Georgiana Houghton: The Victorian Visionary

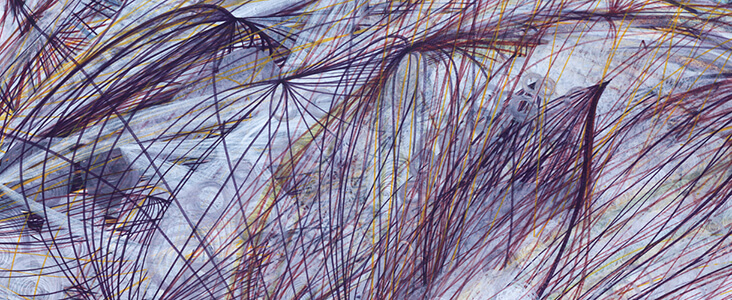

Swirling lines move through Georgiana Houghton’s art like loose threads or tangled masses of unruly hair. Now and again eyes or faces peep through their midst, meeting ours with a deep, penetrating gaze. A visionary artist and medium with remarkable foresight, Houghton pioneered an expressive language of abstraction that was well before her time. So much so, many argue it is Houghton who was the first ever abstract artist, who delved deep into metaphysical, spiritual and subconscious worlds long before her male contemporaries caught up. In her day she earned critical attention and praise, but as is the case with so many female artists, her name became lost through the sands of time.

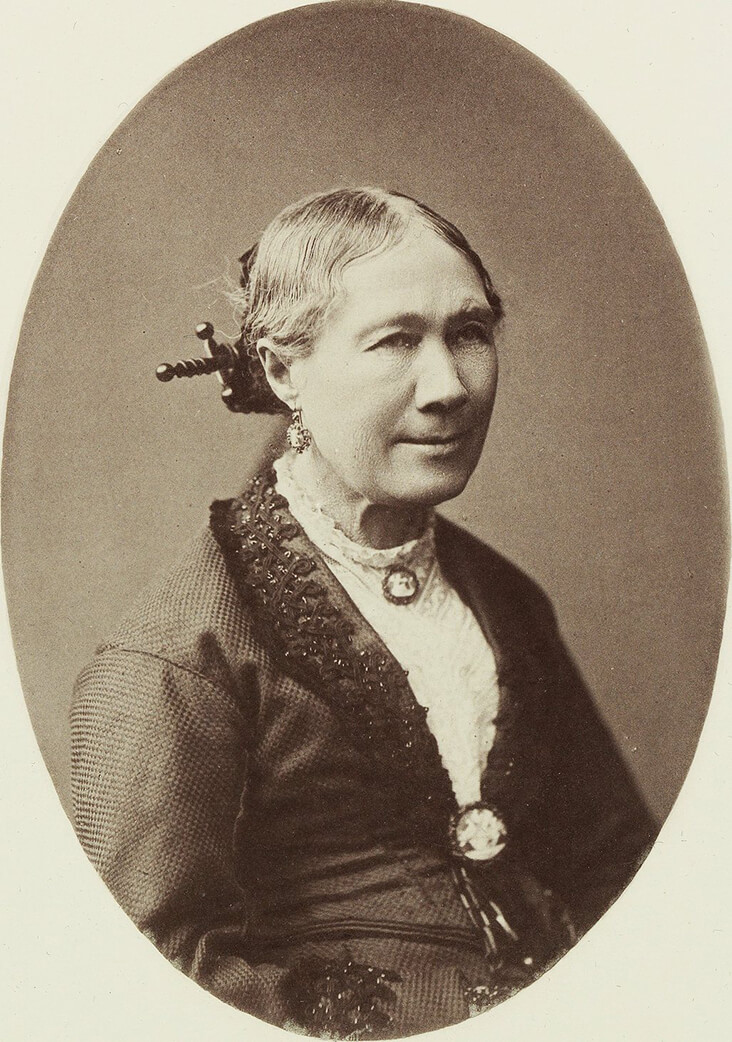

Not much is known about Houghton’s early life and artistic training. We do know, however, that she was born in 1814 in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, one of 12 children. Houghton grew up predominantly in London, but she travelled frequently due to her father’s work as a merchant. Her early art reveals an inclination towards flowers and plants depicted in watercolour, which became increasingly surreal over time, and because of this it seems likely that she trained as a botanical artist at some point in her early adulthood. After losing her sister, Houghton became increasingly entrenched in her Christian beliefs about life after death.

In Victorian Britain the rising fascination with spiritualism piqued Houghton’s interest enough to draw her to a séance at the home of a well-known medium Mrs. Mary Marshall in 1859. The experience profoundly shook Houghton, and from this point onwards her interest in communing with spirits became an enduring obsession. Houghton trained as a medium herself, and she firmly believed that she could communicate with voices from beyond the grave. Her art became a manifestation of these conversations, an outlet which allowed her to visually express the transcendental emotions she felt rising up within her.

It is plain to see from her art made throughout the following decades that Houghton was an artist of formidable talent, with an extraordinary and unique vision. Her ability to blend fluid sensations of light and movement with rich and complex colour schemes through watercolour and drawing have resulted in some of the most compelling images of the modern era. Elements of figuration emerge here and there, many of which make reference to the Holy Trinity; Houghton thought connecting with the spirit world through art could bring her closer to God. Looking back, it seems hard to believe that Houghton made such radical breakthroughs even before the Impressionists had hit centre stage in the eye of the public. Even more surprisingly, Houghton claimed she was not the author of her own art, attributing her work to deceased family, ‘invisible friends’, and even distant artists from the Renaissance, who she argued channelled their own work through her mind and body.

Understandably, critics in her day questioned Houghton’s sanity, suggesting she was not of sound mind. But one particular lengthy interview with a doctor following a group séance proved she was entirely well. Over time Houghton became quite the socialite, mixing with many other high-profile mediums and spiritualists. In 1867, Houghton was even invited to give a lecture at the opening event of the Spiritual Athenaeum in London, where she showcased her striking art to a wide audience. Building on this success, four years later Houghton staged a large-scale solo show at the new British Gallery on Old Bond Street. A lengthy exhibition catalogue outlined some of the meanings behind Houghton’s art, expressing “a speech transcending mortal language.” Audiences were equally dazzled and perplexed – a critic from The Era newspaper called it “the most astonishing exhibition in London,” while another from The Daily News likened her art to “tangled threads of coloured wool.”

Much like the later Scandinavian spiritual artist Hilma af Klint, Houghton socialised in a somewhat marginalised pool of like-minded, predominantly female spiritualists, in whom she found a supportive and encouraging creative community. This meant her art was largely dismissed by wider, male oriented art audiences in her day, and the generations that followed. It is only recently that Houghton has begun to receive the widespread recognition she truly deserves. However eccentric or unbelievable the messages behind her art might be, there’s no denying her extraordinary gift for creating imagery that pulls the audience in close, and asks deep, penetrating questions about the ways we find spiritual and emotional meaning in the world.

5 Comments

Enita Torres

In addition to the wonderful linens, this is one of my favorite things about fabrics-store.com: blending art and history with the creativity of fabrics. Many thanks.

Linda Hobden

Another wonderful article and a discovery for me … thank you, so enjoy your posts.

Cassandra Tondro

Wow! What amazing art. I hadn’t heard of her before, and I so appreciate you bringing her work to my attention. Thank you!

Nancy Stockman

agreed!

Vicki Lang

What lovely paintings and such bold colors. Rainbow has always been my favorite color and it seems it was Georgiana’s also. Thank you for bringing her to light in your article.