From Russia with Love: Diaghilev and Goncharova

Lausanne, 1915 Participants of Ballet Des Russe. From left to right standing: Myasin, Larionov, Bakst, sitting- Goncharova and Stravinsky

With sparkling Russian skylines and intricately embroidered peasant dresses, Natalia Goncharova’s ballet costumes are an ode to the wonder of her Russian heritage. Better known as the progressive Russian artist who scorched her own path with Rayonism and Neo-Primitivism in the early 20th century, Goncharova also made a significant and long-lasting contribution to the world of theatre, creating costumes and sets for the Ballets Russes from 1913 up until the 1950s. It was her fellow Russian, the great ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev who would first introduce her to the wonders of the stage, and he was immediately struck by the impact of her designs, declaring, “Goncharova’s designs are simply fabulous! They are exceedingly poetic.” Little did he know her relationship with ballet would come to outlive his own.

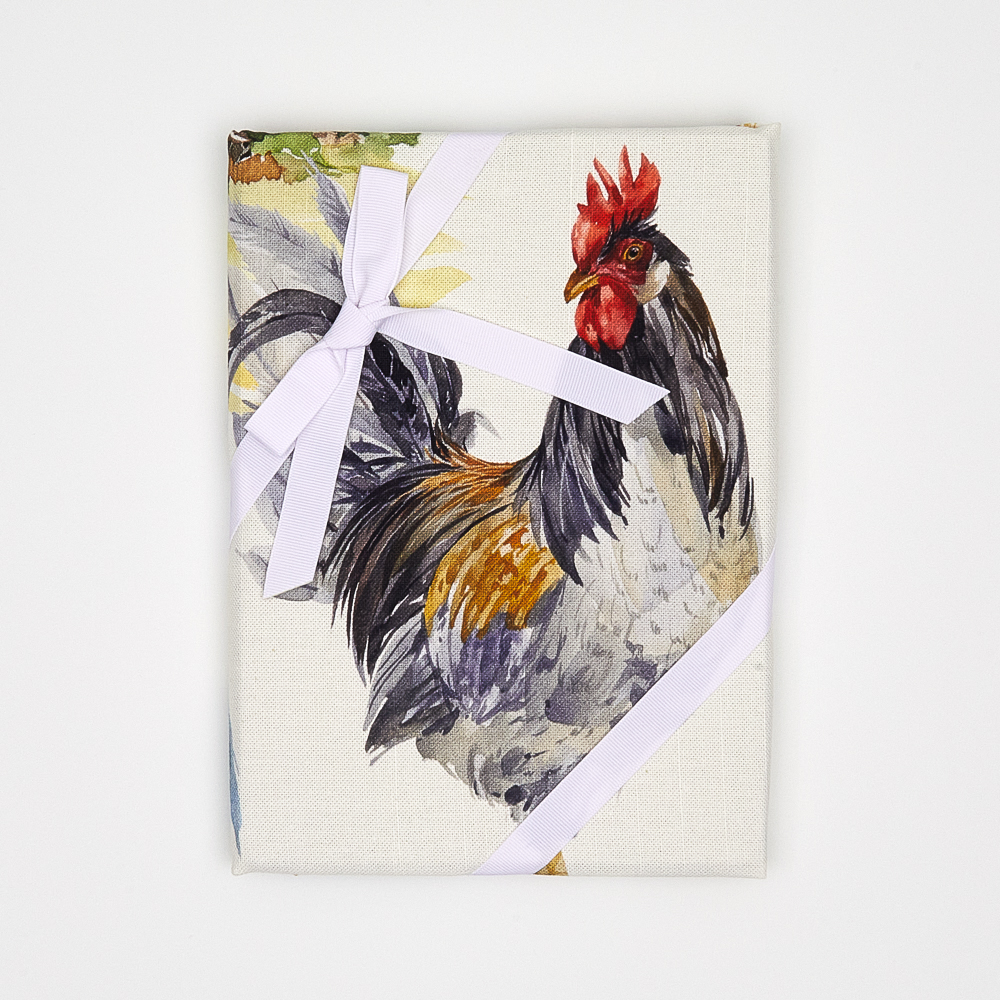

Although Goncharova had made her name as a radical artist in Moscow before meeting Diaghilev she had always enjoyed the theatricality of clothing and style, deliberately wearing men’s clothing or parading the streets of Russia topless, painted with bold streaks of colourful body art. It was this provocative and uninhibited self-expression that first attracted Diaghilev, who invited her to work on a production of Le Coq D’Or (The Golden Cockerel) in 1913, to be staged in Paris in 1914. The story was based on Aleksandr Pushkin’s 1835 poem The Tale of the Golden Cockerel, which itself had been adapted from a Russian fairytale, so it made sense to involve Goncharova, who had a deeply held affinity for her Russian upbringing.

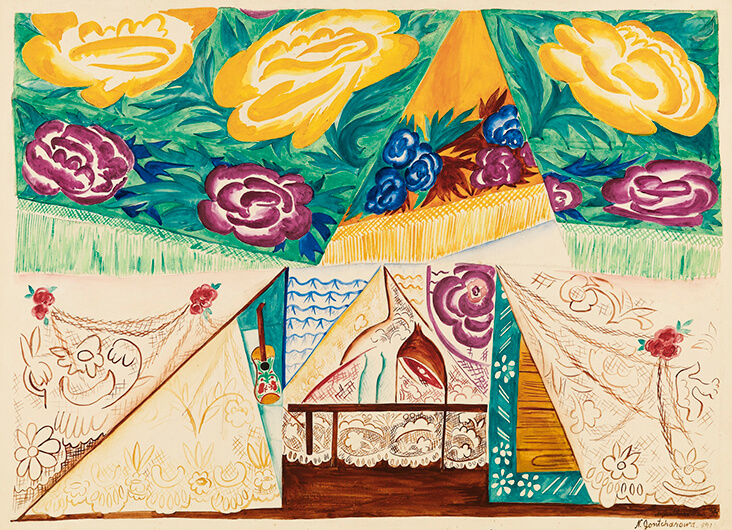

In her set and costume designs, Goncharova drew heavily from Russian history, bringing in the bold outlines and sparkling colours of Byzantine icon painting and the intricately embroidered floral patterns of peasant clothing, filled with searing flashes of golden red and yellow. She fused these historical references with the flattened forms and hard, angular edges of European modernity, dazzling audiences with the ingenuity of her designs. Prince Volkonsky observed at the time, “If the walls of the French Grand Opera had vocal organs, they would have gasped with surprise at what was being shown there.”

The success of the productions in Paris and London brought international fame for Goncharova, and Diaghilev was so impressed he invited her to become a lead designer for the Ballets Russes, marking a dramatic shift in her life and transforming her from what she called “an ordinary Moscow painter into a scenographer who travelled around the world.”

Natalia Goncharova’s costumes for the Ballets Russes production of Sadko, 1916, National Gallery of Australia

For the next 15 years, Goncharova worked side-by-side with Diaghilev on a series of hugely successful productions, moving widely throughout Europe with his troupe. Both shared a desire to bring the magic of Russia to European audiences, along with a fascination in the cutting-edge languages of avant-garde European art. They were both also fearless, charismatic leaders who dared to push into unchartered territory, making for one of the most successful collaborations of the 20th century.

Among the many ballet productions Goncharova worked on, Les Noces (The Wedding), 1923, was another roaring success, drawing once again from the beauty of peasant dresses and fabrics, merged with the faceted forms of Futurism to create a visual feast of colour, pattern and movement. It was the celebratory mood of the story that really fired up Goncharova’s imagination, as she explained, “At that time it was the festive, folk aspects of weddings that stood out for me, the colourful costumes and dances that connect weddings with holidays, enjoyment, abundance.” Inspiration came, in particular from a village wedding Goncharova attended as a child in rural Russia, filled with overcrowded happiness and excitement, with guests dressed in hand-woven clothing and vibrantly coloured headscarves.

In 1926 Diaghilev drafted in Goncharova to restyle his earlier production of The Firebird from 1911, which he now deemed too traditional. Rising to the challenge, Goncharova breathed new life into the famous folk tale with striking, immediately arresting motifs drawn from Russian iconography and folklore. Her backcloths and sets were particularly awe-inspiring, celebrating the atmospheric skylines of Russia with dazzling shades of red, blue and gold. After Diaghilev’s death in 1929, Goncharova continued to design sets and costumes for the Ballets Russes, along with a series of other companies and soloists until the late 1950s. Throughout all this tireless, prolific creativity she continued to bring her inimitable voice, one that merged Russian folklore with the radical breakthroughs of modernity.

Leave a comment