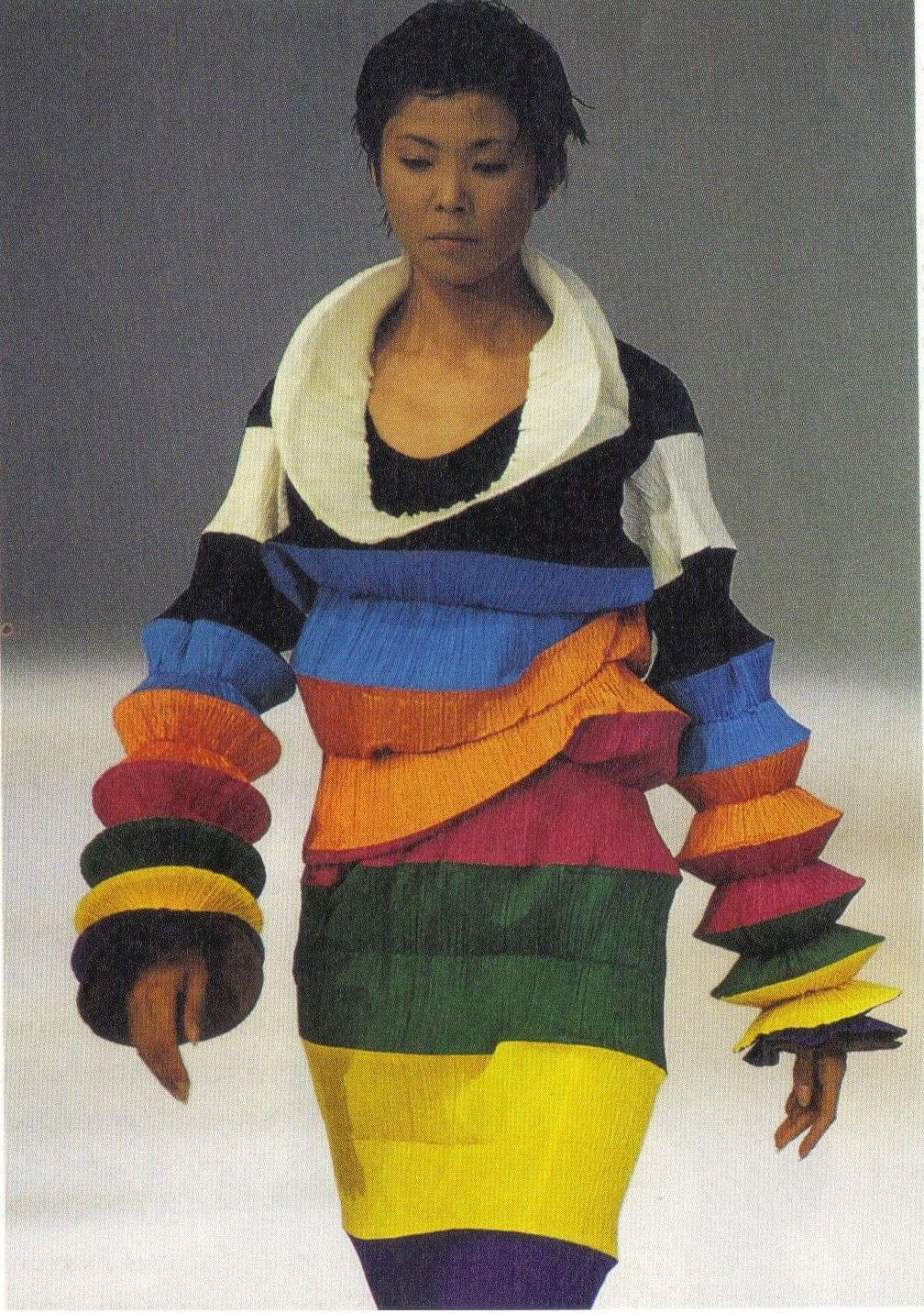

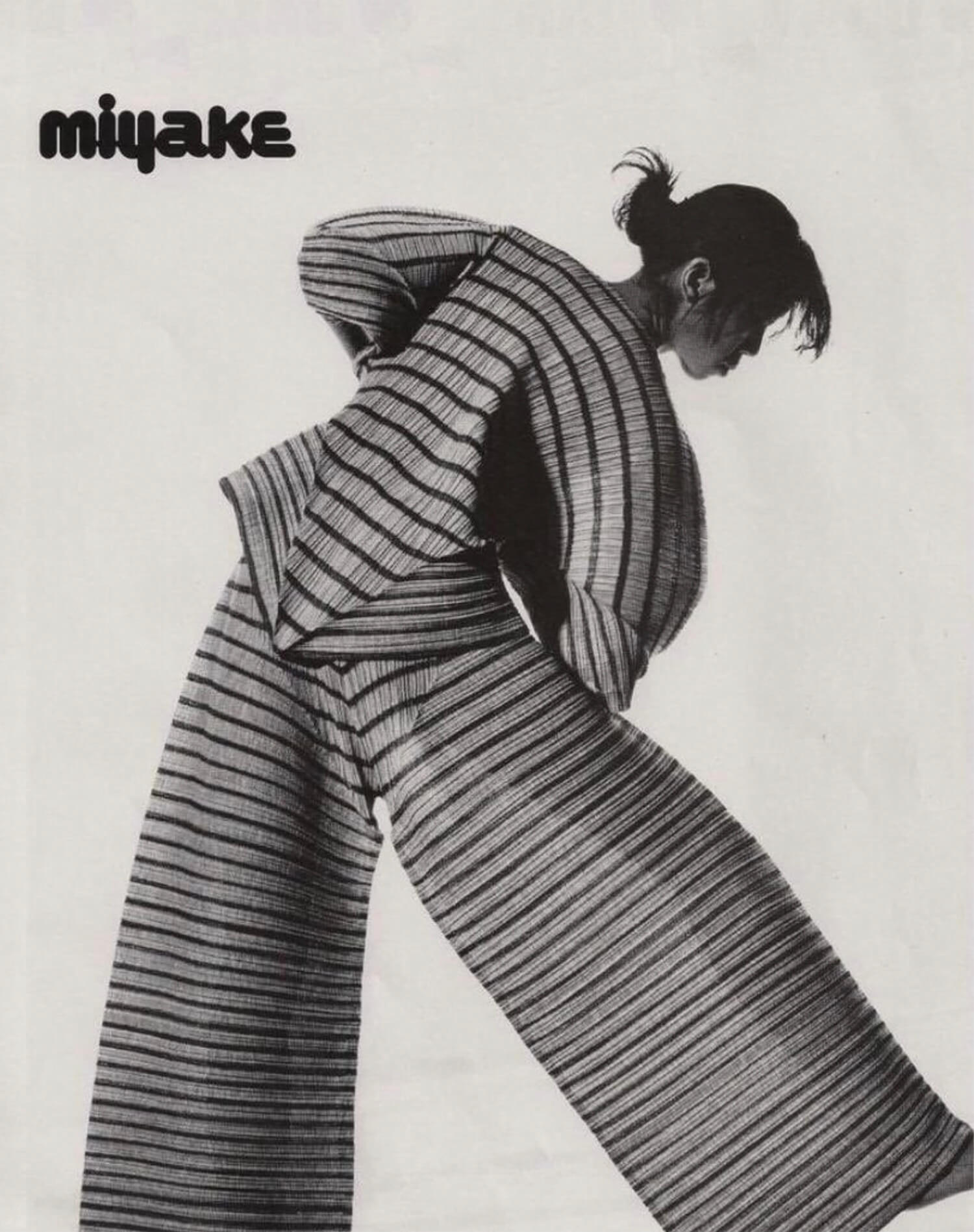

In 1969 Miyake travelled to New York, where he became an assistant for Geoffrey Beene, learning about producing for a mass market. In 1970, he established Miyake Design Studio in Tokyo, from where he began producing striking, sculptural garments which demonstrated a complex, enquiring mind at work. In some clothing he adopted the Japanese tradition of folding rectangular fabric pieces and stitching them into clothing. Miyake also pioneered the innovative use of unconventional materials, ranging from heat-baked polyester to wood cellulose, recycled plastic, and digitally-designed tubular fabrics, arguing, “Material for clothing is limitless: anything can make clothing.”

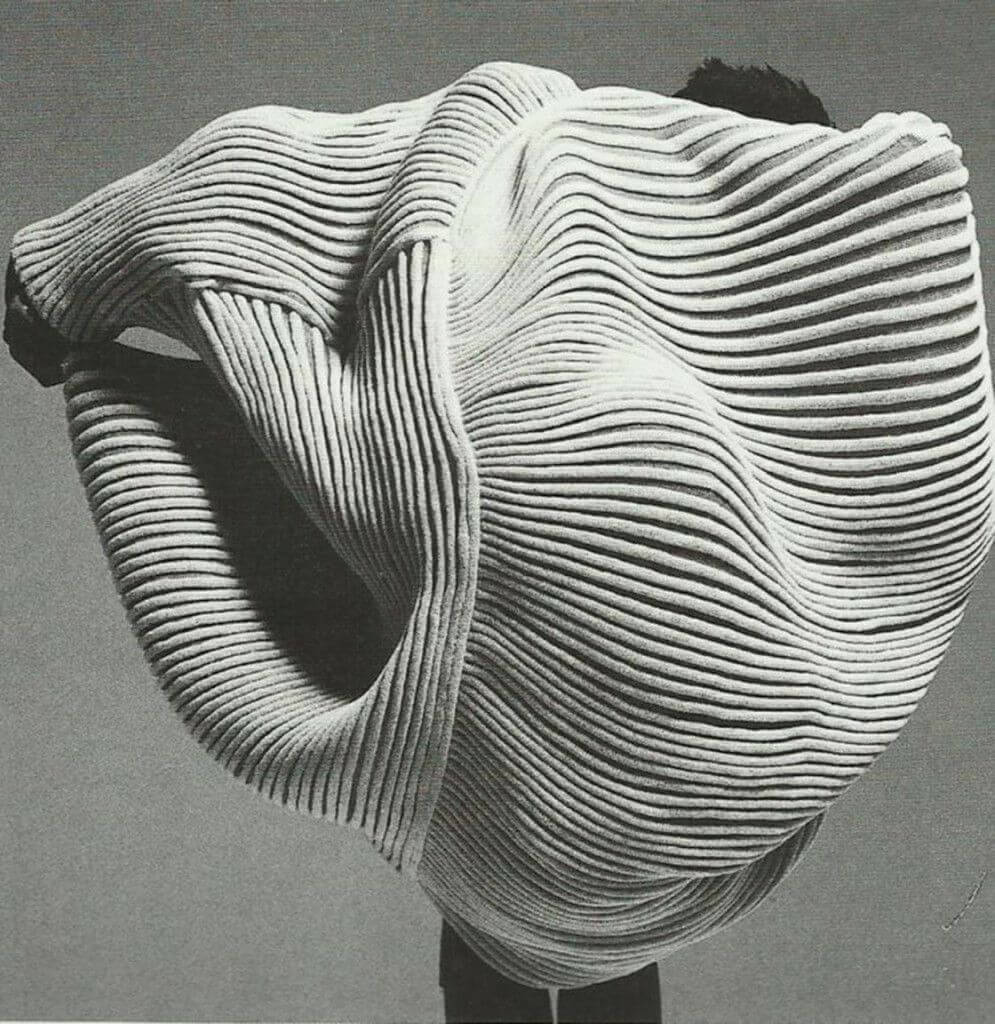

The designer launched his famed Pleats Please concept during the late 1980s, in which he integrated his signature garment-folding process. The fabric for this line was constructed from a single thread, sewn into shape, and formed into folding the designer’s trademark pleats, which resulted in lightweight, crease-free clothing with a subtle, ripple-like effect. Such was the success of the range, which emphasised movement, comfort, and wearability, Miyake expanded the process into its own standalone fashion brand, which is alive and well today. A large part of the brand’s success has been the durability of the clothing, which Miyake has adapted for both clothing and stage costume. “When I make something, it’s only half finished,” he said, “When people use it – for years and years – then it is finished.”

Over time, Miyake expanded his design brand across 8 different lines, including fashion, product design, and perfume, finding his milieu in the mass market. In his later years, he turned each one over to new management, and focussed his attention on his Tokyo Reality Lab, a multi-level boutique slash gallery, and development space where young designers could receive training from Miyake’s longest standing members of staff. The facility was designed to showcase Miyake’s enduring love of design, and the key role it can play in enhancing our daily lives. He famously said, “Design is not for philosophy – it’s for life.”

One Comment

Kate Renwick

I love Miyaki’s work. I couldn’t wear it but love seeing it.. he’s designing on so many levels.

I love your articles too Rosie.