Drapes and Columns: The Statuesque Fashion of Madame Grès

French dressmaker Madame Alix Grès made her name in the mid-20th century with sleek, minimal garments that mimed the slender, vertical lines of Greco-Roman architecture. An outlier in the fashion world, she eschewed mid-20th century trends for a timeless elegance, forging her own singular path. Madame Grès’s aspirations to become a sculptor were quashed by her parents and as her career in fashion progressed, she continued to approach fashion with the eye of an artist, emphasising the aesthetic qualities of form, volume and drape. She said, “I wanted to be a sculptor. For me, it’s the same thing to work the fabric or the stone.”

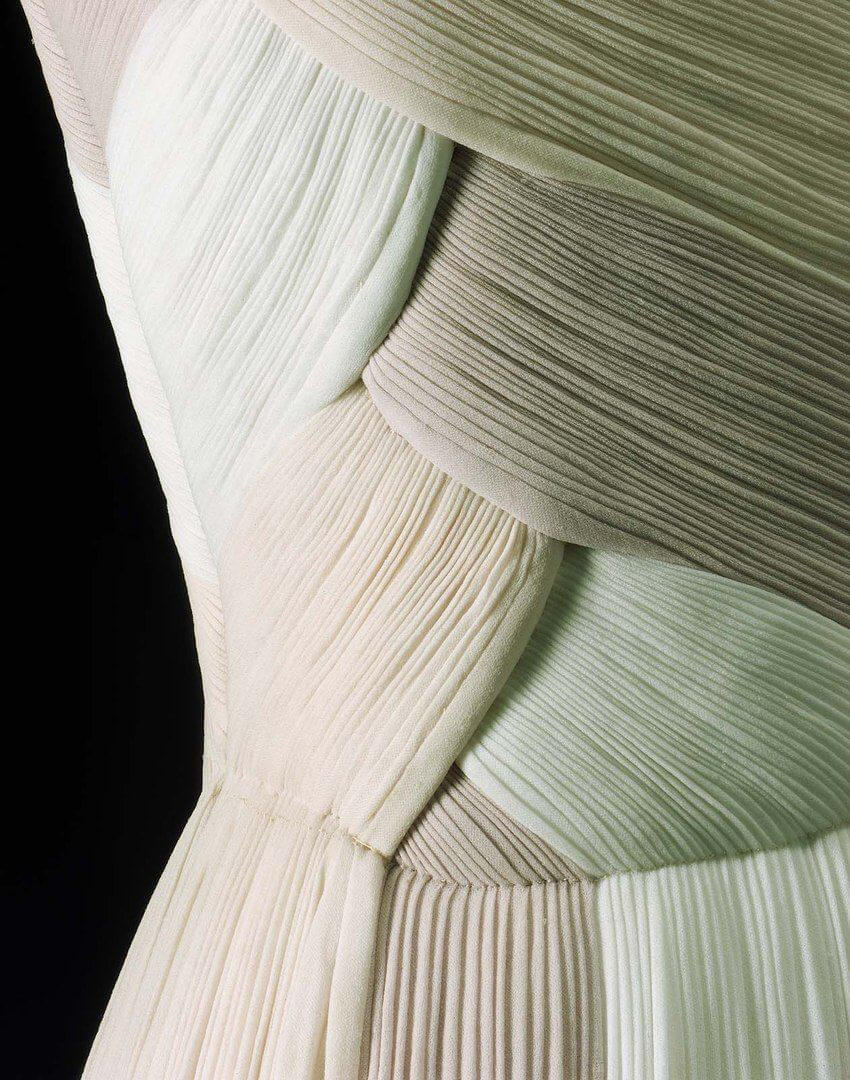

Born as Germaine Krebs in 1903, the designer took up her first apprenticeship in fashion with Premet in Paris. Her working designer name was Alix Barton, and her first fashion line was produced under the name Alix. Following a stint working as a theatre costumier, she went on to develop her trademark, almost instantly recognisable style – using intricately complex systems of pleating, drapery and tucking with softly flowing fabric to create garments with a statuesque, Grecian quality.

Following her marriage to Russian painter Serge Czerefkov in 1940, she invented the professional name Grès, as an amalgamation of her husband’s first name (her various names have prompted some to call her the ‘sphinx of fashion’). After establishing her own fashion maison on the rue de Paix in 1942, Grès worked tirelessly building up her brand, remaining steadfastly true to the principles of her earlier work. She said, “For a dress to survive from one era to the next, it must be marked with an extreme purity.” Such was her success, during her lifetime, she made clothing for Grace Kelly, Greta Garbo, and Marlene Deitrich, while The New York Times called her house, “The most intellectual place in Europe to buy clothes.”

Each dress in Grès’ collection took around 300 hours to create, with every pleat produced by hand, making every garment an individual work of art. Grès could incorporate up to 65 yards of thin, silk jersey or taffeta fabric into her dresses, but they were sometimes anchored by a bone bodice, adding structure to her designs.

As a general rule Grès veered away from excess sewing, choosing instead to devote her time to the drape and fall of fabric directly on her models, moving around them for hours to position the fabric in the most elegant and flattering way, rather than working up directly from toiles and patterns. Grès was also a pioneer in introducing cutouts to women’s formalwear. “Cutting is the most important stage in creating a dress,” she once said. “For every collection that I produce, I wear out three pairs of scissors.”

Grès remained in the same fashion house until her retirement in the 1980s. Her reluctance to adopt the ‘ready-to-wear’ accessibility of her younger peers led to her ultimate demise – the company was forced into liquidation in 1987. Her insistent refusal to bow to market trends has made Grès’ legacy as a sculptor of fabric remain steadfast and true, which has been proven in the numerous retrospectives of her fashion-as-art staged following her death in 1993.

Today, Grès’ designs are still a popular choice on the red carpet, and they appear as timeless and elegant as they always have, with none of the stylised, vintage quality one might see in the work of her peers. Meanwhile, Grès’ influence on the fashion landscape has been profound, shaping the designs of Rick Owens, Halston, Sophia Kokosalaki, Issey Miyake, Yves Saint Laurent, and perhaps most profoundly, Alaïa. Reflecting on the nature of her designs, while simultaneously summing up her entire career, Grès wrote, “Perfection is one of the goals I’m seeking.”

2 Comments

Terry Green

Wow!!! Such beauty, precission and artistry?

Kelly Singh

What an amazing artist! The fluidity and drape of those designs is one of a kind. Thank you for sharing.