The First Lady of Weaving: Else Regensteiner

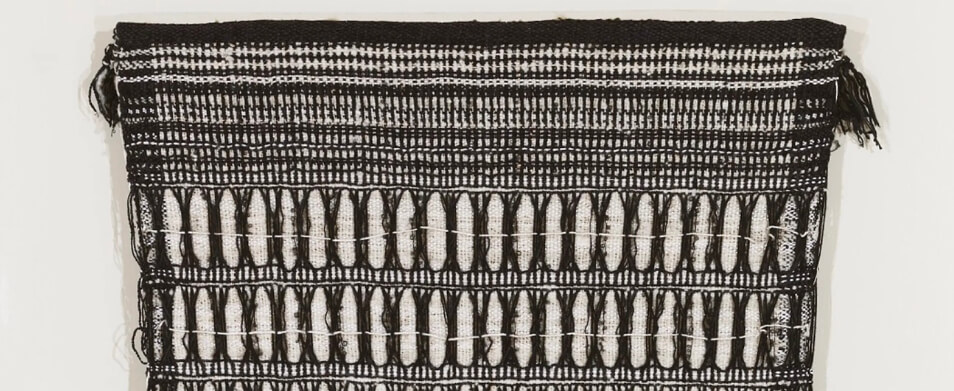

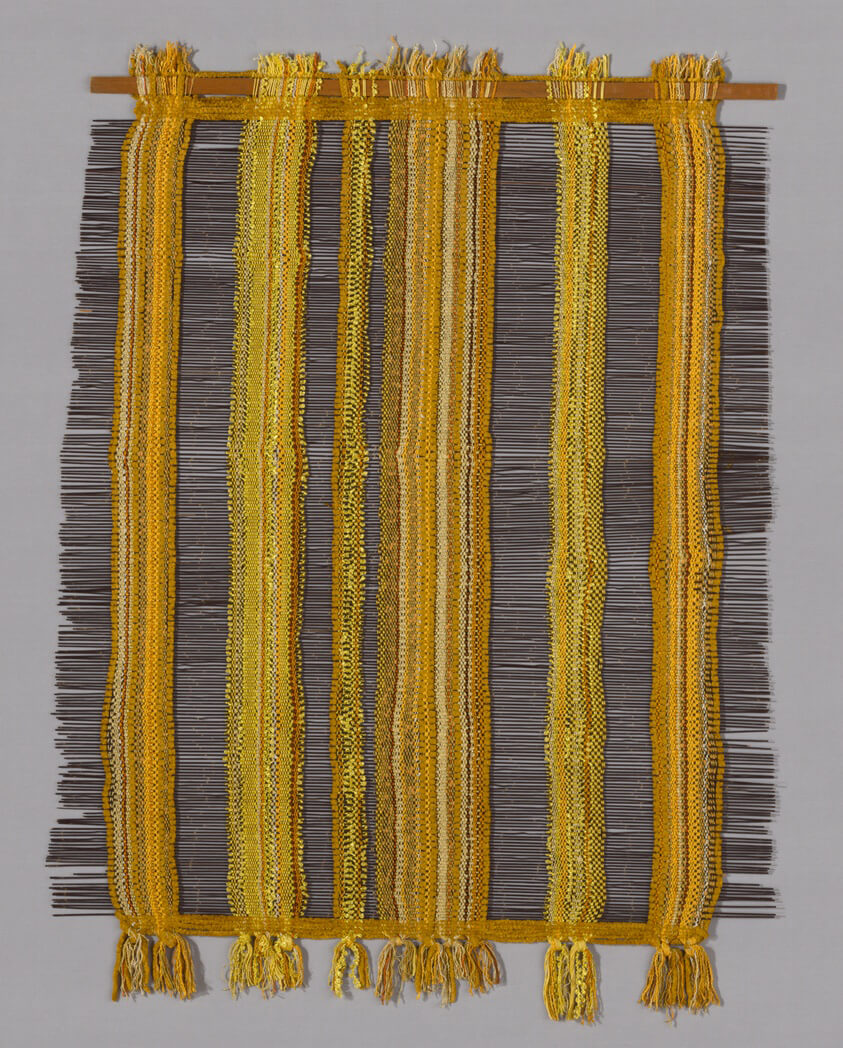

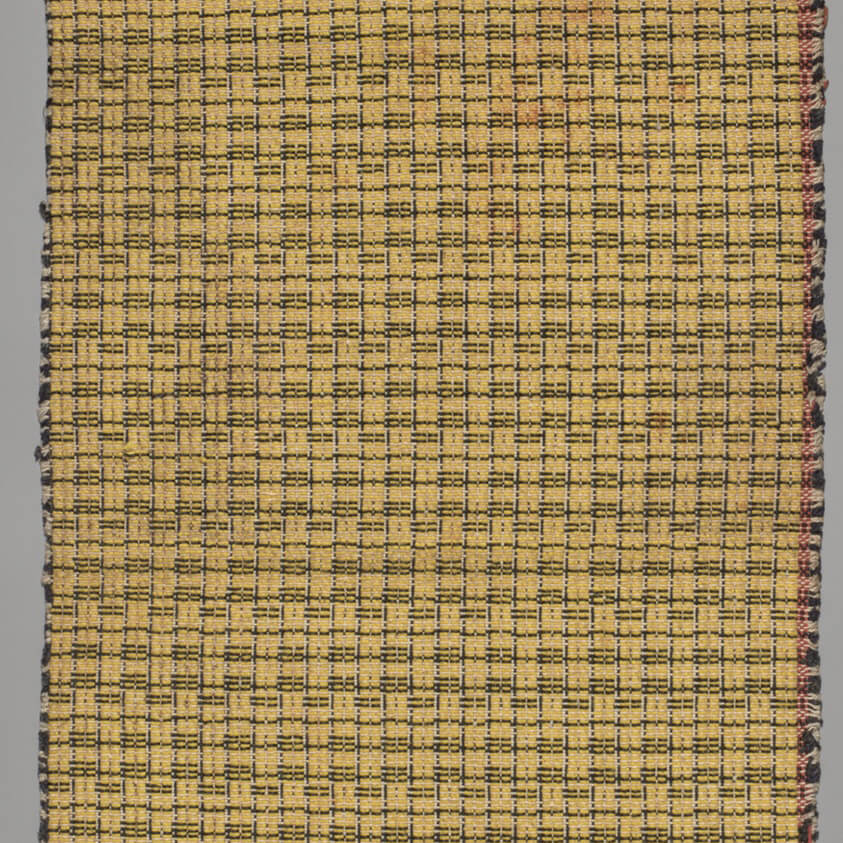

Known collectively as the “first lady of weaving,” world-renowned German-American weaver Else Regensteiner was one of a generation who brought a Bauhaus sensibility for weaving-as-art into the American cultural landscape. As well as producing striking weavings that experimented with unconventional and unexpected patterns, colours and materials, she was also hugely influential as a teacher, writer and lecturer, celebrating the wondrously creative artistic freedom that she found through producing textiles of all shapes and sizes.

Born in Munich, Germany in 1906 as Else Friedsam, she studied at Deutsche Frauenschule in Munich, earning a teaching degree in 1925. In 1926, Else married Bertold Regensteiner, and they had a child together in Germany, before emigrating to the United States in 1936. After befriending the former Bauhaus weaving school graduate Marli Ehrman, who was running the weaving workshop at the New Chicago Bauhaus (later the Art Institute of Chicago), Regensteiner took up a job with her as a weaving assistant, arranging to learn the practice of weaving along the way.

Ehrman had a profound influence on Regensteiner, teaching her how to draft and weave on a fly shuttle loom along with introducing her to the Bauhaus school and the phenomenal work that had been made in the weaving department. Following on encouragement from Ehrman, Regensteiner went on to study weaving at the legendary Black Mountain College, where she was taught by both Anni Albers and Josef Albers, both former faculty members of the Bauhaus.

Following graduation, Regensteiner returned to Chicago where she slowly built up a monumentally successful career as both a teacher and weaving master in the decades to come. Her first teaching post was at the Jane Addams Hull House, a social settlement in Chicago where she had her first studio space. In 1945, Regensteiner began teaching evening classes at the New Bauhaus School where she had formerly worked with Ehrman. From evening classes, she worked her way up to becoming assistant professor in the school of fibre arts, and later full professor in 1947. Regensteiner was also an avid traveller, and she gave charismatic and memorable lectures on the art of weaving across the US and Canada. In 1957, she became director of the school’s weaving department, where she remained until retirement in 1971.

Alongside her teaching work, Regensteiner founded the Reg/Wick Hand Woven Originals weaving studio along with Julia McVicker during the 1940s. Together they created a huge range of custom made, handwoven fabrics for architects and interior designers across the United States, along with a series of prototypes for industrial production lines, thus continuing the Bauhaus ethos for taking art into industry. Regensteiner became particularly well known for emphasising innovation through the integration of non-woven materials including leather into her fabrics, giving them a richly tactile and three-dimensional, sculptural quality. Reg/Wick subsequently won numerous design awards and had their work featured in a series of exhibitions across the United States, which was instrumental in paving the way for the Fibre Arts movement of the following generation.

After retiring from teaching, Regensteiner showed no sign of slowing down; she became a weaving and design consultant at the American Farm School in Thessaloniki, Greece for the next five years and served on the board for the Handweavers Guild of America until 1976. Such was her widespread influence, in 1980, the Midwest Weavers Association established the Regensteiner Award, to honour others who have made a significant impact on the practice of weaving.

Throughout 1970s and 1980s Regensteiner wrote numerous books on weaving, including The Art of Weaving, 1970, Program for a Weaving Study Group, 1974, Weaver’s Study Course: Sourcebook for Ideas and Techniques, 1982, and Geometric Design in Weaving, 1986. By the time she passed away in 2003, her legacy was vast; her seeds had now been cast throughout much of the United States and beyond, carried by the students, readers, buyers and listeners who absorbed so much from the talents and gifts she shared so freely with the world.

One Comment

J S

I was a young student of weaving in the 1980s, and an avid devote of the fiber arts before and since, always. Your article has inspired me. It may not be my career path, but think I need a weaving loom in my life again.