The Bauhaus: A Unity of the Arts

The Bauhaus remains one of the most iconic and influential art and design schools of the modern world, and its legacy lives on today. Founded in Weimar by the great German architect Walter Gropius, the school’s aims were visionary and utopian. Gropius’s goal was no less than an entire unity of the arts, bringing all areas of art, design, craft and technology into a singular whole. He hoped to achieve this vision by placing greater emphasis than ever on skill and high-quality craftsmanship, writing, “architects, sculptors, painters – we must all turn to the crafts … The artist is an exalted artisan.” Although the Bauhaus eventually fell victim to Germany’s right-wing politics, many former students and staff emigrated to the United States, where their ideas spread far and wide.

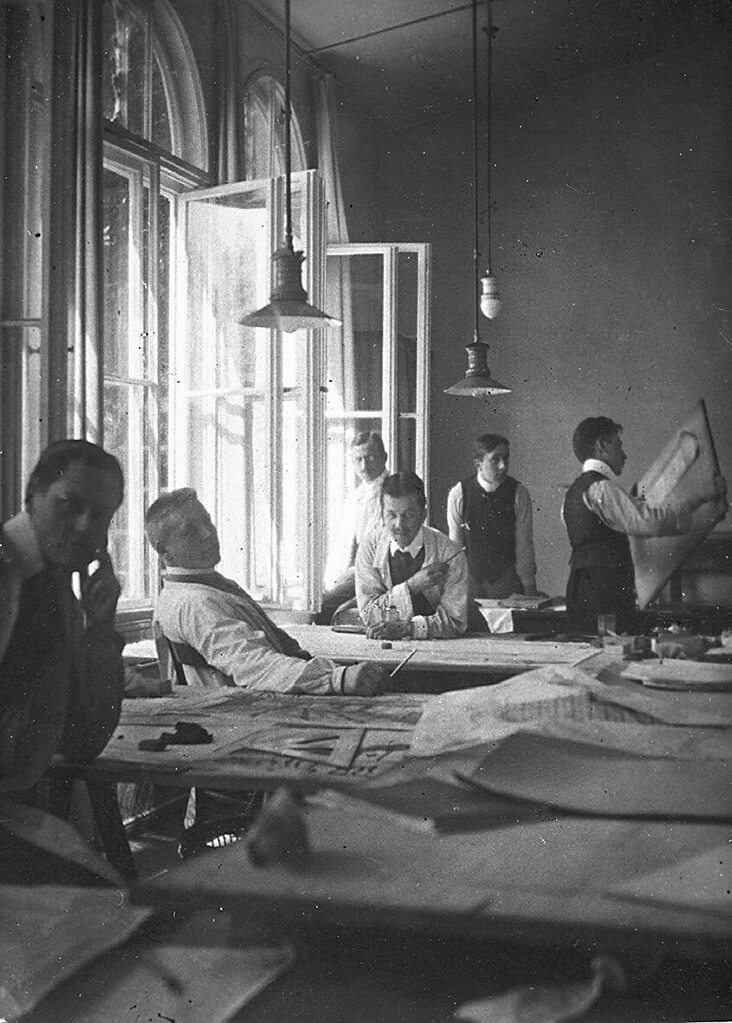

Gropius opened the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919. Having already established a career as an architect, building design was a fundamental principle in the school’s ethos. Gropius even named the school from the German words ‘bau’ (to build) and ‘haus’ (house). The name reflected the school’s underlying principles; Gropius put the notion of the house at the centre of his educational vision, likening his school to a home where all arts could co-exist in harmony with one another. Craft, or making, was at the centre of Gropius’s vision, and he compared the Bauhaus to a guild, where students would be trained to the highest standards in making.

Wassily Kandinsky, Scharf-Ruhig, 1927, made during the peak of the artist’s involvement with the Bauhaus

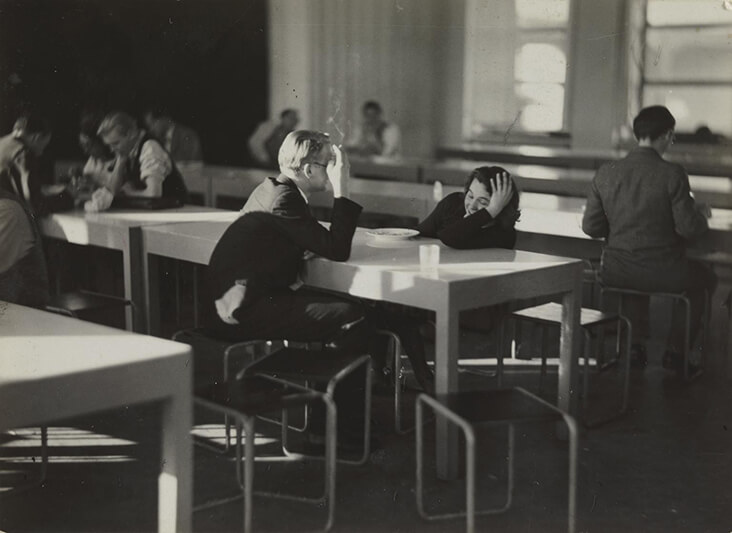

While the traditional 19th century art academies taught students precise figure drawing skills, the Bauhaus led its students in an entirely different direction. In their first year of study, students learned about colour theory, taught by Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky or Josef Albers, among others. They then moved on to train in specialised, lab-like workshops, which taught a whole range of skills, including metalwork, cabinetmaking, weaving, pottery, theatre design, typography and wall painting – each discipline was taught by a master in their trade. Artists were also encouraged to explore bold, simplified styles of geometric abstraction with solid shapes and futuristic curving lines instead of realism or detail, and to play with materials in novel new ways. It was these methods in particular that came to define the distinctive Bauhaus style.

For all its radicalism, however, the Bauhaus was still a symbol of its times, and the school generally took a less progressive and inclusive attitude towards women, who were largely excluded from sculpture and painting departments, and expected to enter the weaving studio. That didn’t stop many of them becoming outstanding artists with extraordinary skills, such as the textile artist Anni Albers. And all students were offered a range of opportunities, including public commissions, and collaborations with other art and design schools. Many of the female students also earned an additional revenue for the Bauhaus through the sale of their fabrics and textiles.

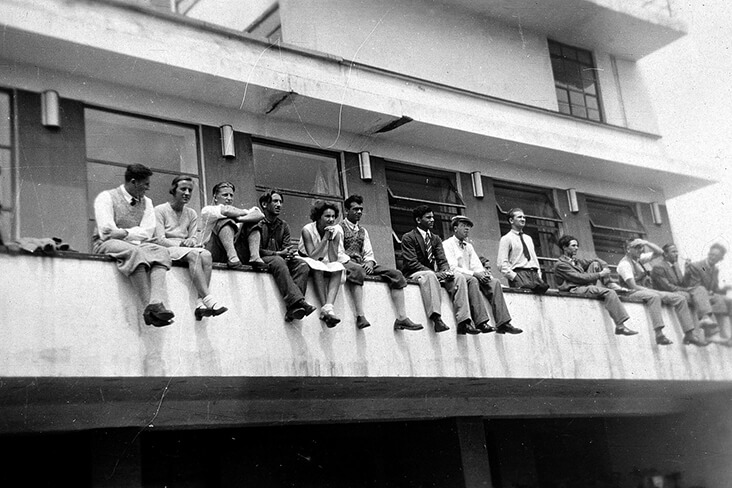

In 1925, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau, where Gropius had designed a new premises. The building he created was the ultimate showpiece for the Bauhaus style, featuring a geometric, modernist style throughout the exterior and interior. When Gropius stepped down from the leadership role at the Bauhaus in 1928, the institution had already begun to change, with a greater emphasis on taking art into industry, and the production of useful objects that could play a role in the lives of ordinary people. His successor was the architect Hannes Meyer, later followed by the architect Mies van der Rohe in 1930. By the early 1930s, the Bauhaus’s emphasis on intellectual freedom and experimentation was under threat from Germany’s rising Nazi party, and sadly, the school was forced to close in 1933.

This was far from the end for the visionaries who had pioneered the Bauhaus. Many emigrated to the United States, bringing with them their most radical ideas. Josef and Anni Albers became founding teachers at the innovative Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and Josef later went on to teach at Yale University. Meanwhile, both Breuer and Gropius secured teaching posts at Harvard. Moholy-Nagy founded the eccentric New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937, which was later absorbed into the Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies van der Rohe was both a teacher and site designer. Being allowed to continue their ground-breaking work around modernist design aesthetics in the United States meant the legacy of the Bauhaus lived on, shaping the nature of design across Europe and the US. The school’s radical teaching style had a particularly profound impact on the way design was taught for many generations after, and many of its lessons around simplicity, geometry and craftsmanship live on in many art and industry schools around the world.

3 Comments

ana Bonifacio

Thank you! I really enjoy it!

Stephanie Hammer

I really enjoyed this posting. I studied the history of architecture at university, and was fortunate to have excellent professors in this subject. It was a pleasure to revisit this topic. Thank you.

Jeannette Kossuth

I learn so much for Ms. Lesso’s articles, and I appreciate the wide ranging interest in textiles reflected in her articles. I often find her articles a catalyst for exploring new ideas related to sewing and the fiber arts. Bravo, Rosie Lesso! I hope you continue to inspire us for years to come !