The Architect of Couture: Madeleine Vionnet

The renowned Parisian, inter-war fashion designer Madeleine Vionnet earned the moniker of “architect of couture” amongst her peers during her lifetime, for her innately structural approach to clothing. Her garments were constructed using the diagonal bias cut as a prominent feature, along with Grecian-style drapery, to create the most striking, theatrical visual impact. Much like Madame Gres, Vionnet worked like a sculptor, designing her clothing in the round to gain an understanding of their form from every single angle. This daring and experimental approach to fashion played a pivotal role in revolutionizing women’s clothing for the 20th century.

Madeleine Vionnet was born in 1876 in Chilleurs-aux-Bois Loiret. Her first experience in fashion came at the tender age of 12, when she took on an apprenticeship as a seamstress and lace maker, setting the foundations for her future career. After dealing with a broken marriage and the loss of a child when she was 18, Vionnet left France for London in search of a new beginning. Her first role in London as a hospital seamstress paved the way for work as a fashion fitter for couturier Kate Reily in around 1897.

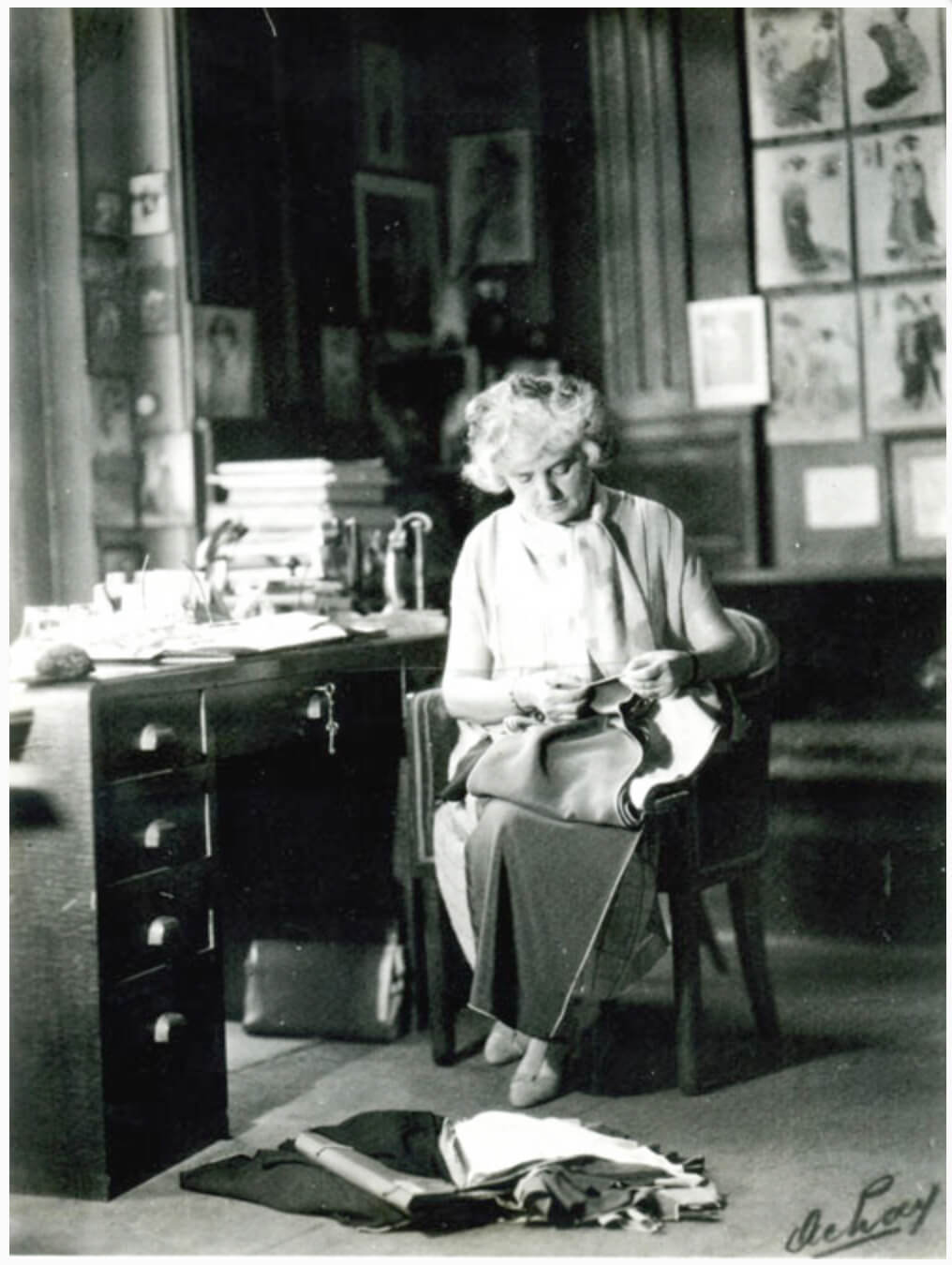

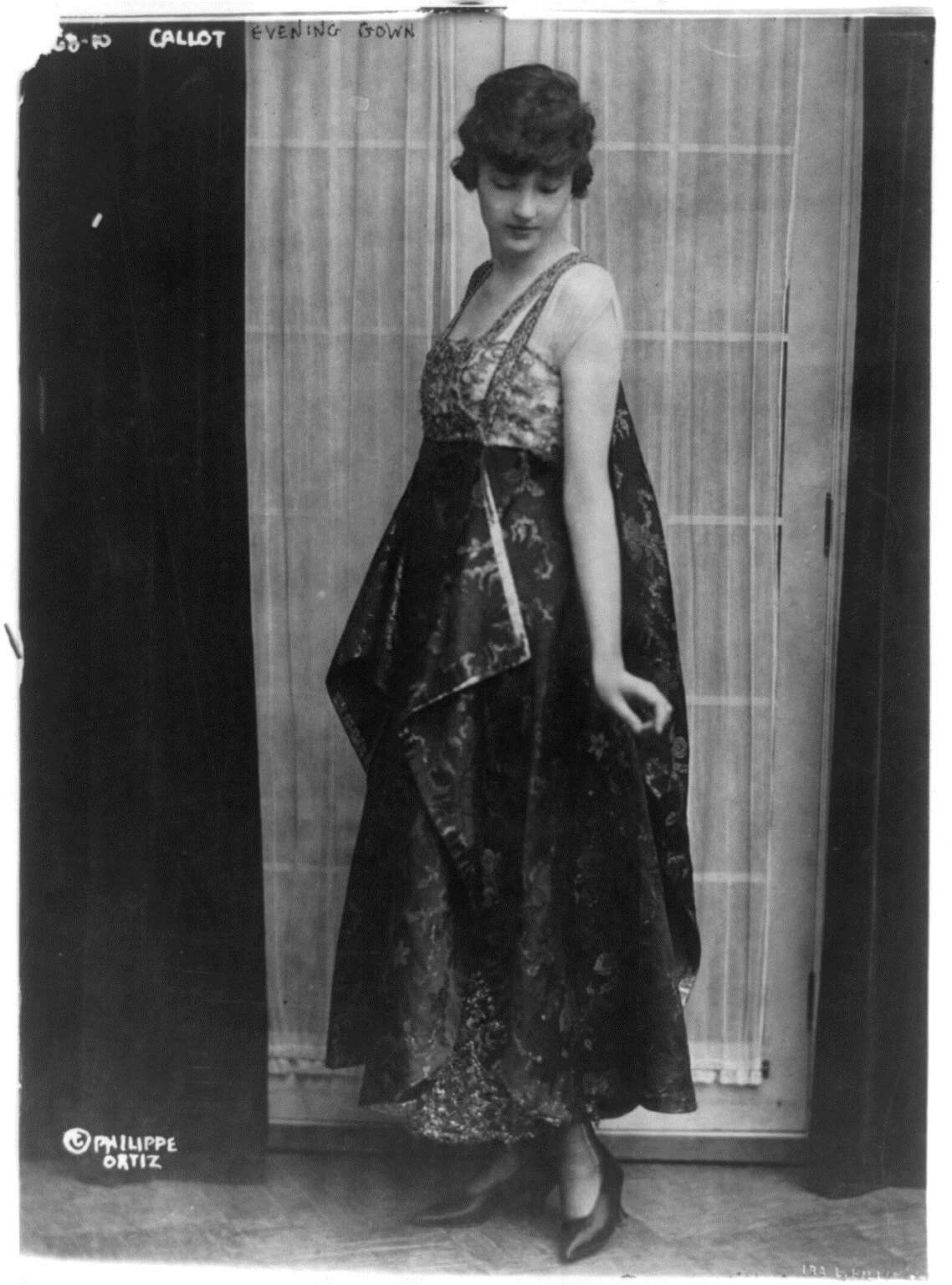

Following a return to Paris in 1900, Vionnet worked for the renowned fashion house Callot Soeurs as a toile maker, where she worked closely alongside Marie Callot Gerber, and it was here that Vionnet first began producing draped designs directly on models and smaller, three-dimensional mannequins. Spotting her creative talent, French couturier Jacques Doucet persuaded Vionnet to join him as an ambassador for his younger clientele, who were looking for clothing that freed them from constrictive corsetry.

Under Doucet’s wing, Vionnet found herself increasingly drawn towards the sinuous, flowing qualities of fabric in Greek art, and the ways in which it seemed to organically contour itself to curvature of the female body, a far cry from the uncomfortable, structured couture of her youth. She was equally influenced by the bodily movements of Isadora Duncan, whose modern dance ushered in a new brand of femininity.

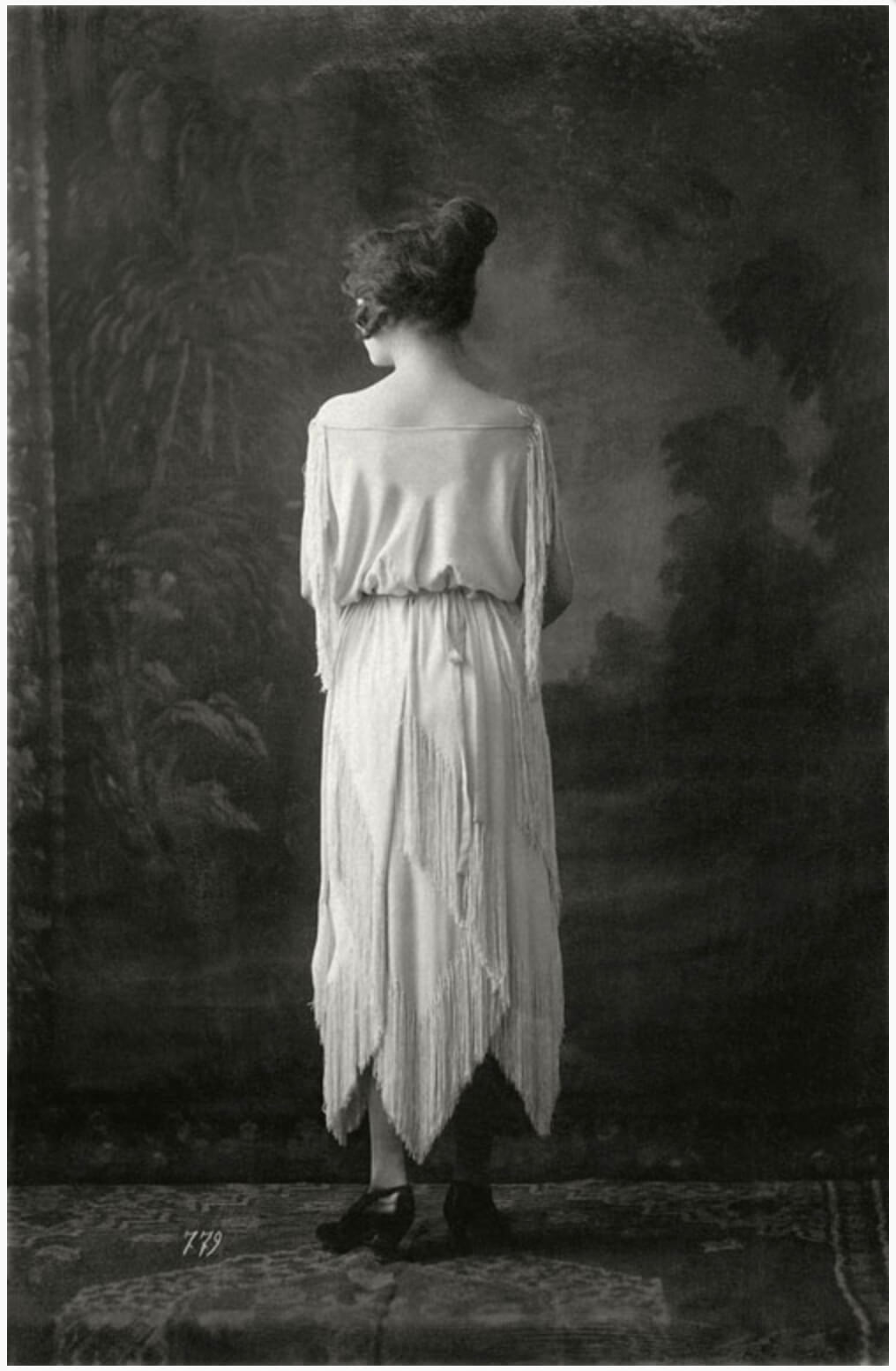

Branching out on her own, Vionnet opened her own house called, simply, ‘Vionnet’, on the Rue de Rivoli, in 1912. Her breakthrough moment came in the 1920s, when Vionnet began working predominantly with bias cut clothing, deliberately cutting diagonally against the grain of the fabric. This approach allowed her dresses and gowns to cling closely to her models’ frames, and to create elegant drapery that moved with the body. Vionnet worked with lightweight, airy silk fabrics including crepe and chiffon, for their ability to hang seamlessly from her wearers’ frames. Some of her key, signature pieces – still in circulation today – include the halter neck top, the cowl neck, and the handkerchief dress, deceptively simple designs which playfully accentuate the wearer’s form.

Vionnet gathered a widespread following during her lifetime, first in Paris, and later internationally, with her gowns appearing on the leading silver screen actresses of the day, including Katharine Hepburn, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Joan Crawford. The sleek, flowing style she pioneered, which celebrated freedom and movement, became synonymous with the 1930s, a time when women were increasingly emancipated from the constraints of Victorian society. They also chimed with the Art Deco obsession with motion. Yet Vionnet shied away from following trends or chasing publicity, choosing instead to lean towards what she saw as a classic, understated elegance.

A designer’s designer from the outset, Vionnet’s approach to clothing has had a remarkable impact on artists and fashion designers through the decades, including Issey Miyake, Azzadine Alaia, and John Galliano. Many leading photographers of her day documented Vionnet’s work, including Edward Steichen, Cecil Beaton, Man Ray, and Horst P Horst, who were able to capture the exquisite artistry that went into every garment Vionnet made. In 1925, British Vogue brilliantly summed up this radical designer’s legacy, calling Vionnet, “perhaps the greatest geometrician among all French couturiers”.

4 Comments

Maureen Christensen

What a beautiful article… I love to learn about women who go for it and follow their passion and dreams. The pictures were fabulous too. This tempts me to try to make something on the bias!

E S Desanna

Nice to see an article on my favorite coutouriere. Just a tweak to the fabrication you mention: the chiffon and crepe are types of silk, not a different textile. Velvet, satin, broadcloth, shantung, georgette can all be woven of silk. Then there’s silk jersey, yarn for sweaters…

This not meant to embarass you. The article was excellent. After 65 years immersed in fashion, fabric & sewing, having owned fabric stores, custom design businesses, and teaching college level fashion design, I feel obligated to educate where I can.

Lily Amelia

Hi E S Desanna,

I hope you are well.

My name is Lily Amelia, I am an aspiring fashion designer. I saw your comment and I was wondering if you had any advice about fabrics or learning about fabrics.

Kind Regards,

Lily Amelia

Robin Geisler

Reading your “history” lesson is the best part of my day. I am so inspired by these creative and brave barrier breaking people.