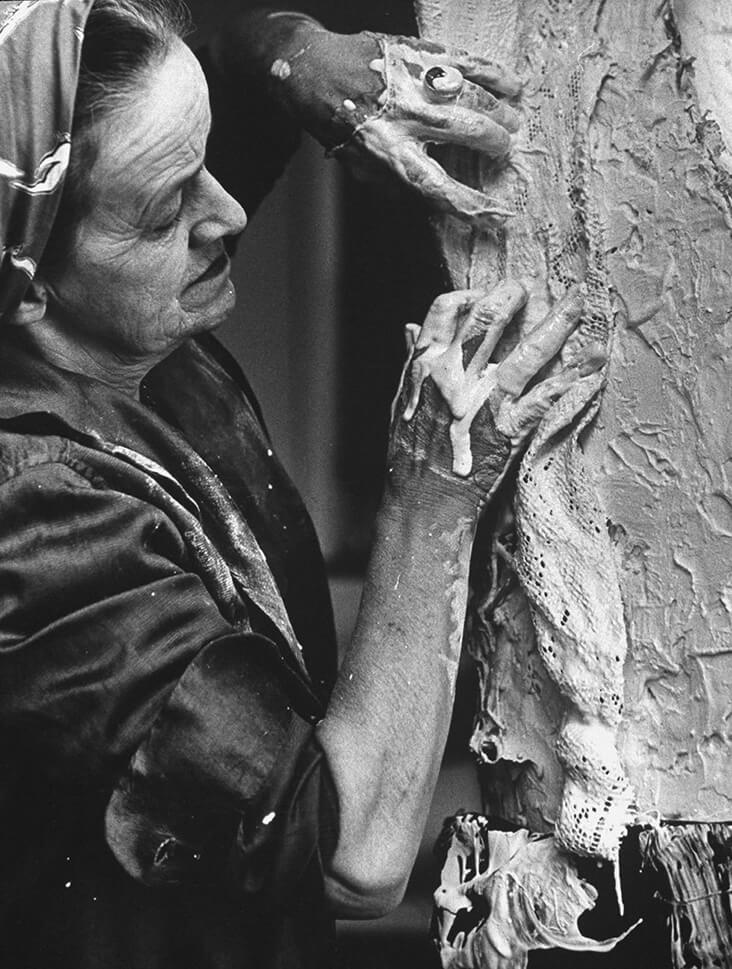

Making It Work: Barbara Hepworth on Motherhood

Motherhood is a recurring theme in the art of British sculptor Barbara Hepworth, an intimate subject so close to her heart she would return to it over and over again. Mother to four children, she juggled raising them almost singlehandedly, while continuing to create some of the most important and enduring sculptures of the 20th century. From afar, some say she made it look like an effortless feat, but in reality, she faced many struggles and sometimes had to make painfully difficult decisions along the way. In spite of this, interviews and private letters reveal how much she truly cherished her children, and how the experience of being a mother profoundly shaped her creative life. “…being a mother enriches an artist’s life,” she once told a friend.

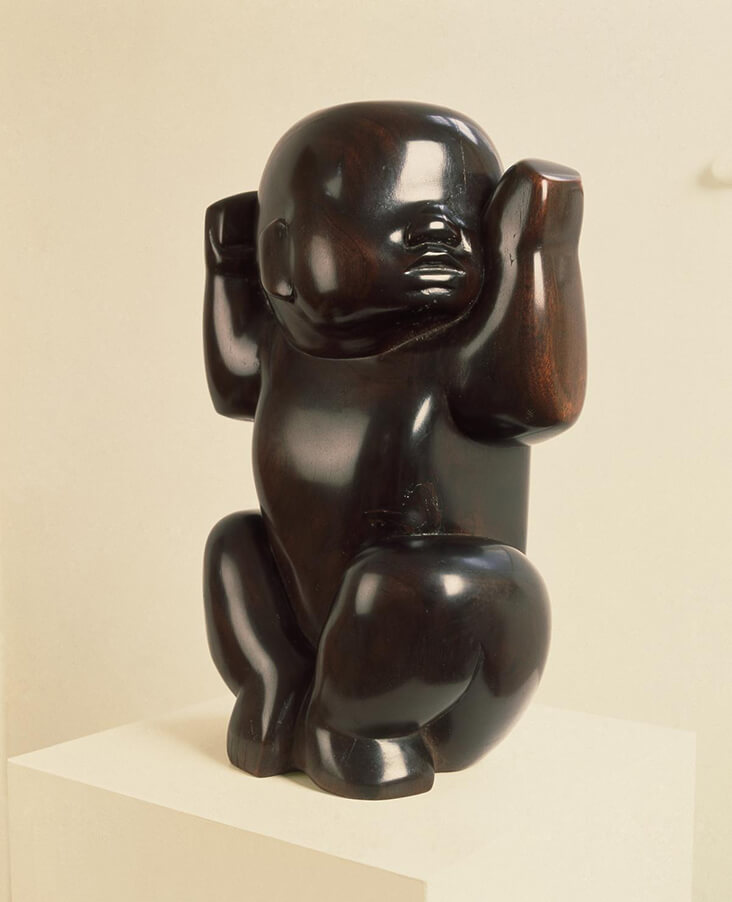

Hepworth was a pioneer from an early age, earning a place to study at London’s prestigious Royal College of Art in 1921, a time when women were seldom afforded the same educational freedoms as men. As a young graduate from 1924 onwards she hit the ground running, immersing herself in London’s thriving art scene and steadily making a name for herself as a leading avant-garde artist. The theme of motherhood first appeared in her art around this time. In 1929 she gave birth to her son, Paul, with her first husband, the sculptor John Skeaping. Not long after his birth, Hepworth created the sculpture Infant, 1929, a poignant response to the profound intimacy she experienced after becoming a mother.

By 1931 Hepworth had divorced Skeaping and begun a new life with the painter Ben Nicholson. Mother to a young child by now, the bond she had with her son continued to play out in Hepworth’s art, which often combined dual forms, as seen in the deeply personal Two Heads, 1932. In 1934, Hepworth fell pregnant with triplets. During her pregnancy, she made some of the most important sculptures of her early career, which reflected on the nature of human intimacy while gradually moving closer to complete abstraction. Mother and Child, 1934, is one of her best-known and celebrated sculptures, in which two human forms are carved from the same block as if intimately bonded together, yet their bodies are separate, each with their own individual agency. Hepworth’s friend, the art critic Adrian Stokes wrote, “This is the child which the mother owns with all her weight, a child that is of the block yet separate, beyond her womb yet of her being.”

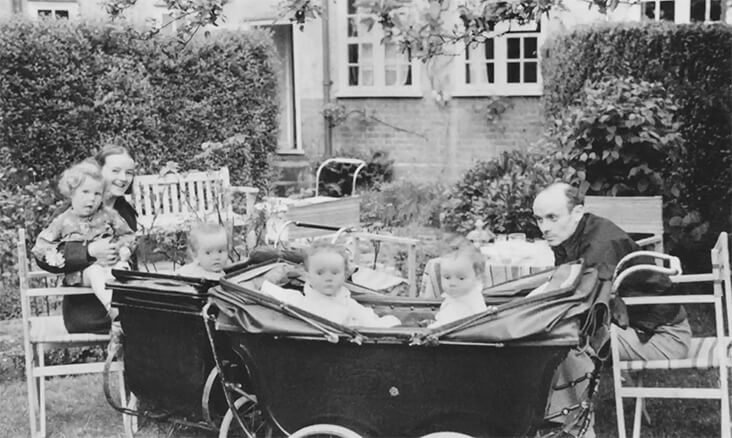

When Hepworth gave birth to her three triplets, Rachel, Sara and Simon, she was undoubtedly overwhelmed. Nicolson had run off somewhere (they had an open marriage), while she was left completely alone with three fragile, sickly infants in a tiny, cramped flat in Hampstead Heath. Friends reported that she would cry for days on end, and was unable to leave the house for weeks as the cold weather was too harsh for her tiny babies. When they were four months old, Hepworth put her triplets into nursery, a decision for which she received harsh criticism at a time when women were expected to be full-time carers for their babies. But it was the right move for her, allowing her to gain freedom to make art again. She once told a friend: “I’m not fit to live with unless I can do some work – even an hour a day keeps me civilised.”

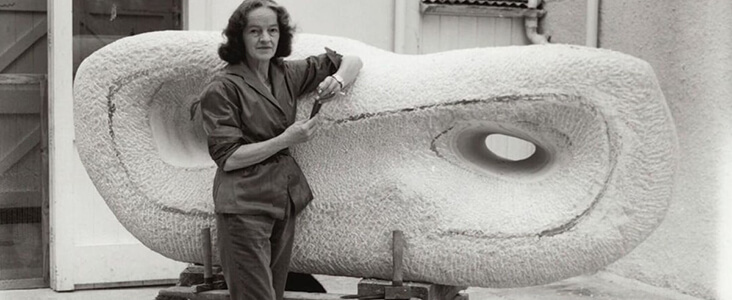

Art historian Caroline Maclean observed this back and forth struggle the artist wrestled with between her career and her children, “The thought of not having them with her made her deeply unhappy, but the thought of not working also made her unhappy.” When they were one, Hepworth took her triplets out of nursery and began caring for them at home as she could manage. She established a studio space filled with music, toys and poetry, a creative space they could all enjoy together. “My studio was a jumble of children, rocks, sculptures, trees, importunate flowers and washing,” she recalled.

In 1939, just before the outbreak of war, Hepworth, Nicholson and their young children all relocated to a small house in Cornwall. Living conditions were cramped and overcrowded, and Hepworth found it almost impossible to keep making art. She worked in the darkness at night when she could, but it was not until 1943 that she found the time and mental space to make major work again. Moving to a bigger house with a large garden in 1943 helped make it possible for Hepworth to find creative freedom. The art she made from this point onwards continued to reflect on her role as a mother. References to triplets appeared in her standing trios, while even her most abstract work had a bodily feel, suggesting the close physical intimacy of being a mother, sometimes with one form wrapped over another like a protective shield.

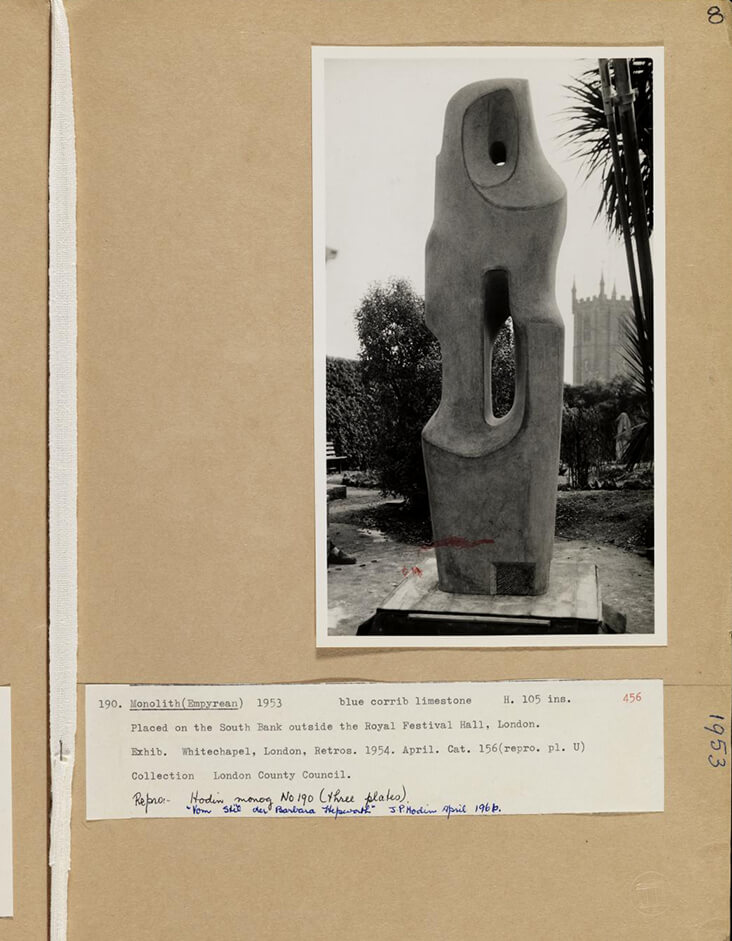

Monolith (Empyrean), Limestone, 1953. A memorial to Hepworth’s son Paul Skeaping and his navigator, who were killed on active service with the RAF in 1953

When her daughter became gravely ill during the war, art was one way of coping, as Hepworth noted: “I thought the only thing I can do to help this awful situation, because we never knew if it would worsen, is to make some beautiful object. Something as clean as I can make it as a kind of present for her.” In 1953, when Hepworth’s first son Paul was tragically killed while serving in the Royal Air Force in Thailand aged just 20 years old, Hepworth again found solace through art, making the emotionally raw, Biblical-style Madonna and Child, 1954 in his memory.

All this proves that motherhood was woven into who Hepworth was, and it became the heart, body and soul of her art. Looking back in her later years, she observed, “I loved the family and everything to do with them. I loved the environment and the cooking…I enjoyed it you see; it was part of me.”

4 Comments

Jonathan Hill

My parents were working and living in the Carbis Bay Hote, St Ivel in the mid 60’s.

Dad was a chef and mum a waitress, we lived in a long gone cottage behind the hotel. Barbara came in most afternoons for tea. She would borrow new born me and take me for strolls around the car park or bounce me on her knee whilst chatting with mum and dad. Dad says she often spokle of her loss during these moments.

Here’s the kicker, I am now a high school sculpture teacher!!!

Beth Pritchett

I am a mother of four, birthed within six years of each other, and I was trained as a classical trombonist. Her struggle resonates with me. I have found artistic outlets in sewing, even in figuring out how to manage my small but overflowing household in a tasteful manner. Music is difficult for me to approach, but sewing feels like a service as well as an outlet, whereas the selfish isolated musician comes out when I even listen to what I used to love. I have it up for many reasons, and try to reconnect with some post of my artistic sense whenever I can. An hour at my machine or just ironing linen that will become a simple but carressible garment is therapy that keeps me calm, human, and more willing to focus on my children during the other endless hours of my days.

Milica Virag

Just loved reading about this artist Barbara Hepworth and admire her sculptures. So much of emotion and strength is shown as she worked and lived her life as an artist and mother, I feel it, well written, well presented. Thank you.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you so much! That’s so nice to hear. I also think she is a real inspiration…