Danger, Power and Seduction: Fabric in Romanticist Art

One of the most fascinating periods in art history, the Romanticist era of 19th century Europe and the United States opened the floodgate to new and unchartered realms of expression. Artists drifted away from reality into the fantastical, irrational wonders of the imagination, envisioning scenes filled with perilous danger, sublime beauty, and erotic seduction. Fabric was an essential tool that amplified these heightened, theatrical emotional states, billowing around grand portraits, creasing around naked flesh, or taking flight through a gale force wind.

Romanticist ideas were brewing amongst literary circles throughout late 18th and early 19th century Europe for decades before gradually spreading into the visual arts. English painter JMW Turner is often cited as one of the first pioneers of the Romanticist style, which he incorporated into his terrifying, awe-inducing scenes. While his focus was on exaggerating the dramatic, theatrical power of the landscape, fabric often made its way into his imagery as a manifestation of the human interaction with nature. In The Shipwreck, 1805, the ship’s sail in the foreground takes centre stage, pulled tautly and dramatically lit by moonlight, a potent symbol of man’s attempt to harness the insurmountable forces of the stormy night-time sea.

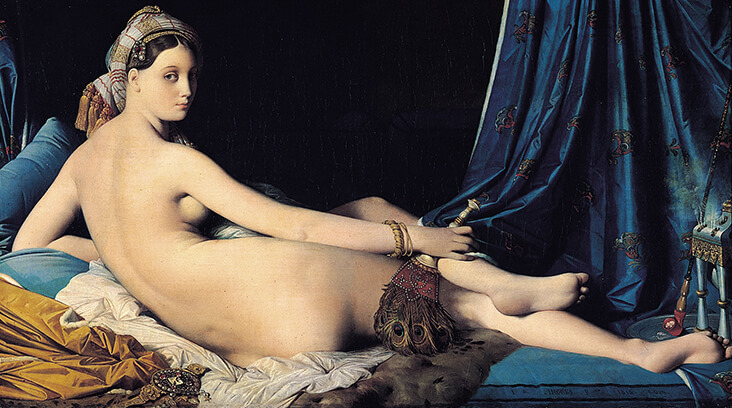

In France, Théodore Géricault, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix were among the first pioneers to experiment with and popularise Romanticist painting, often shocking the public with daring, confrontational or uncomfortable imagery. Ingres focussed on figurative subjects, particularly women set amidst sumptuously painted textiles that emphasised and enhanced their femininity. His controversial Grande Odalisque, 1814, takes influence from Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino, 1528, but instead situates an idealised young woman in a harem, conveying the rising cultural fascination with Orientalism. Sumptuous, indulgent textiles lift the scene into the realms of fantasy, with a heavy blue curtain glistening in the light and yellow bedding creasing into seductive folds near her naked body.

Ingres’ more traditional portraits also relied on fabric to illuminate his sitters; Baronne James de Rothschild, 1848, conveys one of the wealthiest women in Paris dressed in indulgent layers of pink satin lined with lace and decorative bows, sitting on a deep, wine-red velvet sofa. Her pink dress is the scene-stealer, rippling in and out of the light with an ostentatious complexity that mirrors the frivolity of her lavish lifestyle. Similarly, Ingres’ portrait of Louise de Broglie, Comtesse d’Haussonville, 1845 captures the eminent French essayist and biographer as a wilful, independent spirit, whose sharp, inquisitive eyes are reflected in the cascading folds of her shimmering lilac dress.

In contrast with the seductive, touchably real fabrics of Ingres, Delacroix ventured into dark, complex and sometimes morbid political scenes that reflected the turbulent times in which he was living. Liberty Leading the People, 1830, was made in response to the Parisian revolt in 1830, with a metaphorical ‘Liberty’ rising from a tangled mass of bodies below. Fabric was an essential aid in the theatricality of his storytelling, crumpling into dirty, worn down rags in the undergrowth, while above them the glowing yellow dress falling from Liberty’s body is the symbol of victorious triumph, topped by the French tricolor flag waving victoriously in the sky.

Like Ingres, Delacroix was fascinated by the Orient, and he made a life-changing visit to Morocco in 1832 which would have a marked influence on his future paintings. In contrast with many of his contemporaries, he chose not to paint an idealised Romantic vision of the East, focussing instead on violent, chaotic scenes of political or religious unrest. Convulsionists of Tangier, 1837-8, captures the frenzied activity of a religious street riot in Tangier with tangled swathes of fabric that ripple in and out of the blazing hot sunlight, while much like his ‘Liberty’, a green flag ripples through the breeze overhead as if ushering in order and peace.

Theodore Chasseriau was a former pupil of Ingres who came to exemplify the second generation of Romanticists emerging from France. His standout, career-defining showpiece was the immediately striking painting The Two Sisters, 1843, capturing his elder and younger sister posing as identical twins. Staging is everything here, as the women’s shimmering gold bodices are encased in dazzling, intricately embroidered red shawls, with black, austere parted hair standing out against an emerald green backdrop. When unveiled at the Paris Salon in 1843 critics were divided, with some calling it a “tour de force”, while others were bemused by the eerie image doubling effect. Chasseriau’s take on Romanticism was perhaps more understated than the art of his predecessors, yet this work’s strange, poetic melancholia was an undeniable marker of its time, a style that would go on to inspire the Symbolists, Pre-Raphaelites, and many more to come.

2 Comments

Nancy Gruber

Thank you! I love to read these articles that explore the connections between art and fabric. Truly fascinating!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you Nancy!