The Bauhaus Innovator: Otti Berger’s Textiles

Bauhaus textile artist and weaver Otti Berger was one of the greatest innovators of her generation, producing a dazzling array of complex and intricate fabrics that have inspired generations since. During her time as a student and later a teacher with the legendary German Bauhaus school she was endlessly inventive, experimenting wildly with weaving methods and materials to create striking designs that pushed fabric production into unchartered territory. Though her life was cut tragically short, she played an instrumental role in elevating textile production to the same status as fine art, proving it could hold equal weight in a gallery alongside other art forms. She wrote, “Fabric can be understood through the hands as much as a colour through the eye or a sound through the ear.”

Berger was born in 1898 in the town of Zmajevac in the Baranya region of Austria-Hungary, now in present-day Croatia. The region was known for its rich textile traditions, which most likely influenced Berger’s desire to pursue the practice. She studied at Collegiate School for Girls in Vienna, followed by Royal Academy of Fine Arts, University of Zagreb. In 1927, she moved on to the introductory course at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, where she trained with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky.

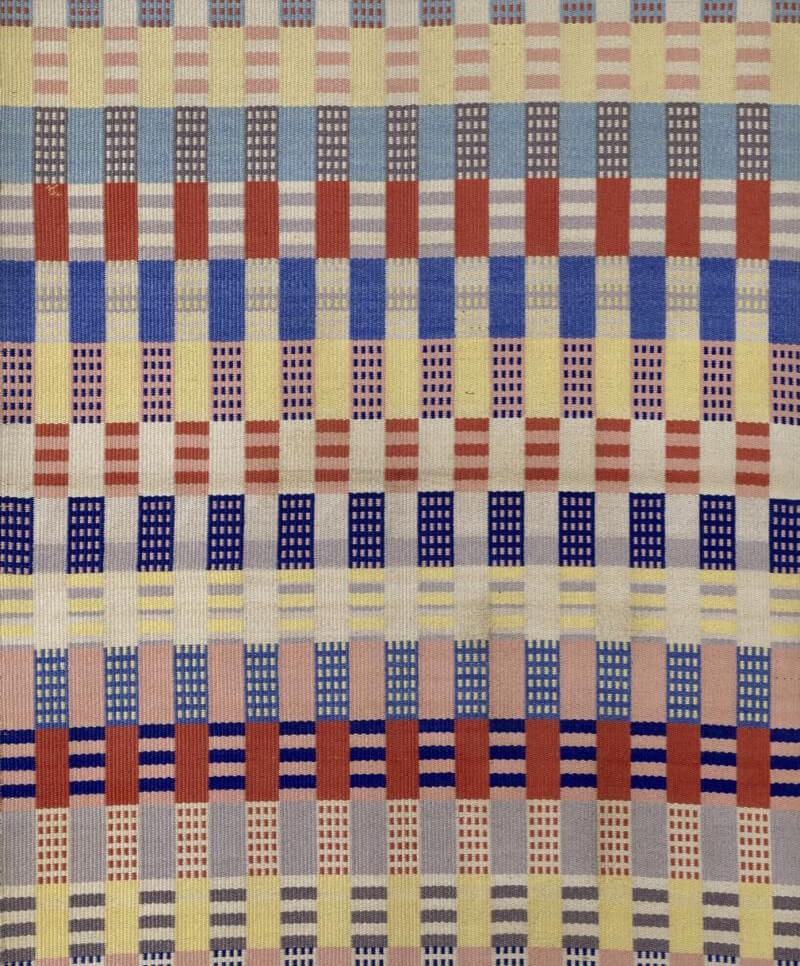

A year later Berger enrolled in the weaving course which was then being run by renowned weaver and teacher Gunta Stolzl. At this stage in Bauhaus history, weaving students were being taught how to produce textiles that would fit in with functionalist architecture, adding depth, weight and substance to austere modernist interiors. It was a formative time for Berger when she developed a signature style composed of abstract geometric patterns and vivid colours along with artificial materials including cellophane, viscose, rayon and cellulose, which, as she discovered could add glossy, light reflecting passages to her tapestries. Looking back on her years at the Bauhaus, she wrote, “To become an artist, one has to be an artist and to become one when one is already an artist, then one comes to the Bauhaus, and the task of the Bauhaus is to make a human being of this ‘artist’ again.”

In 1929, Berger spent time studying textiles in Stockholm and Norway; she was particularly taken with Norwegian traditional textiles, composed of simple geometric patterns and earthy colours, which came to shape her work on her return to the Bauhaus. One of her breakthroughs during this time was twill weaving, which she made by blending wool or cotton with viscose and ramie. During this time Berger gave a series of public interviews and wrote numerous articles on weaving, which played a vital role in elevating fabric into a significant art form.

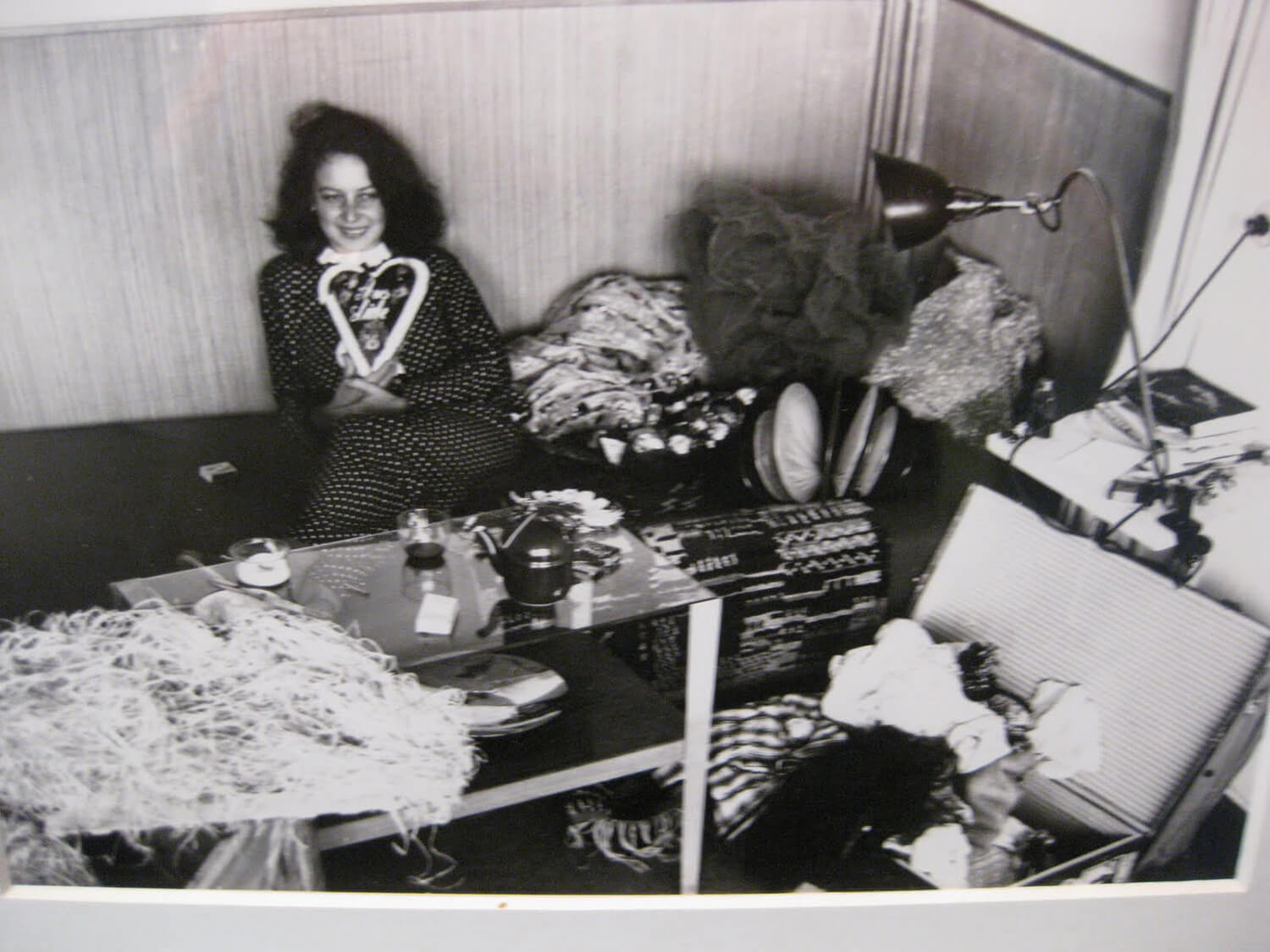

Following graduation Berger took on teaching work at the Dessau Bauhaus, working her way up to become the deputy in textile workshop under Lilly Reich, and head of the weaving workshop in 1931, remaining here until the school was forced to close in 1932 under Nazi rule. From here she went on to establish her own weaving studio in Berlin, where she was incredibly prolific, designing textiles for various industries and interiors, including the textile company De Ploeg in the Netherlands, and the interior design company Wohnbedarf AG in Zurich. As well as managing to secure patents for her designs, Berger also branded her textiles with her name, raising the status of designers in what had predominantly been an anonymous industry.

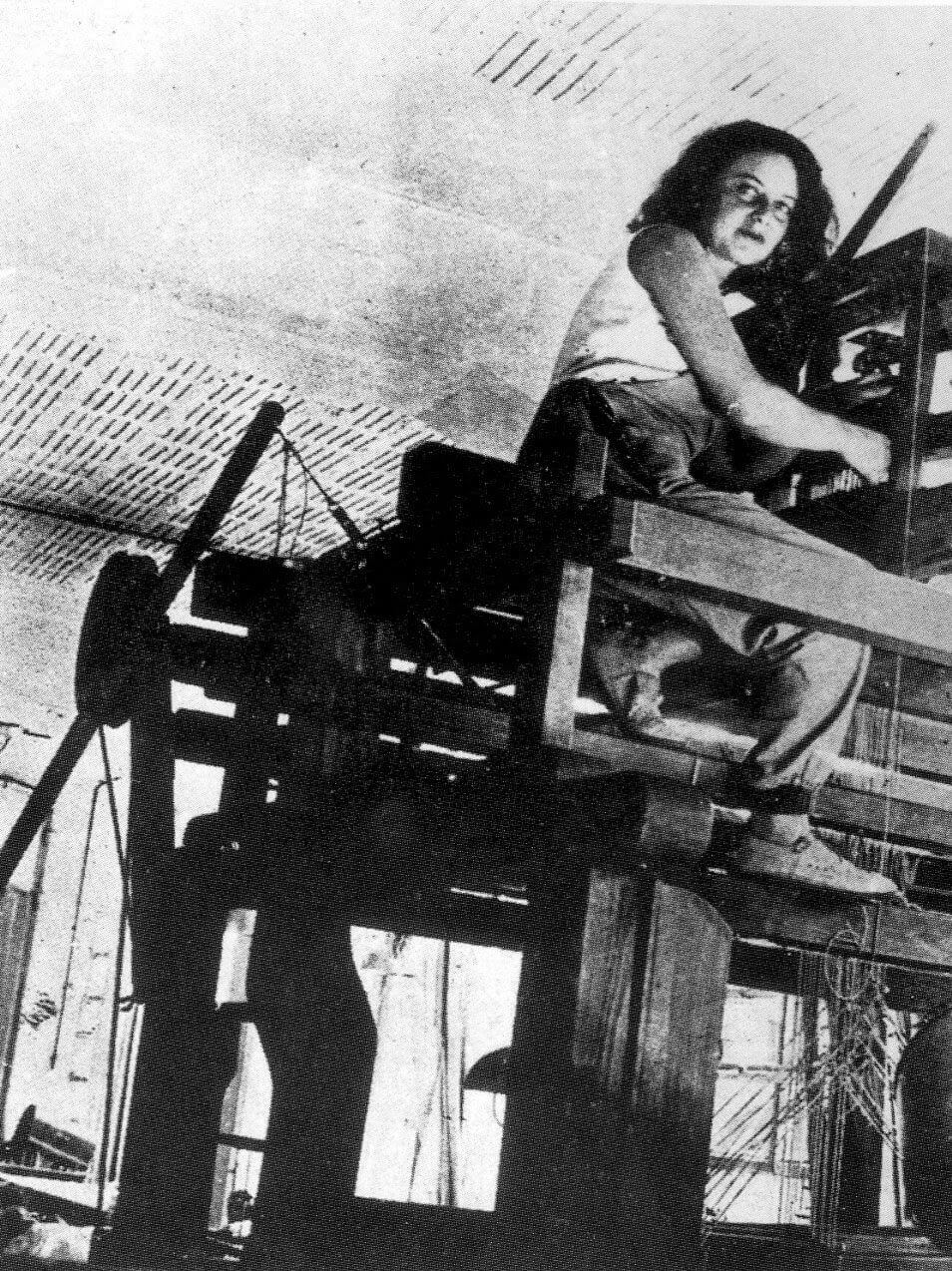

But it was Berger’s practice of weaving on a loom without pre-planned drawings that fully demonstrated her inventive, artistic spirit in full force. She wrote in a letter to a friend about a weaving she was working on during the 1940s, “I have not made any preparatory drawings – nor followed a pattern. In this way I am not restricted, and besides, working from drawings is not my thing… I simply know what I want, and sometimes I dictate and sometimes the rug does…”

Sadly, Berger’s Jewish family status in Nazi Germany made her place in Germany increasingly fragile. She fled to London to escape persecution, even though she spoke little English, and struggled to find steady work. After unsuccessfully trying to gain access to the United States where many of her colleagues had found refuge, Berger made her way back to Zmajevac to care for her elderly mother. But tragically she was deported along with her family to Auschwitz concentration camp in April 1944, where she died. This meant Berger was unable to live out the same years of expansion and unbridled freedom as her contemporaries including Anni Albers and Gunta Stolzl, which has, perhaps, made her name less well-known. Yet in her short life she was able to leave behind a substantial body of work that spanned weaving as art and weaving for industry, making great leaps and bounds into both arenas, while proving they aren’t so different after all.

4 Comments

Nilda Lehmann

Thank you so much for keeping Berger’s passion alive.

I always enjoy learning from your articles.

Nilda

Susan Leftwich

Thanks for always having interesting stories of textile artists. This one is sad. Are there any remains of her work in museums in the world?

Vicki Lang

Even though I don’t always comment of your articles I love to read them. You always have such fascinating people with wonderful art talents. Thank you for the knowledge of such awesome people.

Thomas Meek

Thank you for this excellent short biography of a person who had an enormous influence on the progress of 20th Century fabrics design. Your style is clear, informative and very smooth and almost poetic to read.

I always learn a lot when I ready our pieces.

Good wishes, and success to you!

Thomas