Ancient Meets Modern: Diaghilev and De Chirico

Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico and ballet director Sergei Diaghilev only worked together on one Ballets Russes production, but their union would prove momentous and life-changing for both. Their collaboration was significant for Diaghilev because it was the last production he would produce before his death later that same year. It was also important for the respected Italian painter De Chirico, launching him a new career path in theatre design. De Chirico’s designs revolutionized a new approach to ballet, merging the classicism of ancient Italy with the avant-garde languages of Parisian modernism.

Giorgio De Chirico Costume design for a male dancer in the Ballets Russes production of Le Bal, 1929, V&A Museum, London

Diaghilev approached De Chirico with a ballet commission in 1929. It is easy to see why the strange, dramatically lit world of De Chirico’s art would have piqued Diaghilev’s interest, with its emphasis on theatricality, long shadows and carefully placed props. Diaghilev was particularly fascinated by the depth and breadth of Italian historiy, and he saw how the tall columns and ancient statues of De Chirico’s paintings might translate into awe-inspiring and atmospheric results on the theatrical stage.

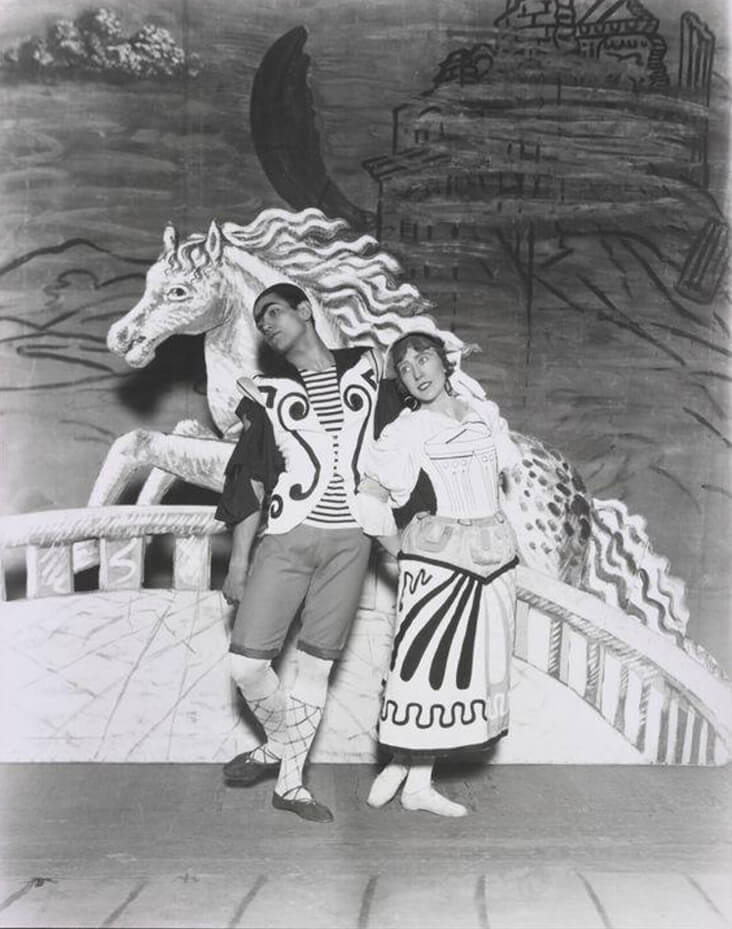

A male and a female dancer performing in Giorgio De Chirico Ballets Russes production of Le Bal, 1929, V&A Museum, London

The production that Diaghilev had in mind for De Chirico was Le Bal, (The Ball), a two-scene ballet written by Russian-French librettist and writer Boris Kochno, based around the theme of a masked ball, with music by Vittorio Rieti and choreography by George Balanchine. Central to the ballet’s storyline was the concept of duplicity and deception, and Diaghilev saw De Chirico as the ideal visionary to create a dizzying, dream-like world of smoke and mirrors.

A male and a female dancer performing in Giorgio De Chirico Ballets Russes production of Le Bal, 1929, V&A Museum, London

Within his paintings, De Chirico was fascinated with the ghostly quality of ruined statues, particularly when placed in an unusual context, where they can seem to come to life, like, as he described, “a person glimpsed in a room that we thought was empty.” This eerie and uncanny quality was the starting point for De Chirico’s designs with Diaghilev. We see this odd, dislocated quality in De Chirico’s scenery, which featured broken and discarded fragments of classical architecture, distorted angles and enlarged areas of cornicing, immediately creating a disorientating and unsettling arena for the ballet to play out.

Giorgio De Chirico Costume designs in the Ballets Russes production of Le Bal, 1929, V&A Museum, London

But most radical were De Chirico’s costume designs, which experimented with dancers as an extension of the background, who seem to merge out of its strange angled distortions like spirits from another world. He achieved this effect by designing costumes featuring mismatched architectural fragments, including printed panels of red brick pattern, classical white pillars and columns, and the curling motifs of classical orders and arabesque swirls that accentuated the natural curves of the body. To further enhance the ghostly, ossified quality of his dancers, De Chirico gave them white stuccoed wigs and beards. Two of his dancers were dressed in skin-tight white leotards adorned with loosely drawn fig leaves, to make them resemble classical statues. Even though they barely moved throughout the entire performance, De Chirico described them as “endowed with a magic power from an unreal world.”

Le Bal was unveiled by the Ballets Russes at the Theatre de Monte Carlo in May 1929, where audiences were immediately captivated by De Chirico’s surreal architectural vision. The production then successfully toured Paris, Germany and London, closing with a final performance at the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden. Perhaps it is fitting that Diaghilev’s final ballet production was Italian in spirit, for it was in Venice just one month later that he died, leaving behind a vast and extensive legacy. The success of Le Bal succeeded Diaghilev, with a revival in 1935 by Diaghilev’s successor Colonel de Basil in Chicago in 1935. De Chirico, meanwhile, went on to further his love of theatre with designs for the De Basil’s Ballets Russes productions of Pulcinella in 1931 and Protee in 1938, as well as working with the Paris Opera and several Italian ballet companies. The magical aura of the stage also made its way into De Chirico’s late paintings, which ripple with the same haunting quality of fragmentation as his wayward designs for the theatre.

6 Comments

Diane Lockwood

Miss Lesso, like Danuta, I enjoy your posts and the other contributor’s posts. I would have never thought fine arts and entertainment would be subjects explored on a fabric website. It has exposed me to subjects I didn’t know I was interested in. Thank you.

Rosie Lesso

That’s great, thanks so much for taking the time to post! I agree Masha does an amazing job as editor overseeing so many different topics…

Danuta Snyder

I’ve meant to write before. I so enjoy these articles. To contemplate shades of colour expressed by artists feels luxurious. And the series related to ballet and set designs and costumes are wonderful! Thank you!!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you! The Diaghilev series was Masha’s brilliant idea and it has been a fascinating subject to write about…

Carol Etchemendy

As a weaver, spinner, dyer, and sewer, as well as having a degree in Art, I really appreciate your posts. They give me information I didn’t know before and are so inspiring. Many, many thanks.

Rosie Lesso

Thanks so much – that’s so nice to hear!