Glitz and Glamour: The Embroidered Textiles of Sarah Lipska

Polish artist and designer Sarah Lipska is an enigmatic figure, one whose life is only rarely written about in books and magazines. But hidden within the Met Museum in New York is a vast collection of samples from her embroidered textiles, each one adding an extra layer to the tapestry of her life. This collection of over 40 objects reveals the work of an exquisite maker who took months and years of time, care and dedication to make stunningly intricate embroideries from luxury fabrics and threads, producing textiles that now epitomise the glitz and glamour of the 1920s. These objects also reveal a maker who dissolved boundaries between fine art and design, revolutionising the art of embroidery and inspiring generations of artists and designers to come.

Although she would eventually make her name in 1920s Paris, Lipksa was originally born in Poland in 1882 to a family of Jewish heritage. Setting out to be an artist as a young adult, Lipska studied fine art at the School of Fine Arts in Warsaw from 1904 to 1907 and much of her early career was dominated by the production of paintings and sculptures.

A move to Paris in 1914 just before the outbreak of war would be career-defining, allowing Lipska to meet and mingle with a like-minded set of creative voices including Natalia Goncharova, Serge Diaghilev and Tamara de Lempicka. Inspired by the avant-garde artists around her she worked across a wide range of media, creating experimental paintings and sculptures that were exhibited across Paris.

In 1919 Lipska secured work designing sets and costumes for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, working alongside various other artists including Goncharova and Leon Bakst. Lipska’s designs featured bold colours and simplified patterns inspired by Cubist and Fauvist art, and their striking impact began earning her a reputation across Paris. Working with costume, in particular, opened Lipska’s eyes to the wondrous creative possibilities in clothing and textiles and throughout the 1920s she began working for renowned couture houses including Maison Myrbor and 4 Rue Belloni.

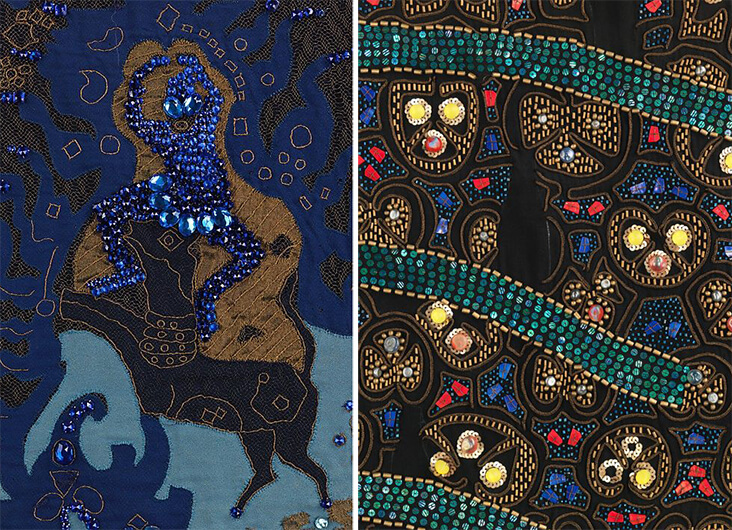

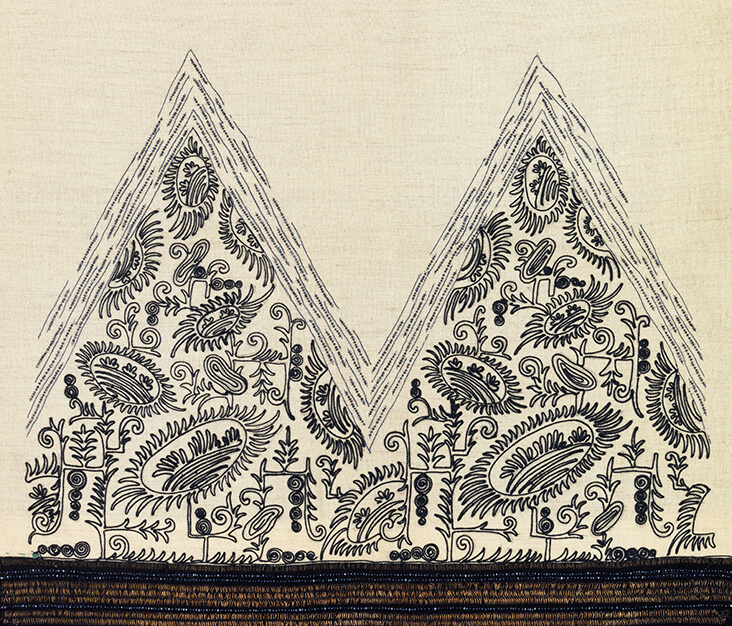

During this era, Lipska produced her own textile designs and realised them with hand-embroidered details. They were hugely varied, revealing the wide array of influences that inspired her. Much like her contemporary Goncharova, she fused ancient or folk-art influences with the simplified geometry of avant-garde art, emulating a widespread interest in the early 20th century with the unfiltered purity of earlier, pre-industrial cultures. Lipska often looked back to the ancient art of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire for ideas, emulating their decorative and indulgent repeat patterns, or integrating the ornate floral patterns and vivid colours of Polish folk art into her motifs. She fused these historical languages with the angular shapes and flattened forms of Cubist and Futurist art, and the clean modernism of Art Deco, producing a range of radical, forward-looking designs.

As an embroiderer Lipska was radical and experimental, weaving with metallic, silk, or brightly coloured thread onto a variety of fabrics ranging from silk and cotton to soft panels of leather. To create dense, tactile surfaces she often integrated different textures of thread into the same panel of fabric, or included indulgent elements oozing with glamour such as glass beads or rhinestones, which were brought to life in the flapper party clothes of the 1920s.

The popularity of Lipska’s embroideries launched her reputation amongst Parisian artistic circles and she continued to expand in an array of new directions, producing interior designs, furnishing fabrics and wallpapers for a series of prestigious clients in the decades that followed. In the 1930s Lipska produced a tapestry for the colonial exhibition in Paris, and throughout the remainder of her career, she continued to oscillate between art and design practices. Her legacy as an exquisite craftswoman who combined experimentation with dedication has undoubtedly shaped the nature of textile design since, from French fashion house Kenzo’s embroidered sweatshirts to German designer Markus Lupfer’s experimental, hand-worked textiles, and Ukrainian designer Vita Kin’s painstakingly detailed designs, proving just how powerful and long lasting her legacy continues to be.

2 Comments

Jo Asher

I love these essays you send. They are so well written and interesting. In the past women were restricted to expressing their art through very limited media- generally fabrics and usually something functional. But look at how glorious these ‘expressions’ are! Thank you!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the reply Jo – her work is so exquisite – I really enjoyed researching it!