Chance and Freedom: The Whimsical Textiles of Josef Frank

Artist, designer and thinker, Josef Frank was an outspoken pioneer, whose practice spanned diverse disciplines, including art, architecture and textiles. In his textile and embroidery work he broke away from the simplicity of modernism with fluid, organic repeat patterns designed entirely by hand, featuring swirling flora and fauna in bold, Matisse-like motifs and intensely vivid colour pathways that became monumentally successful. Frank wrote, “Away with universal styles. Away with the idea of equating art and industry, away with the whole system that has become popular under the name of functionalism.”

Josef Frank was born in 1885 to a middle-class Jewish family in Vienna. He trained as an architect at Konstgewerbeschule, followed by a productive spell designing houses and residential estates around Vienna, before founding the Haus & Garten interior design firm with architects Oskar Wlach and Walther Sobotka. As early as the 1920s, Frank was critical of the austere modernism led by designers such as Le Corbusier, which emphasised industrial materials and simple, clean designs. Instead, Frank developed his own brand of modernism, one which was informed by the shapes and patterns of nature, and which emphasised comfort and hominess. He famously wrote, “Striving for total simplicity becomes pathetic. It’s pathetic that everything has to be the same, with no room for variation. The same goes for the desire to organise people and force them to become one big homogenous mass.”

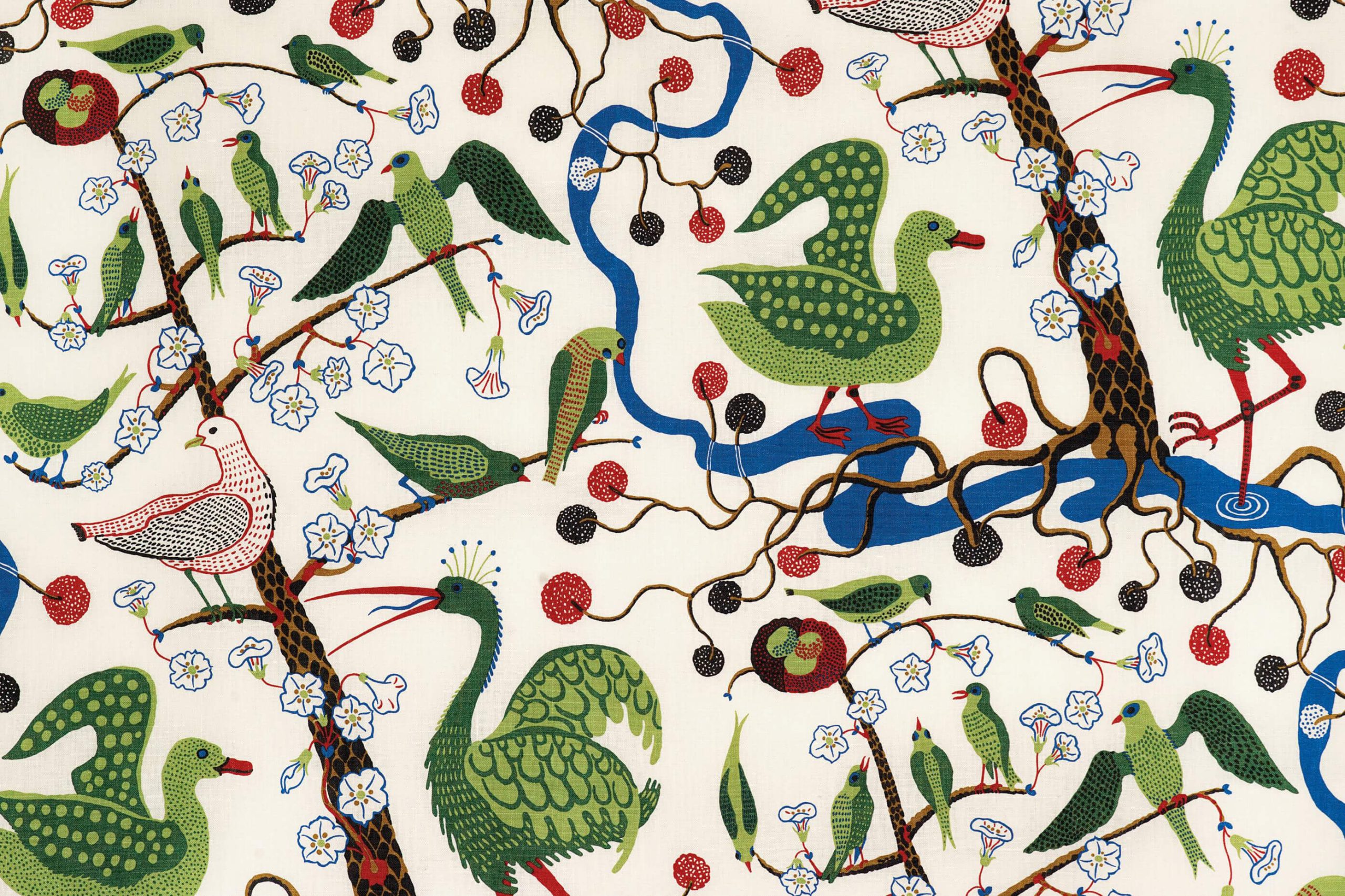

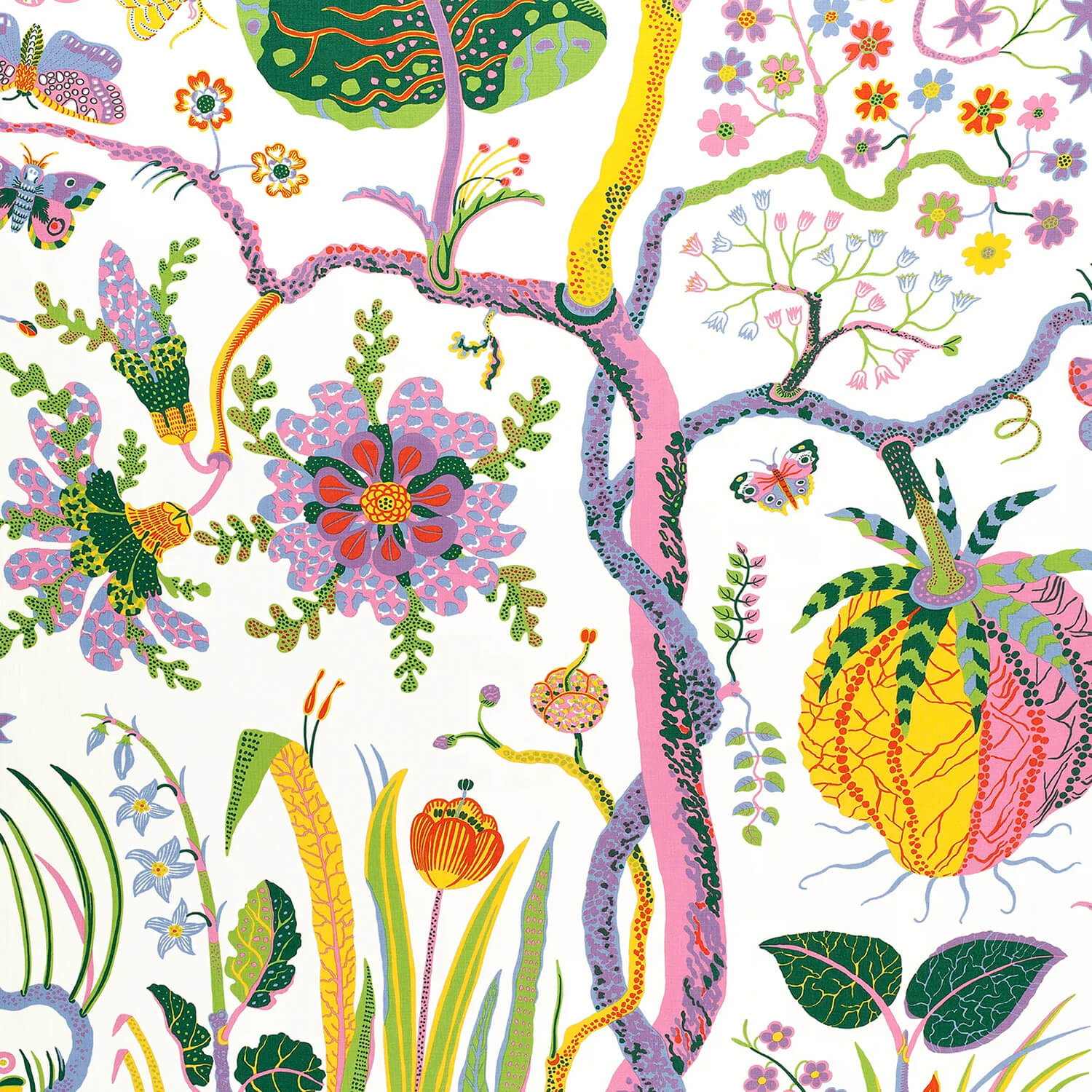

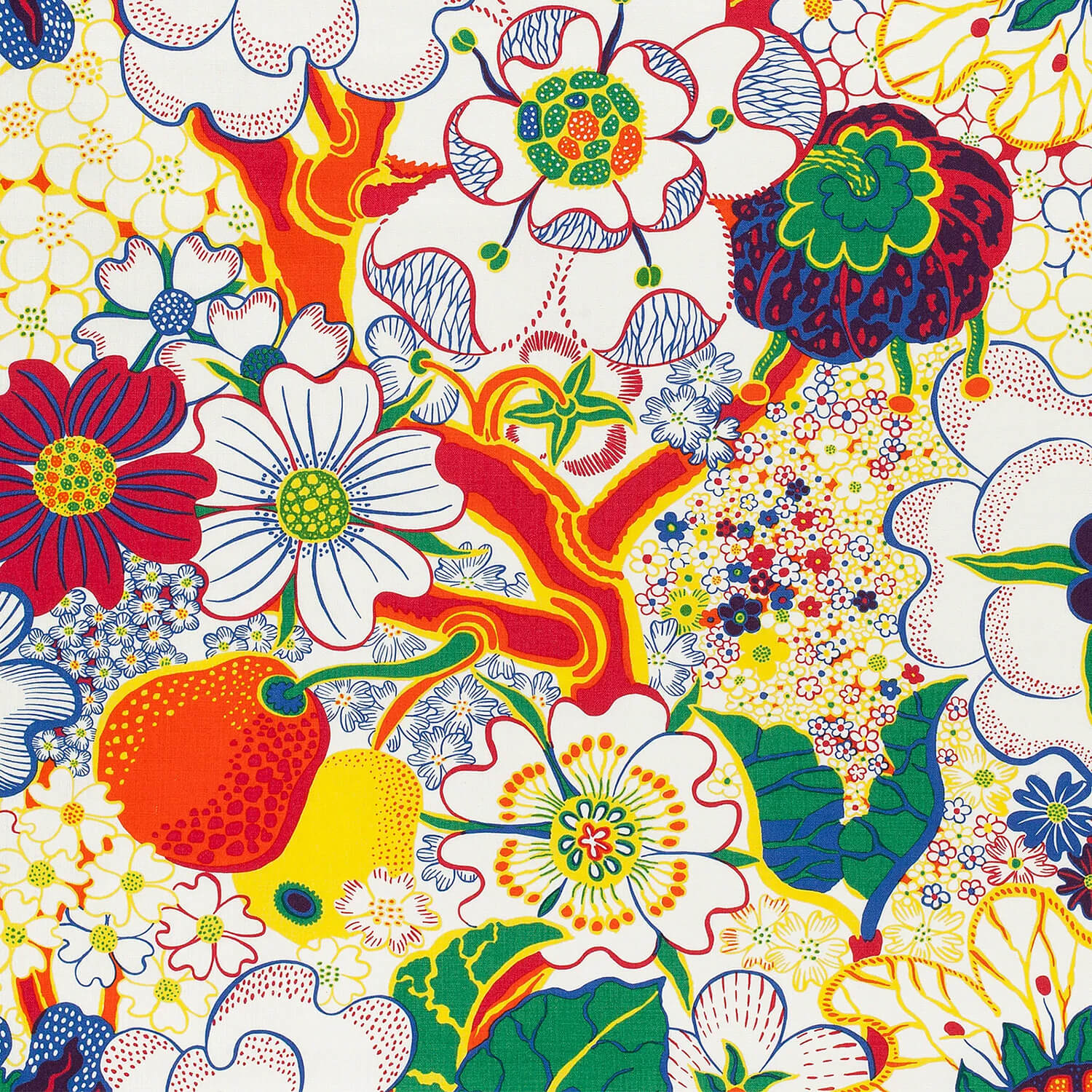

In 1933, he left for Sweden to escape Vienna’s rising political turmoil, where he began working for the furniture manufacturer Svenskt Tenn, then under the leadership of Estrid Ericson. Here he developed many of his most pioneering textile patterns for fabrics, furniture, rugs, and more. His floral patterns featured violets, crocuses, bindweed, lawn daisies, tulips, roses, and more, alongside his own fantastical flower designs, all blended together into dizzyingly complex patterns with no visible beginning or end. Frank believed such complex designs had a soothing effect on the soul, observing, “The monochromatic surface appears uneasy, while prints are calming, and the observer is unwillingly influenced by an underlying slow approach.”

Frank came to call his brand of design “accidentism”, one which is based on accident, improvisation and energy, arguing “The freer the pattern, the better”. He noted, “what we need is variety and not stereotyped monumentality.” Little surprise, then, that he made many of his most successful pattern designs by hand, painting on paper that he would twist and turn as he worked, allowing chance to define the final outcome. In one of his many essays on design, Rooms and Furnishings, he wrote, “every work of art is a puzzle… as it is the product of a process of thought that is for us unfamiliar and unfathomable. That is why we have a particular fondness for strange objects.”

During World War II, Frank fled from Europe in exile, heading for Manhattan, where he remained from 1941 to 1946. He continued to produce radical pattern designs for Svenskt Tenn during this period of uncertainty, including the patterns Teheran, Brazil, and Manhattan, the latter of which was inspired by New York City’s gridded structure. In New York he was also deeply influenced by the Metropolitan Museum’s Tree of Life motifs, which further informed the structure of his botanical inspired patterns.

Following the war, Frank returned to Sweden, where he was able to resume his pioneering textile design work up until his death in 1967. Such was Frank’s success; his work came to epitomise a style known as “Swedish Modern.” Today, many of Frank’s textile designs are still available on the market, a testament to the enduring nature of his legacy, and the endless appeal of his spirited designs.

One Comment

Ellen McPherson

Fascinating. Had never heard of him. He reminds me of Kaffe Fassett in his intricate use of pattern.