Making Tracks: The Textile Art of Igshaan Adams

Personal and collective stories about place and the need for belonging are woven tightly into the textile art of South African contemporary artist Igshaan Adams. His richly layered visual language brings together everyday ephemera from his home town, including shells, nylon rope, strips of fabric, plied cords, and beads. But it is also conceptually bound to his experience growing up in the segregated community of Bonteheuwel in Cape Town, South Africa during the 1980s, as a Creole with Malay roots, and his desire to find a place where he could feel seen, heard, and understood.

Throughout his childhood years Adams was painfully aware of the divide between Bonteheuwel and the neighbouring town of Langa. He recalls, “Growing up in South Africa being Cape coloured, I already got the feedback that I wasn’t as good as others. There was something wrong with me intrinsically.” His sense of belonging only became more complicated as he grew older, as he tried to reconcile the disparate elements of his identity. Adams explains, “Being queer and being Muslim, for instance – I just couldn’t reconcile it… And thankfully I broke free of that, though the feelings – that I’m queer, and I want to be loved, and loving, and have the full experience of being alive – never go away.”

One means of feeling grounded came to Adams through making art; he studied art and design at the College of Cape Town followed by a photography short course, and a Diploma in Fine Art from Ruth Prowse School of Art, graduating in 2009. It was a pivotal time, when as he notes, “Those early conflicts settled, and the only wish to remain was to have peace.”

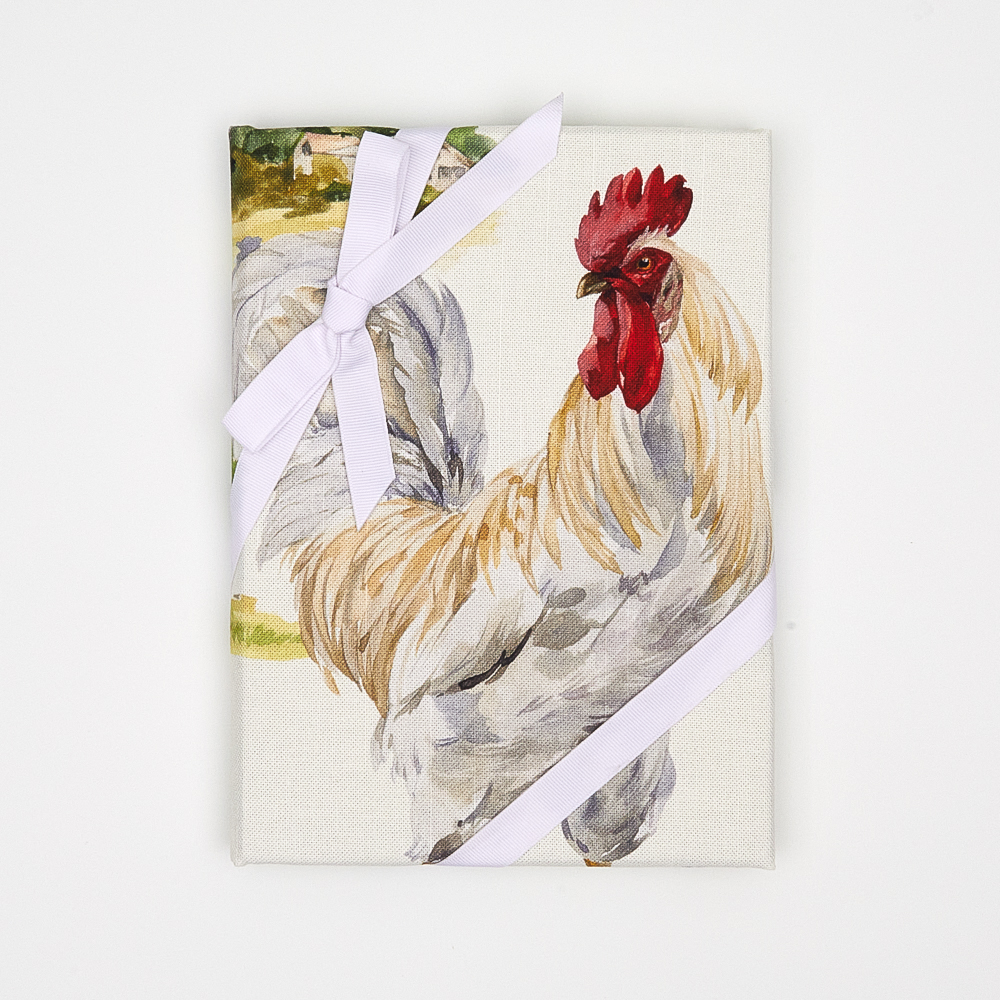

Over time, as Adams’ mature practice evolved, he developed a keen interest in maps and traces left behind by the human body on physical surfaces. One of his earliest interests was in the imprints left behind on prayer mats, which were so deeply ingrained with the spiritual practices of the individual. He subsequently began making large-scale tapestries based on the foot patterns left behind on linoleum floors, within the homes of his family, friends, and neighbours, which, he argues, become a form of intimate, diaristic cartography. Adams says, “I began seeing the floor as a map with marks and evidence of events that took place. I started using my imagination to picture what happened and what the marks meant as a document of the experiences of that particular family.”

From here, Adams has more recently made tapestries based on satellite maps documenting ‘desire lines’, or pathways made by individuals over time which deviate from the usual roads and tracks planned out for us by authorities. He explains the personal significance of the routes he has chosen, noting, “I used Google Earth to explore the area I grew up in and the neighbouring communities.” One path, in particular, piqued his interest, a secret route formed between Bonteheuwel and Langa, which had been forcibly separated throughout his youth. Adams says, “Our neighbouring community Langa had a highway that kept communities and races segregated. This pathway is the grass between the highway – it became a sign or a signal that people crossed the boundaries. It symbolises hope.”

This act of bridging gaps and coming together is also bound into Adams’ process for making art, which is part of a collective experience, rather than an individual one. He employs a team of assistants, as well as hiring members of his community, to whom he distributes his simple, rustic materials, allowing each to bring their own sensibilities into the physically demanding process of weaving. “The first thing you become aware of as you weave,” he says, “is your physicality, your body. Everything shows up… Your body needs to be elevated so you are always working at the level of your heart. Weaving takes a toll on your body so the tension in your body will show. You must have an awareness of your physical body and use it to your advantage.” As such, his final tapestries speak of community in both form and concept, breathing with a freshness and vitality that is innately bound to the artist’s entire lived experience, and the place he has come to belong.

3 Comments

Msapir13@gmail.com Sapir

Fascinating work. I’d be interested to know more about his techniques.

Arlene Mead

Amazing work by an artist I was unfamiliar with!

Thank you for all of the great articles about artists. ?

Emily Ulrich

Absolutely stunning. What a talent! Thank you for making me aware of this fine artist.