FS Colour Series: POPPY SEED Inspired by Roger Hilton’s Grey Days

POPPY SEED Linen’s cold, steel grey often made its way into British painter Roger Hilton’s abstract art, suggesting the dark, muffling clouds of an oncoming storm. Hilton was a leading figure in British postwar abstraction, and a member of the St Ives group alongside Ben Nicholson, Peter Lanyon and Wilhelmina Barnes Graham. Like them, his art was an intuitive reflection of his outer and inner worlds, simultaneously capturing the metallic shades of the British weather, and his emotional responses to them. He said, “Painting is feeling. There are situations, states of mind, moods etc., which call for some artistic expression; because one knows that only some form of art is capable of going beyond them to give an intuitive contact with a superior set of truths.”

Hilton was born in 1911, and raised in Northwood, Middlesex in England. His mother was a painter who had trained at the Slade School of Art in London, and Hilton followed her path, entering the same school in the late 1920s. As a young graduate Hilton travelled widely – he spent several years living in Paris, and visited Amsterdam, places where avant-garde styles of geometric abstraction were taking hold. Hilton later moved back to England, but he continued to travel around, taking up various different teaching jobs along the way.

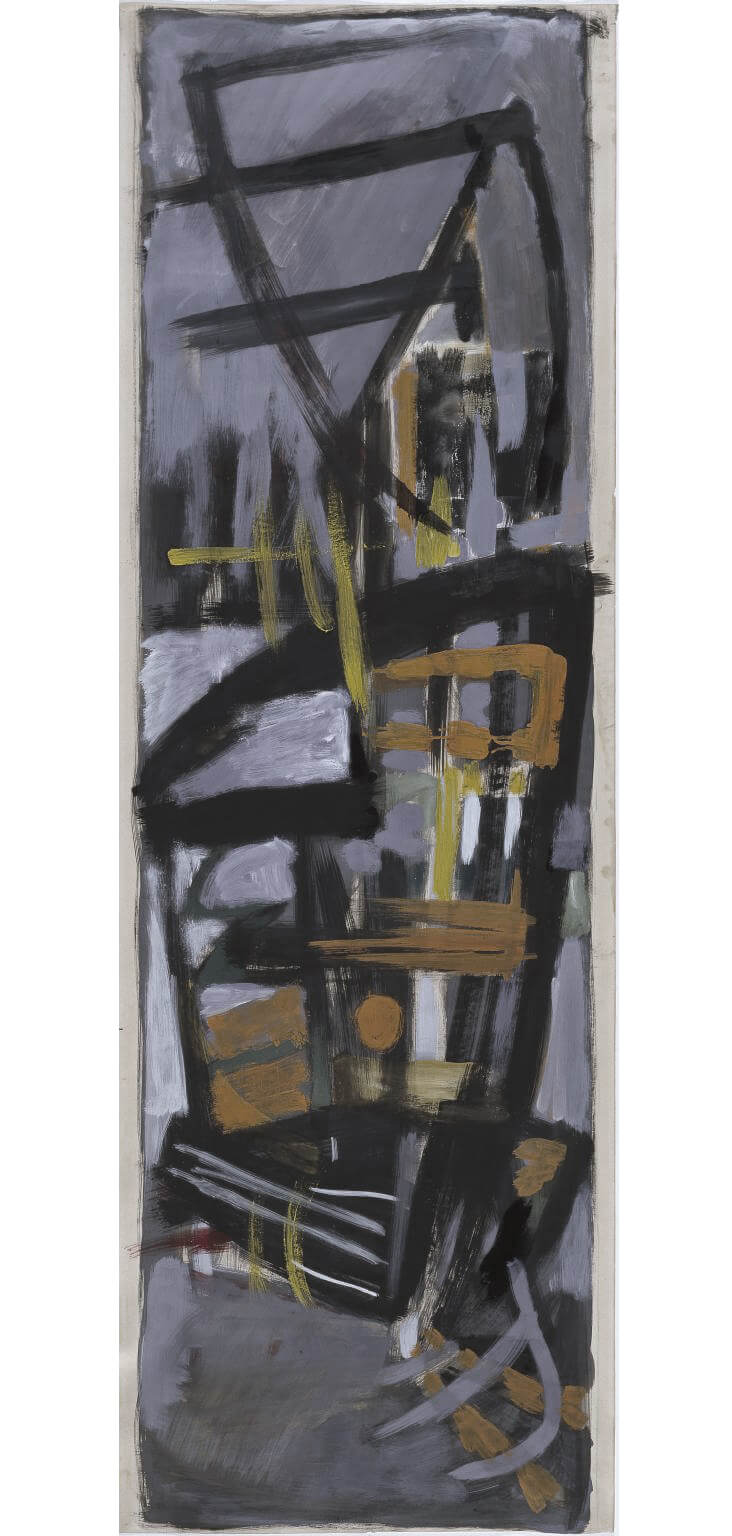

It wasn’t until the 1950s that Hilton fully embraced a completely abstract style of painting in his own art. Composition in Orange, Black and Grey, 1951–2 is one of the first abstract artworks Hilton ever made. Painted with striking calligraphic lines onto a deep grey backdrop, this painting reveals the influence of the French Informel style on Hilton’s early art. The colour scheme of metallic greys, coupled with bold black, and small slashes of brightness set the tone for Hilton’s art to come.

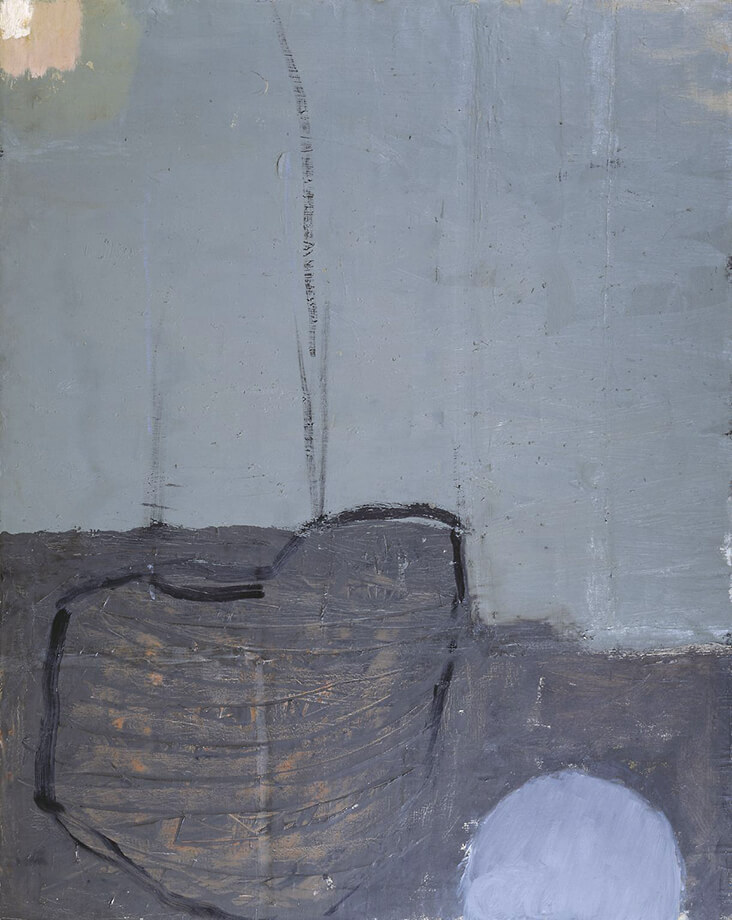

June – September 1953, is another early example of Hilton’s burgeoning new abstraction, which this time demonstrates Hilton’s admiration for the Dutch De Stijl simplicity of Piet Mondrian. But in contrast with Mondrian’s machine-like precision, Hilton retains a crude, painterly language, playing with how to create depth and movement by applying varying densities and textures of paint. Muted shades of grey act like foundational building blocks, with the solid, weighted permanence of rocks, while carefully arranged patches of brown, black, red and green are scattered around them.

In 1956 Hilton began making regular visits to St Ives, and by the 1960s he had settled there permanently, integrating himself with the lively art community. The rough and ready Grey Day by the Sea, February 1960, seems to capture the rugged, unspoilt wonder of a freezing cold winter’s day on the Cornish coastline, although Hilton deliberately resisted easy categorization for this, and other similar artworks, “The picture has no more or less to do with the sea or grey days than any other picture in my exhibition though naturally, I hope a little of sea and land and grey days and bright days comes into all of them.”

By the early 1960s Hilton had earned a widespread, international reputation as one of the UK’s leading abstract artists. But he shocked everyone with a departure into semi-figurative imagery in the early 1960s. Figure, February, 1962 demonstrates this stylistic shift, and reveals how the artist was toying with the boundaries between figuration and abstraction, much like the American Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning, and the British sculptor Henry Moore. Hilton has painted this dimly lit interior scene with his trademark muted shades of beige, brown, cream and grey, along with the smallest slashes of electric blue. Dark grey is less dominant this time, but it slices into the warmth of the brown around it with the cold, metallic sharpness of a knife, like freezing winter air making its way inside the room and onto the reclining model’s skin.

Leave a comment