Titans of Architecture: Aline and Eero Saarinen

“The more one digs, the more one finds the solidest [foundation] for you and I to build a life together.” Eero Saarinen

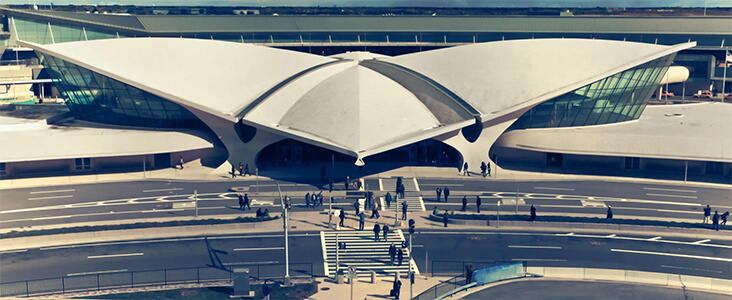

Aline and Eero Saarinen are considered titans of the architectural world, each having made vital, long-lasting contributions to the landscape of American modernism. She was the esteemed writer and broadcaster who made architecture accessible and fun, while he was the architect whose streamlined visions led to the masterful Gateway Arch of St Louis and the TWA airline terminal in New York. Together they shared a driving, unrelenting ambition to make a difference in the world through the visionary realm of architecture. Love letters between the two reveal how they also shared an ardent, passionate love affair, but it was not without its difficulties and inequalities as their relationship gradually unfolded.

Aline and Eero Saarinen enjoy a boating holiday together, 1953, image courtesy of the Archives of American Art.

By the time Eero Saarinen and Aline Louchheim met in 1953 in Michigan, both had established careers and families. Aline was an accomplished art critic and editor for the New York Times, but also recently divorced with two teenage children. Eero, on the other hand, had established his own architectural firm in 1948, and was still married, albeit unhappily, with two young children. Aline was hired to write an expose on Eero for the New York Times, to promote his recent completion of the General Motors Technical Centre, an impressive collective of 25 streamlined buildings which critics hailed an “industrial Versailles.”

Aline adored Eero’s master plan, describing it as a “a twentieth century monument”, and the pair spent two intensive days together discussing the concepts that drove his vision. There was an immediate chemistry between them that neither could ignore and after parting company, the pair went on to share an intimate correspondence that would keep the flames of passion alive. Alina wrote in a letter to Eero, “I looked at you very intently and thought how much I did want to see you again.”

Within just a year Eero had left his wife, and he and Aline were married. Aline’s role as a writer was undoubtedly compromised by her marriage – she believed she could no longer write unbiased exposes on architecture married to such a prominent architect, so she resigned her role with the New York Times – instead, she became Head of Information Services at Eeero Saarinen & Associates. On Alina’s part, this shift might be seen as a submission of her own interests, but she took it upon herself to become Eero’s primary publicist. “Now I observe myself ardently promulgating the Eero-myth,” she wrote in a letter to a friend. Although some historical accounts gloss over the role of Alina in Eero’s career, she had insider contacts that proved hugely beneficial for the promotion of his ideas, even landing him a cover of Time magazine in 1956.

Aline and Eero Saarinen sitting on his famous “tulip” dining set in their home, with son Eames, image courtesy of the Manuscript Archives, Yale University Press.

Despite the compromises Alina made in their early years of marriage when their son, Eames Saarinen, was born the couple decided to share a study space in their home together and so they could offer each other encouragement and support on their individual ventures. While sharing a workspace, Alina completed her book The Proud Possessors: the lives, times, and tastes of some adventurous American art collectors, 1958, which became an international bestseller, while Eero produced some of his most celebrated feats of architectural engineering, including Hill College House at the University of Pennsylvania, which combined a red brick exterior with a spacious, light-filled atrium inside, and the stunning Ingalls Ice Rink at Yale University, designed to echo the curved shape of a hump-backed whale.

Eero’s sudden and unexpected death in 1961 of a brain tumour was a devastation. His career was just taking off, with some of his most adventurous projects still in construction – Alina was instrumental in bringing them to life, overseeing the realisation of the space-age TWA airline terminal in New York, the soaring, elemental Gateway Arch at St Louis, the Washington Dulles International Airport and two more buildings for Yale University. In the years that followed Alina edited the deeply personal biography Eeero Saarinen on His Work, 1968, which included personal writing, drawings, photographs and research, and used her extraordinary writing talent to keep her husband’s vital contribution to American modernist architecture alive.

From 1962 onwards Alina also carved out a new career as an arts broadcaster, presenting a wide array of erudite and entertaining arts programmes – such was her success throughout the 1960s that the magazine TV Guide posed the question, “Why is Aline Saarinen a Cultural Institution?” Alina’s endless generosity of spirit meant Eero’s legacy lives on today, while she, herself is credited with shaping the open and approachable nature of architectural criticism today.

2 Comments

Iphigenia Hatt

Thank you for this article, well written, clear and absolutely wonderful!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the kind words – they are a fascinating couple!