Art into Industry: The Tactile Textiles of Gunta Stölzl

German textile artist Gunta Stölzl was a remarkable early 20th century weaver with an innate sensibility for the sensuous, tactile qualities of weaving. Her fantastically complex designs are a true feast for the eyes, and even today appear remarkably fresh, with their dizzying geometric patterns, shapes and colours that seem to buzz and hum with life. Anni Albers, Stölzl’s student at the Dessau Bauhaus during the 1920s, described how her teacher had an “almost animal feeling for textiles,” one which was to have a profound impact on a generation of weavers, and indeed artists, to follow.

Born in Munich in 1897, Stölzl’s diaries reveal how her early life was filled with mountaineering adventures and studies in philosophy and literature. She trained in the arts at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Munich between 1913 and 1916, learning skills in glass painting, ceramics and decorative painting, as well as producing countless sketches of the people and places around her. Stölzl worked for a year during the First World War as a Red Cross nurse, during which time she continued to fill sketchbooks with drawings and ideas.

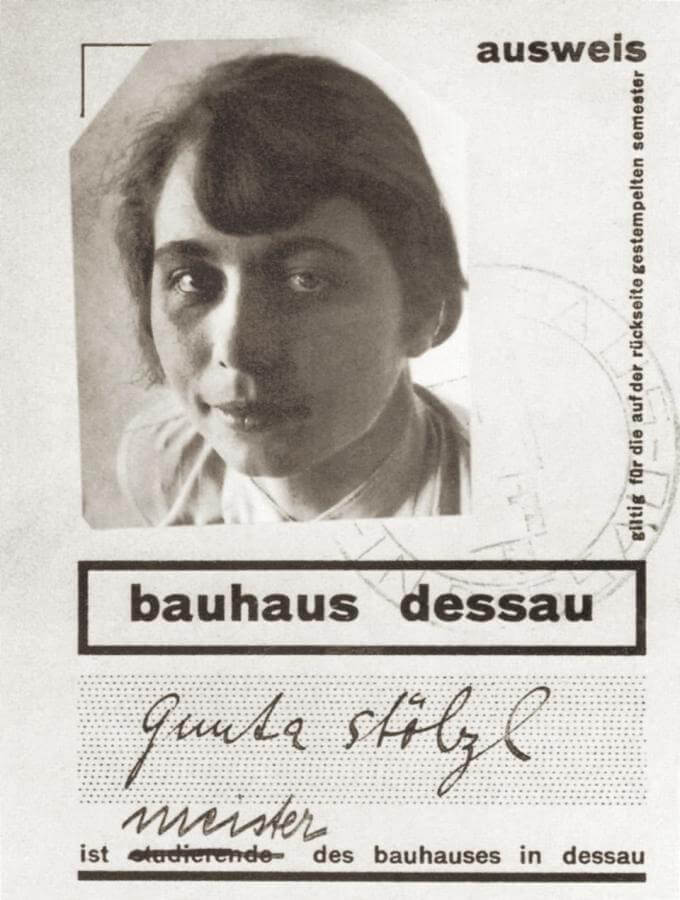

But it was in 1919 that the course of Stölzl’s life began to take shape, when she enrolled as a student at the Weimar Bauhaus. Recalling the freedom she found as a student of Johannes Itten here, she wrote: “Itten doesn’t want to teach us how to paint or draw or make art – nobody can do that. Instead, he simply wants to take us to the point where we will free ourselves.” Stölzl had originally hoped to train as a painter, but like all female students, she was instead pushed into what was considered ‘women’s work,’ the decorative fields of weaving, glassmaking, and bookbinding. However, within the weaving school Stölzl found an unexpected freedom, a space where she could condense her complex world of ideas into richly tactile works of art.

Group portrait of Bauhaus masters, from left to right: Josef Albers, Hinnerk Scheper, Georg Muche, László Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Joost Schmidt, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Gunta Stölzl, and Oskar Schlemmer, 1926

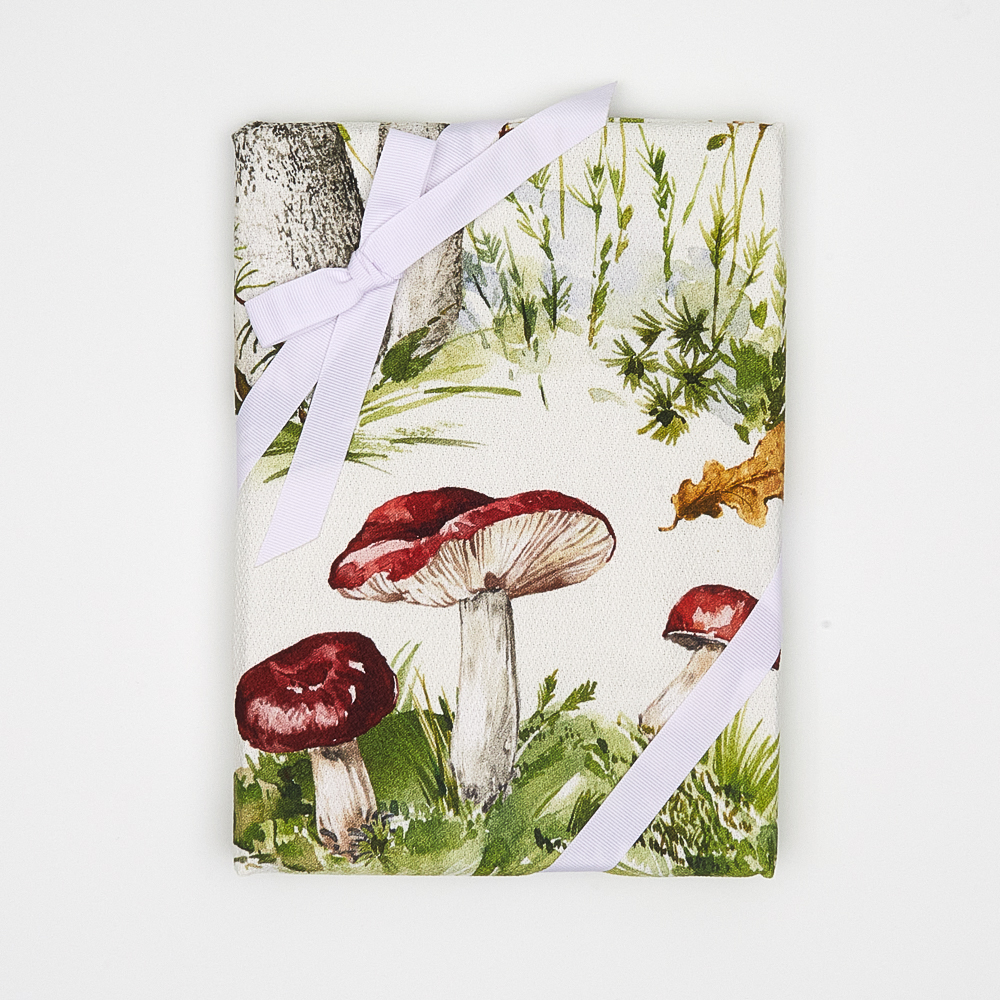

From 1923 onwards Stölzl began making her first weavings on a flatweave loom, which would become boldly decorative wall hangings, knotted carpets, and blankets. These early works demonstrated the impact of the Bauhaus teachers Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, with vibrant, patchwork designs based on her extensive drawing work. After several years spent developing her weaving practice, in 1925, Stölzl joined the Bauhaus, now in Dessau, as head of the Weaving Workshop, a role that would become life-defining.

Under her tutelage, a school of female students were encouraged to experiment freely with hand-woven designs, which then became prototypes for large-scale, industrial design. She encouraged her students to invest aspects of poetry, rhythm and musicality into their designs, which could then light up the architectural spaces, pieces of furniture, or living bodies they came to inhabit as fabrics. Subsequently, her workshop became the busiest and most profitable strand of the entire Bauhaus, as commission after commission rolled in. President of Designtex, Susan Lyons notes how the Weaving Workshop became “the embodiment of what the Bauhaus was supposed to be, taking things down to an abstract form and turning them into products.”

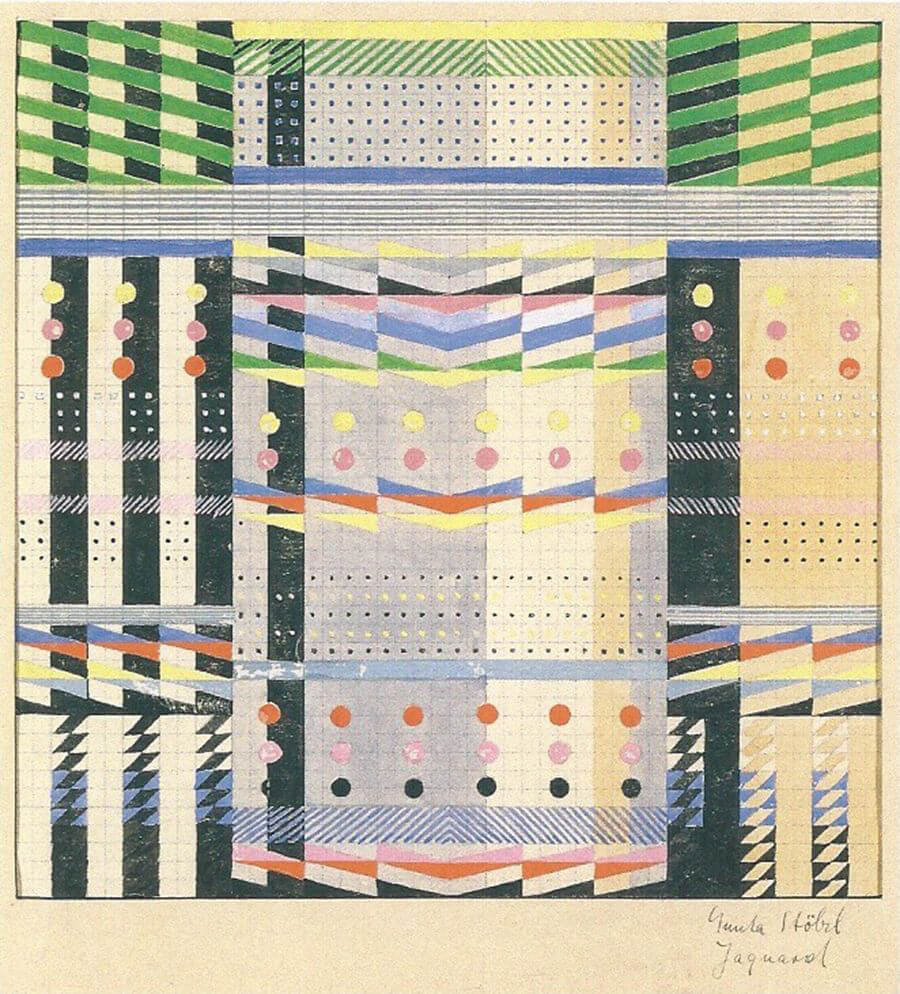

As well as expanding her repertoire as a teacher, Stölzl continued to develop the scope of her weaving practice. During the late 1920s she explored working with a Jacquard loom, producing a series of beautifully complex, intricate wall hangings. As political instabilities arose in Germany during the following decade, Stölzl was forced to resign from the Bauhaus. Instead, she moved into the realms of design for industry.

With her fellow staff members Getrude Preiswerk and Heinrich-Otto Hurlimann, she established the weaving mill in Zurich titled S-P-H Stoffe (S-P-H Fabrics). Later, the company evolved into S+H Stoffe, shared between Hurlimann and Stölzl, followed by Handweberei Flora (Flora Handweaving Mill) which Stölzl ran alone. Each iteration of the prolific company made a huge range of weavings on commission for curtains, furniture, wall tapestries, coat and dress fabrics and more. One of their greatest innovations included the development of cellophane fabrics for the Urban cinema and the Corso theatre in Zurich.

During the late 1960s – while in her 70s – Stölzl gave up the commercial business in order to focus on the hand-weaving techniques that had played such a fundamental role in her early years. She found great acclaim during this late period of her career, taking part in a series of regular exhibitions and producing work regularly for private collectors, thus carving her place in history an artist of great ingenuity and invention.

One Comment

Peggi Laubenheim

Thank you Rosie for a very interesting article on Gunta Stolzl, I feel like I’m getting an art history lesson from the articles that you write on this site. It’s good to see how many women have been successful in pursuing a career in the textile arts.