Off the Wall: Claire Zeisler

A self-proclaimed ‘late developer,’ fibre artist Claire Zeisler hit her stride during the early 1960s when she was nearly 60 years old, taking the United States art world by storm. Along with her contemporaries Lenore Tawney and Sheila Hicks, Zeisler became an outspoken, radical pioneer in the Fibre Art movement, taking the historical tradition of weaving off the wall and into three-dimensional space. Having studied with numerous former Bauhaus artists who had emigrated to the US, Zeisler is widely recognised as a post-Bauhaus pioneer, who integrated the same experimentation with texture, pattern, colour and form of her European counterparts into her practice, while taking their ideas into bold and unchartered new territory.

Zeisler was born in 1903 in Cincinnati, Ohio, as Claire Block. She studied briefly at Columbia College in Ohio before marrying her wealthy first husband, Harold Florsheim, heir to Florsheim Shoe, and raising their three children. During the 1930s Zeisler began a love affair with art, amassing a huge private collection which included masterpieces by Paul Klee, Joan Miro and Henry Moore, along with various artefacts including ancient Peruvian textiles and American Indian baskets. Following her divorce from Florsheim, she married the physician and author Ernest Bloomfield Zeisler.

During the 1940s as her children grew older, Zeisler became increasingly drawn to the creative arts. During this decade she studied at the Chicago Institute of Design, formerly known as the New Bauhaus, along with the Illinois Institute of Technology. In 1946, she attended the Summer Art Institute at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, studying color and design under Josef Albers. It was a formative period for Zeisler, when she began working with three dimensional materials in abstract and experimental ways alongside a like-minded group of peers. Zeisler recalled, “At a certain time in history people experience the same development and respond to the same stimuli. They find parallel ways to express themselves, whether they communicate directly with each other or not.”

During this time Zeisler learned to weave from her friend Bea Schwartzchild, who told her, “…if you knew something more about the technique of the loom, I think you could go places.” Her training with Schwartzchild was focussed on what Zeisler called “All technical problems,” such as “how to dress any loom… the right number of threads to the inch for the size of your threads… and the right weft to use so that there’s a nice balance, so that your material doesn’t come out sleazy and so on, so forth.”

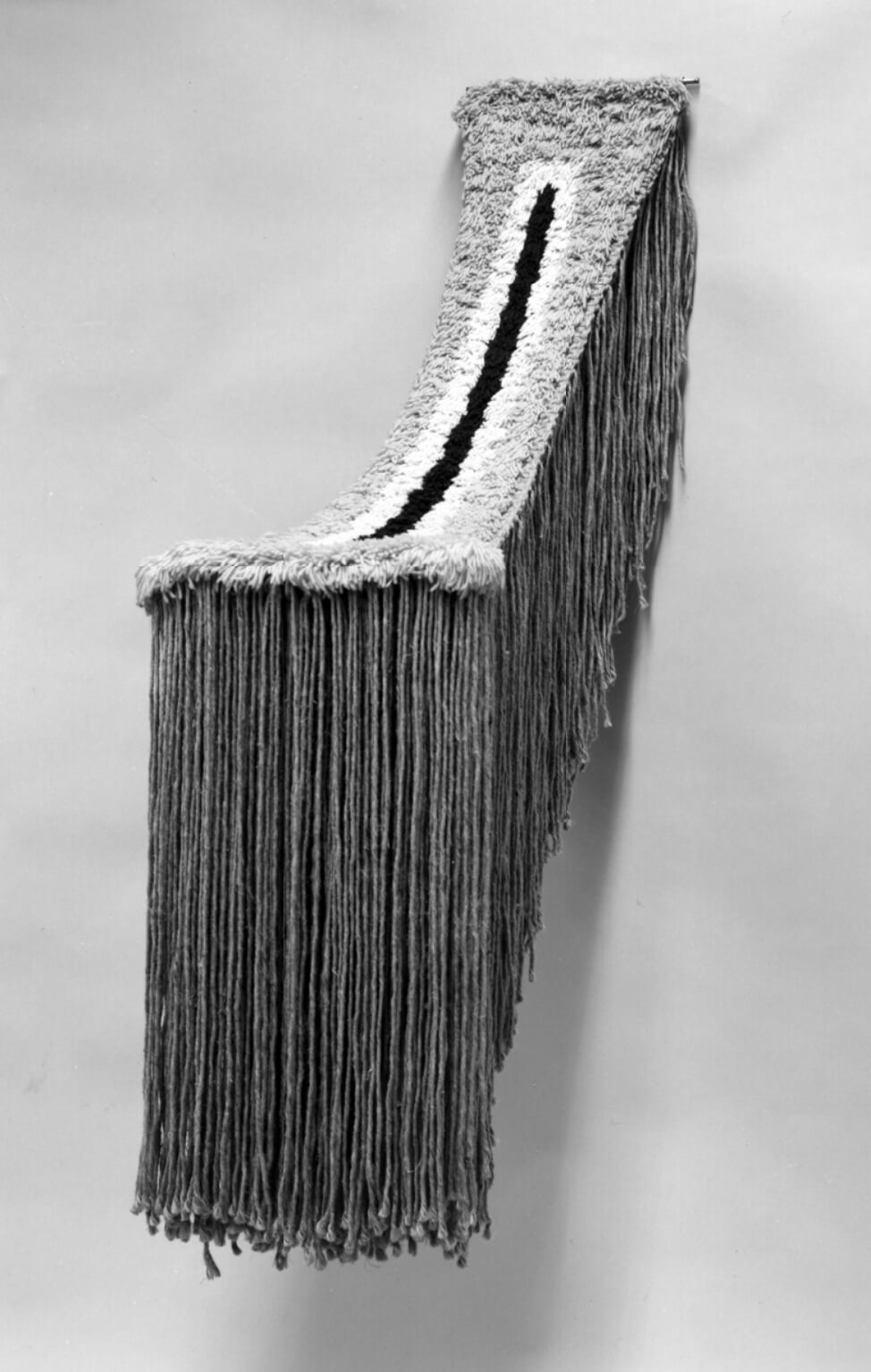

Zeisler spent much of the 1950s learning how to weave, making a series of practical, useful items on a loom at home, “modest weavings for table place mats and apparel fabrics,” as well as suiting material for her second husband’s work wear. But by the end of the decade, she had moved on to making individually weaved wall hangings designed to be hung on the wall akin to abstract paintings. In these early weavings, Zeisler drew influence from Haitian, African, Native American and Oriental Art, re-examining the hand-crafted items she had collected decades earlier.

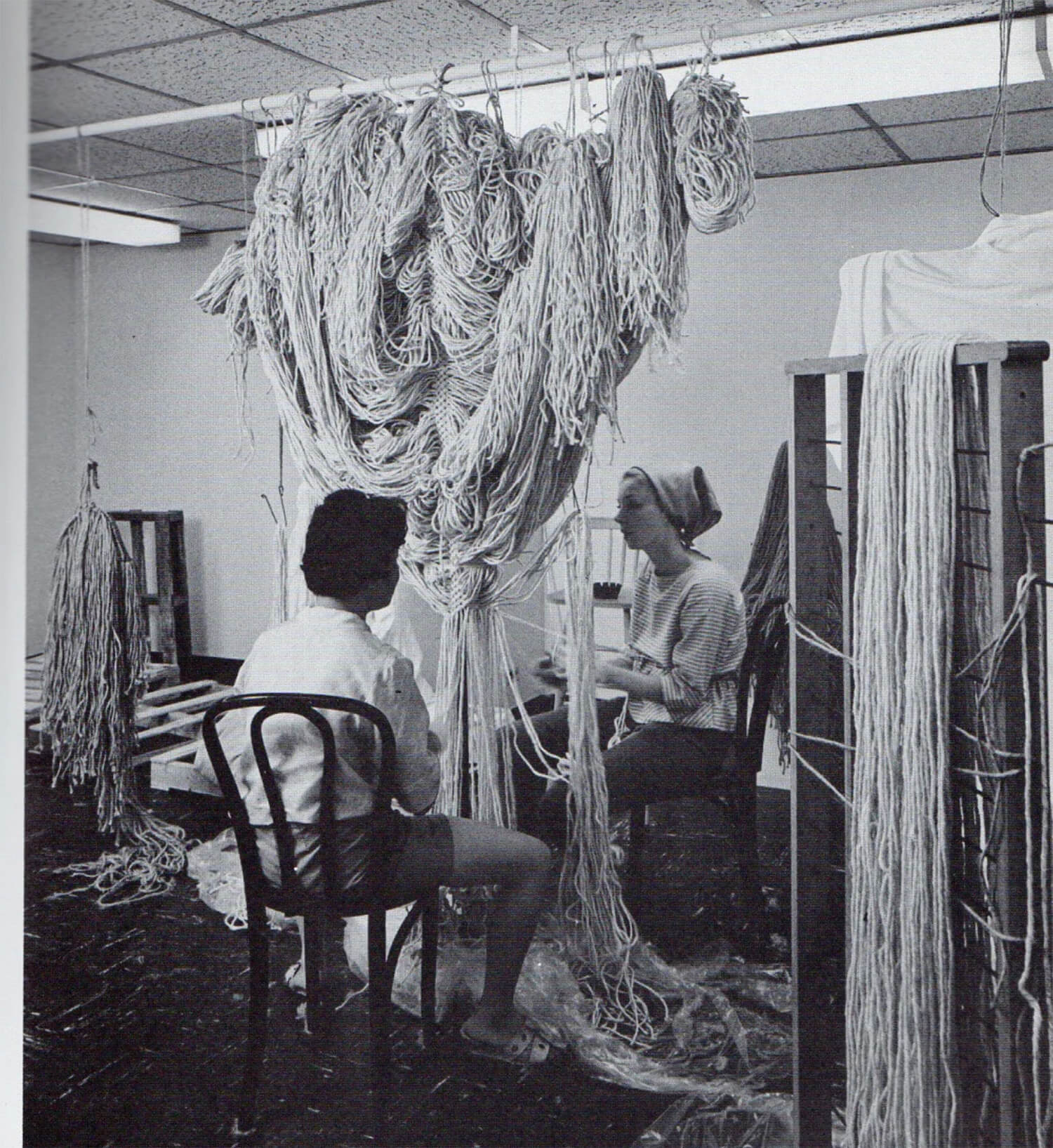

Having mastered the technique of weaving by the early 1960s, Zeisler was ready for a new challenge. In line with her Fibre Art contemporaries Lenore Tawney and Sheila Hicks, Zeisler began toying with how to take weaving off the wall and into three-dimensional, sculptural forms through the use of various combined techniques, including loose knotting and free-falling threads. In a 1979 interview for the Chicago Tribune she said, “I gave up weaving in 1961. The loom was too limited, and I took up a knotting technique that was very free, allowing for many variations.” She explained further, “Most people would call the technique macramé, but that is a series of decorative knots that is left visible in flat patterns… I use the knot as a base, the way the painter uses a canvas… The knots are used only to make my work three dimensional, sculptural. You do not see them at all.”

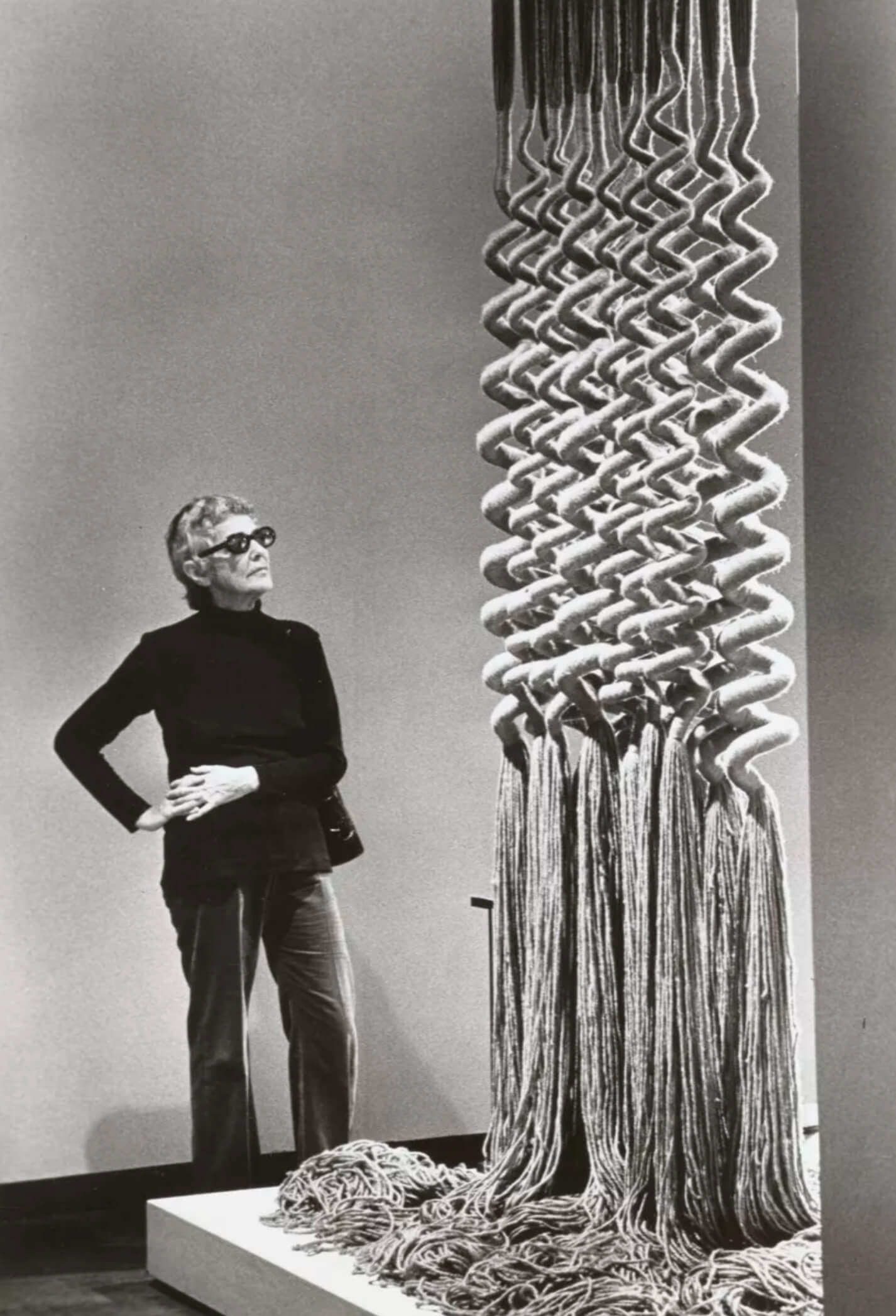

Monumental in scale and featuring passages of daringly bright hues including tomato red and golden yellow, her sculptural weavings had a commanding physical presence that invited widespread public attention, leading to a series of high-profile exhibitions and displays. Throughout the 1970s Zeisler continued to experiment freely with fabrics and threads in three dimensions, producing vast armatures and small, intricate woven objects. She toyed with folding and plaiting leather, stacking cotton and wool into totemic forms, or playing with how loose strands of textile could spread out across the floor in unruly tangles.

Zeisler’s place in history was cemented by two major retrospectives – one at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1979, followed by the Whitney Museum of American Art New York in 1984. By now widely accepted as an innovator in her field, Zeisler’s work undoubtedly opened the floodgate for daring new approaches in textile art, with a practice that was full of unexpected, unconventional elements. Her influence can be seen in artists working in various disciplines, from the monumental sculpture of Anish Kapoor to the textile art of Josh Faught. She said, “I am interested in investigating… ways to create textiles which are not only aesthetically pleasing because of design and colour, but also contain… tactile and visual surprise, pleasure, excitement.”

One Comment

Riquee Wilson

Awesome article!