Asafo Flags: An Introduction

Asafo flag featuring a five headed dragon, cotton with hand sewn appliqued figures and embroidered details, attributed to the Fante people, Ghana, Christie’s

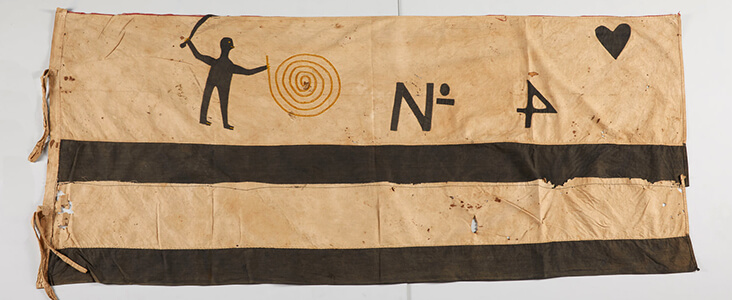

Vivid, striking and bold, Asafo flags are part of a three to four-hundred-year-old history, and they are still being made today. Originating from 17th century Ghana, hand-made Asafo flags are filled with powerful symbols, stories and metaphors. Much like quilts, these flags have often been passed through families from one generation to the next, holding secret stories about their ancestral past. In recent years, traditional Asafo flags have also become much prized collector’s items for a rising number of enthusiasts, who are attracted to the flags as much for their striking designs as the incredible history hidden within them. Newer flags are just as vivid and striking as those of the past, and they have much to tell us about Ghana, past and present.

The history of Asafo flags can be traced back to the Fante people of late 17th century Ghana who lived in the Southern Coast fishing villages of Anomabu, Saltpond, Mankessim, and Elmina, and the town of Cape Coast. They were enthusiastic buyers of imported cloth from European markets, and were highly skilled makers. During the 17th century, various different military companies known as ‘Asafo’, or ‘War People’ (‘sa’ meaning war and ‘fo’ meaning people) were established by citizens of Fante who had formed allegiances with British and European settlers.

Traditionally made by men, Asafo flags, known as Frankaa, held great significance for these military groups, allowing areas to assert their independence from one another. Flags also became a ceremonial tool to be used in public celebrations and even dance rituals, a tradition that remains alive to this day. In the 17th century it is thought the flags were painted and drawn onto raffia cloth, but they later evolved into appliqued masterpieces made with trade cloth from a variety of sources. The allegiance groups had with Europe, and particularly Britain is shown by the inclusion of the union jack in the corner of many designs.

In the main body of the flag, a variety of motifs were included in simple, elegant designs, particularly those which demonstrated the status and power of the group. Proverbs and allegories were hugely popular, especially those related to nature and animals – Ghanaians believed creatures were more powerful than human beings. The crocodile, for example, represented strength and authority – one flag illustrates the proverb of The Fish and the Crocodile, which describes how “fish grow fat for the benefit of the crocodile who rules the river”. In another, illustrating the proverb of The Big Waterbird, who “swallows fish from a different angle”, the flag suggests how this group can achieve things others might find too hard.

When British colonial rule took over, the military associations with these flags ended, but the symbolic and ritualistic role of the flags remained, and today, makers produce flags to celebrate their allegiance to Fante village life, and to Ghana. Flags are flown during festivals and funerals, and paraded around the village. Recent flags have often replaced the union jack with the Ghanaian flag in one corner, and they lean towards contemporary stories of political and metaphorical ideology rather than ancient proverbs. It is worth noting that in the past decade the makers of flags are gradually being recognised as individual makers, rather than anonymous representatives of their entire group.

The significance of Asafo flags is well known within Ghana, but in recent years various collectors have raised their profile to a wider, international audience. These include British curator Barbara Eyeson, who has been gathering her own collection of flags for over 10 years, after identifying the roots of her family’s history in Ghana, and has founded the company Asafo Flags to celebrate their rich legacy. She is fascinated by the range and diversity of Asafo flags, and observes how, “They all tell a story.” British historian Gus Casely-Hayford has also traced his family history back to Ghana, and really saw how significant the flags were, and still are, after going to see one of his father’s old flags. He remembers, “It was just a fraying, fractured piece of cloth that had obviously seen better days but you got a sense of how much these things mean to people. How what seemed like a ragged piece of cloth could actually represent a life, a person’s biography.”

6 Comments

Stephanie Hammer

Thank you for this wonderful article about this dynamic textile form. I always learn from your postings, and look forward to the next one. Thanks!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you!

Alisha Cooke

This is really fascinating Rosie. Thank you for sharing this history. If the early flags were thought to have used raffia cloth, and then cloth imported from European markets, do we think they used linen or a variety of linen, cotton and even possibly silk?

Rosie Lesso

Hi Alisha, thanks for the comment! Its a very good question… As far as I can see the majority of flags were made with cotton, but it is very possible they might have incorporated other fabrics like linen and silk too given they were working with trade cloths from European markets…

Vicki Lang

What wonderful needle work. The flags have such unusual depictions and so colorful. thank you for the great history.

Rosie Lesso

Thanks so much!