Parachutes, Mohair and Silk: How Zika and Lida Ascher Transformed British Textiles

Zika and Lida Ascher were shape-shifting rulebreakers, who pushed the bounds of British fabric design in daring and unconventional new directions. Arriving in the UK at the outbreak of the Second World War, the young couple successfully redefined the bleak face of post-war British textiles throughout the 1940s with electrifying bursts of colour and life, which came to symbolise a new era of optimism and hope. The pair made a series of pioneering innovations, collaborating with the world’s leading artists on a series of iconic silk scarves and experimenting with unconventional fabrics including rayon, parachute nylon, silk, wool, mohair and cheesecloth, producing sumptuous designs that forever altered the fashion landscape.

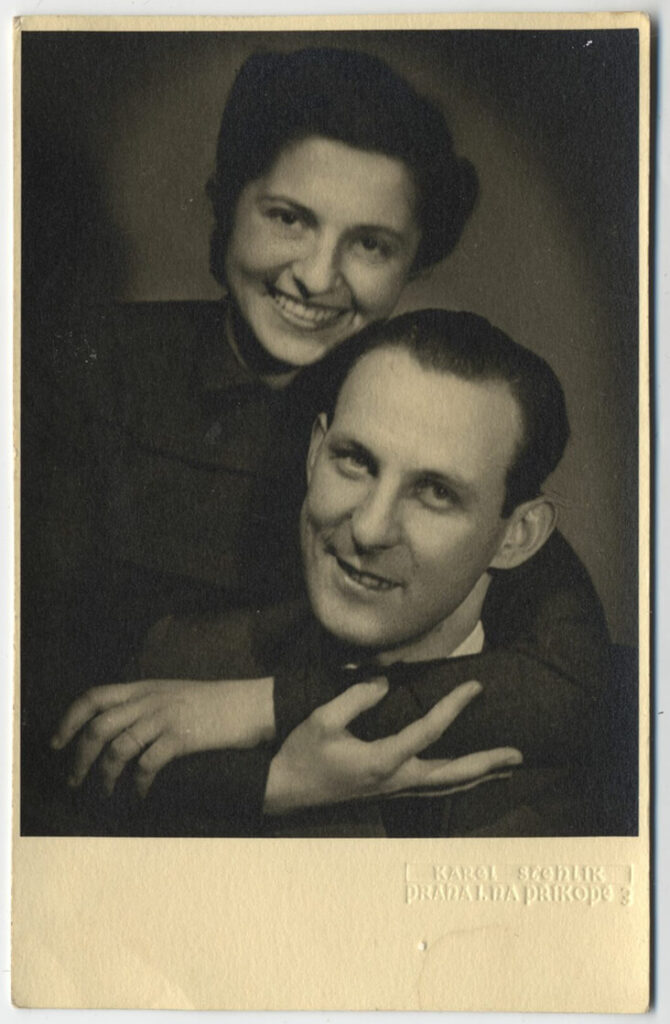

Zika Ascher was born to a wealthy Jewish family of textile manufacturers in Prague in 1910. A world champion skier in his youth, he was known as ‘the mad silkman’, a reference to his bravado on the ski slopes and his family’s fabric business. In a whirlwind romance, Ascher met and married the Czech aristocrat Lida Tydlitatova in 1939, just before the outbreak of war. They headed to Norway on honeymoon, only to discover that Hitler had annexed the Sudetenland and they could not return home. In a fortuitous twist of fate, the pair emigrated to London, setting up a new home together with help from members of the Ski Club of Great Britain.

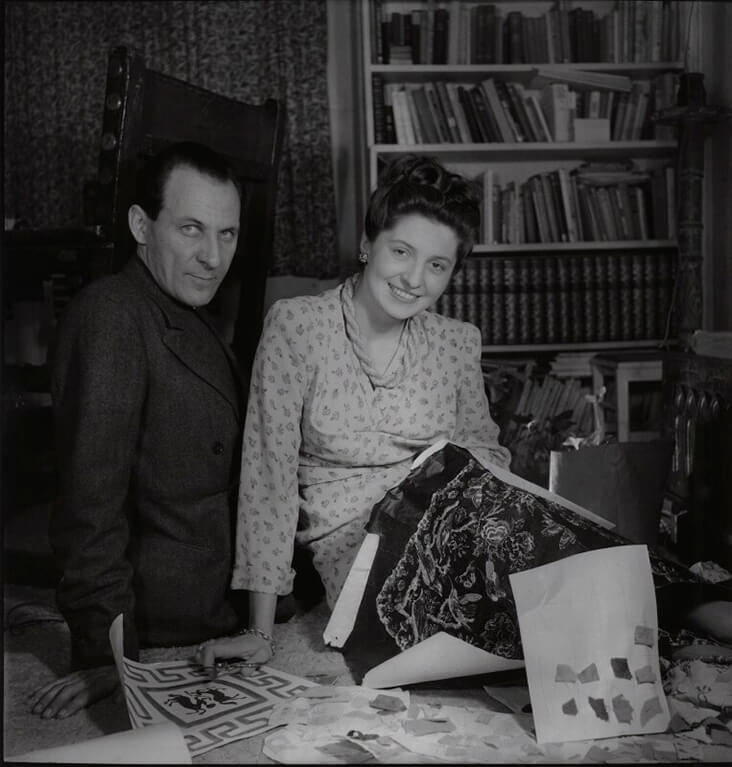

Times were hard in these early years; Zika’s son Peter recounts how their only possessions were “a few hundred pounds and Lida’s jewellery hidden in a sock.” Zika served in the British army, while it was Lida who first began designing fabrics with floral and calligraphy patterns. In 1942, the pair set up Ascher London Ltd., combining Ascher’s great knowledge of fabric dye, printing and manufacture gleaned from his family business, and Lida’s unmistakable eye for pattern design. Cotton and silk were rationed during wartime but the Ascher’s were inventive, adopting parachute nylon and rayon for an array of vividly bright, screen printed textiles. They also discovered the curious wonder of flimsy silk used for insulating electrical wiring, producing intricately patterned fabric that was used in a dress design for Princess Margaret.

Exhibition view of The Mad Silkman: Zika and Lida Ascher Textiles and Fashion, featuring fabric designed by Henry Moore (right) Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, image via Prague EU

Three years later, in 1945, Zika struck gold with an ingenious idea, inviting the world’s leading artists to design artworks for printing onto square silk scarves. With his quietly persuasive nature, he coaxed an impressive roster of artists to join in, including Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore, Ivon Hitchens, and Henri Matisse, to name just a few. Ludicrously popular, the silk scarves became known as “the Ascher square” and were snapped up by buyers across the country, enlivening the British wardrobe with wearable works of art. Part of the appeal was Zika Ascher’s exacting attention to detail and high standards production; he insisted on only using cloth woven in Britain, and worked closely with artists to achieve as close a likeness as possible to their original work. Today these scarves are highly sought-after collector’s items, and in recent years some have even been reissued for a new audience.

Following on the success of their collaborative scarves, the Aschers were able to set up new, larger premises in the late 1940s, where they continued to produce accent wearable silks in collaboration with artists from across Europe. By the 1970s, popularity was so high they were producing upwards of 2,000 scarves a day to keep up with demand.

Three standing figures, 1944 Henry Moore © Peter Ascher Ascher Family Archive, image via The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague

The Aschers branched out into floral motifs throughout the 1950s, designing and printing fabrics featuring hummingbirds, flowers, radishes and bees, breathing exuberant life into the British fashion industry and attracting high profile designers including Christian Dior, Cristobel Balenciaga and Yves Saint-Laurent. In the 1960s Zika and Lida made further pioneering designs with brilliantly coloured and patterned mohair in acid sharp shades of orange and pink, stunning audiences into disbelief with a fabric described by American Vogue as “soft, thick, weightless as a moth’s wing, spun together out of mohair, nylon and wool…”

In the decades that followed the Aschers continued to experiment with bold patterns and unusual fabrics, including the humble cheesecloth, along with chenille, plastic-coated printed cotton and even paper-based textiles, taking an ever-expanding array of experimental risks. In 2019, an impressive retrospective publication The Mad Silkman: Zika and Lida Ascher Textiles and Fashion, was written by Konstantina Hlaváckova with assistance from the Aschers’ son Peter and accompanied by an exhibition at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, paying a lasting tribute to the huge, and unmistakable contribution his mother and father made to British fashion.

4 Comments

Deborah Carver

While looking for info about Virginia Woolf for bookclub a few months ago I noticed this photo of her taken in what looks like a slipcovered club chair. The fabric is fabulous and I’d love to learn who designed it and what decade such design was popular. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/holding-virginia-woolf-in-your-hands

I think it would be lovely in a linen/cotton blend.

Rosie Lesso

I see what you mean – the chair fabric looks amazing! I’m not sure who the designer would be but I will look into it and see if I can find anything. I wonder what colours it would have been printed in…

Carol Buxton

Thank you for your various snapshots into the history of fabrics and its designers. I especially appreciate this article on the Aschers as my mother was Czech, born in 1921, and left Prague in 1947 when she married my father, an American Pan American pilot. Our family has many stories from before, during, and after World War II, when first the Nazis and then the Russian Communists occupied Czechoslovakia.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the comment Carol! It sounds like your family have some fascinating stories to tell…