Masters of Illusion: Diaghilev and Picasso

The creative union between Pablo Picasso and Sergei Diaghilev is one of finest and most influential collaborations of the early 20th century, one that would forever alter the nature of ballet. Throughout his years as director of the prestigious and renowned Ballets Russes Diaghilev enlisted a wide pool of artists to work with, but his relationship with Picasso was one of the longest, most prolific and successful – in less than a decade they worked together on six separate ballet productions, each one venturing into unchartered territory. For Picasso, in particular, theatre was a gateway into a whole new arena of artistic exploration, infusing not only his creative practice but his entire sense of self.

In 1917 the Surrealist artist Jean Cocteau persuaded Picasso to travel to Rome to assist in the production of sets and costumes for a new, avant-garde ballet in the making, called Parade. From his isolated studio in war-torn Paris where Picasso was wrestling with synthetic Cubism and still recovering from grief at the loss of his lover, Eva Gouel, the prospect of travel and a new creative venture must have seemed an appealing escape. In Rome, Picasso immediately immersed himself in the world of theatre, soaking up the atmosphere with a constant stream of sketches and studies.

Diaghilev was impressed by Picasso’s dedication and the originality of his ideas, placing Picasso at the helm of the company’s creative vision. In Picasso’s eye, the theatre became a new arena to expand Cubism, a vast arena to take fragmented forms, disjointed angles and multiple perspective out from the flat plane and into real, moving space. His costume and set designs were harsh, angular and aggressive, playing with a deliberately confrontational visual language that seemed perfectly suited to Parade’s avant-garde mash up of music written by Erik Satie and choreography by Leonide Massine. Mainstream critics were appalled, while a small circle of avant-garde followers praised its ingenuity; the writer Guillaume Apollinaire referred to Parade as an “alliance between painting and the dance, between plastic and mimetic arts, that is the herald of a more comprehensive art to come.”

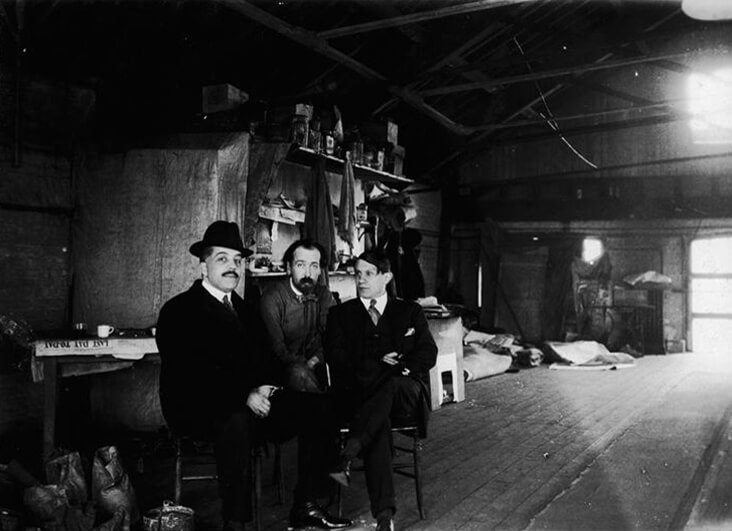

Pablo Picasso, (wearing a beret) and scene painters sitting on the front cloth for Léonide Massine’s ballet Parade, 1917. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

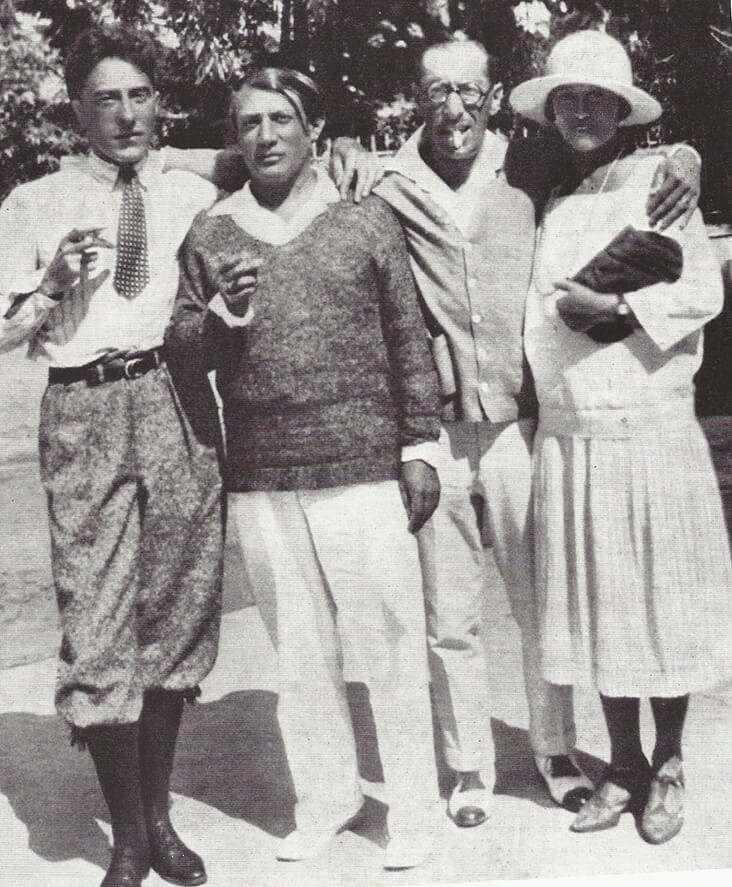

The ballet also fascinated Picasso on a personal level – he was entranced with the backstage dancers and glittering social scene that surrounded Diaghilev’s glamorous lifestyle. After avidly watching her from afar, Picasso fell in love with the Ballets Russes’ Ukrainian dancer Olga Khokhlova and they would go on to marry in 1918. She became a recurring feature in Picasso’s art, along with their son Paul, and the social life they shared amongst composers, choreographers and musicians only served to enhance Picasso’s deeper appreciation of the ballet.

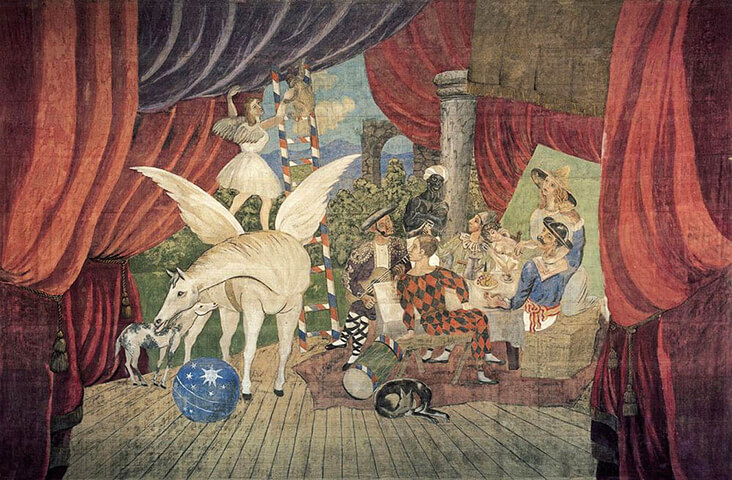

The next ballet production that Picasso and Diaghilev worked on together, Le Tricorne, 1919, was less directly confrontational than Parade, but equally as experimental. Telling a Spanish love story set in amongst the Andalusian mountains, it was a theme close to Picasso’s heart, allowing him to connect back to his native Spain. Backdrops were simple and rustic, painted with slabs of earthy colours to capture the heat of the Spanish countryside, while his costumes were flashes of celebration and joy, combining striking colours and patterns with streaks of black, recalling the art of Spanish masters Goya and Velasquez; these were ideas that would later feed back into his studio practice as he gradually returned to an increasingly figurative language.

Picasso was criticised by some for creating too much visual noise in Le Tricorne, but he was undeterred – he had already begun to see theatre as an extension of painting, as the contemporary art historian and Picasso scholar Douglas Cooper observed, “In Picasso’s mind, there exists a parallel between painting and the theatre … he has come to regard both as being different though comparable ways of creating an illusory world with images which nonetheless reflect, and so help us, the spectators, to recognise more about the world in which we live.”

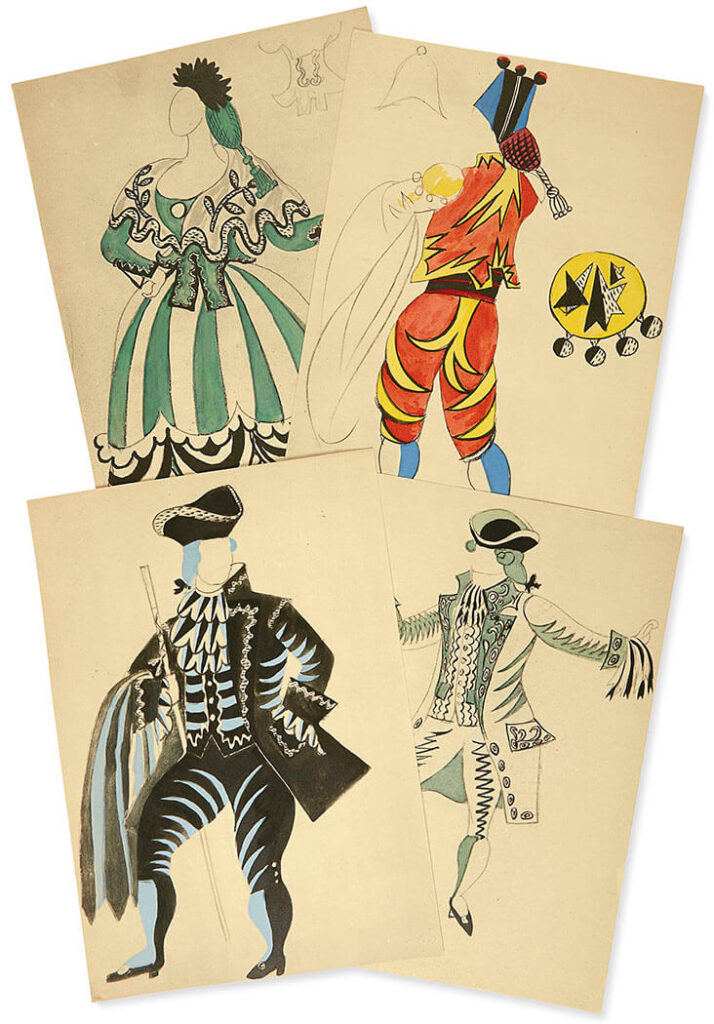

In the following years Picasso went on to create a full suite of sets, curtains and costumes for a further two productions, Pulcinella, 1920 and Quadro Flamenco, 1921, projects which allowed him to explore the stage as a flexible space where two and three-dimensional shapes could be enlivened through the movement of dance. Through his visionary designs these once traditional stories were entirely transformed into striking modernist masterpieces, reimagining the ballet as a site for clashing avant-garde styles, shapes and forms. Within his work for the ballet, Picasso gradually moved into an ordered, neoclassical style, one which would also spill out into his wider studio practice. The vast curtain he produced for Le Train Blue, 1924 and the décor for Mercure, 1924 reveal this shift in his practice with loose, draped clothing, linear flowing lines and restrained colour schemes.

Pablo Picasso’s Spanish style costume designs for the Ballets Russes production of Le Tricorne, 1919

Though Picasso’s association with the ballet would peter out after 1924, the experiences he had with Diaghilev would prove life-changing, pushing him towards ideas that might never have otherwise been realised. In particular, the epic scale of Picasso’s backdrops and theatrical curtains undoubtedly paved the way for the vastly sized Guernica, 1937, one of the most important works of his career. Many of the props, costumes and sets Picasso made still exist in museum collections today, a testament to this incredible moment when art stepped off the wall and became a living breathing reality.

3 Comments

Starr Goodspeed

An excellent essay, lacking only a bit more about Diaghilev. A testament to collaboration and inspiration.

Marcella Simmons

Rosie, thank you! You have connected the dots in this insightful piece about this brilliant cast of characters. It is great to see the photos too. What a great way to start my day!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you both – glad you enjoyed reading this one!