Anni Albers: Past, Present and Future

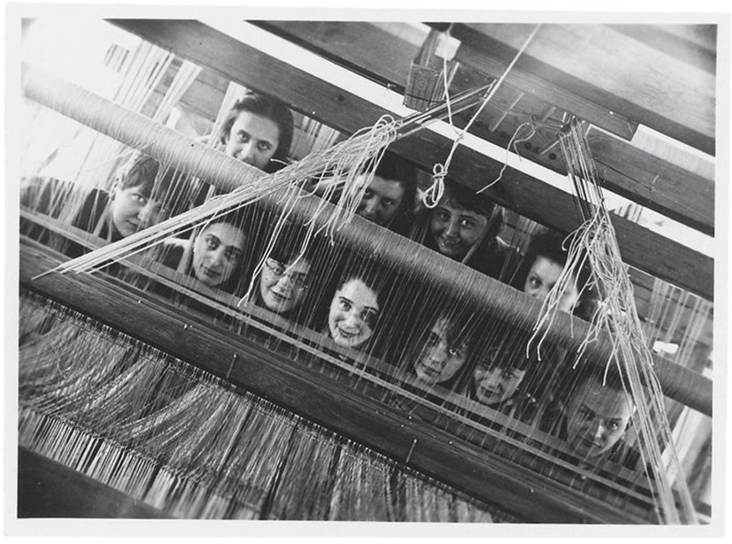

Anni Albers in her weaving studio at Black Mountain College, 1937/ Photo by Helen M. Post Modley/ Courtesy of Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina

When it comes to 20th century pioneers, Anni Albers is the quietly tenacious artist who defied all expectations, blending technical mastery with Modernist abstraction to revolutionise the ancient craft of weaving into an art form in its own right. Pointing to the rigid divisions between fine and applied arts in her later years, she wrote, “I find that when work is made with threads, it’s considered craft; when it’s on paper, its considered art.” At a time when women’s contribution to the arts is being revisited, Albers’ hugely prolific practice has been celebrated with several recent large scale retrospectives, confirming her position as one of the most innovative and influential artists of the 20th century, instrumental in defining the term ‘textile art’, leading the way for the world’s artists and designers of the future.

Born Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann in Berlin in 1899 to a wealthy family, the artist’s first ambition was to be a painter. She began studying at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg in 1919, but left after only two months. After seeing a flier for the Bauhaus in Weimar, she later remembered, “I thought, that looks more like it, so this is what I tried.” Fleischmann entered the school in 1922, just three years after its foundation. In the wake of the First World War the Bauhaus had an idealistic ambition to make society great again by integrating high-quality design into everyday life, bringing art to the masses to improve working and living standards for all. Although Bauhaus maintained an apolitical position, its core belief lied in the power of geometry to instill order amidst the political chaos and destruction of war. Founded by Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus encouraged the union of practical craftsmanship with creative imagination through structured workshops taught by some of the world’s leading artists and designers such as the Russian painter, Wassily Kandinsky and the American German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Despite its notorious lack of funds, the Bauhaus quickly gained an international reputation as a leading centre for art and design.

Life at the Bauhaus, 1928/ Photographer unknown © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

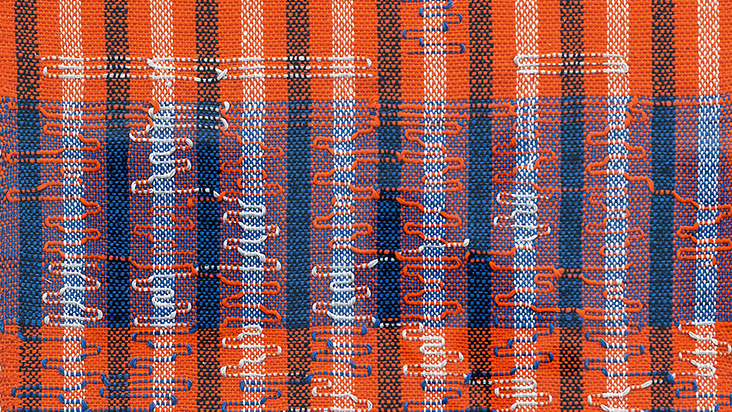

At Bauhaus Albers was unfazed by the straw mattresses, tiny rooms and weekly cold, communal baths and yet she was taken aback by the supposedly progressive attitude towards women, who were banned from “heavy craft areas”, including architecture, carpentry, metalwork and painting, directed instead towards subjects that encouraged decoration, including weaving, colloquially known as the “women’s workshop” and bookbinding. Anni Albers said she ‘went into weaving unenthusiastically, as merely the least objectionable choice’, but ‘gradually threads caught my imagination.’ Albers quickly stepped away from the “beautiful pillowcases and tablecloths” of her peers towards what she called “textile engineering”, she quickly mastered skills in double and jacquard looming, producing huge, intricately crafted wall hangings and upholsteries with a striking visual impact. She soon began to see weaving as the ideal Modernist medium, with its inherent geometric patterns and grids that could be offset with haptic, tactile hand-made qualities, while also remaining rooted in ancient traditions which connected with society at a deeper level.

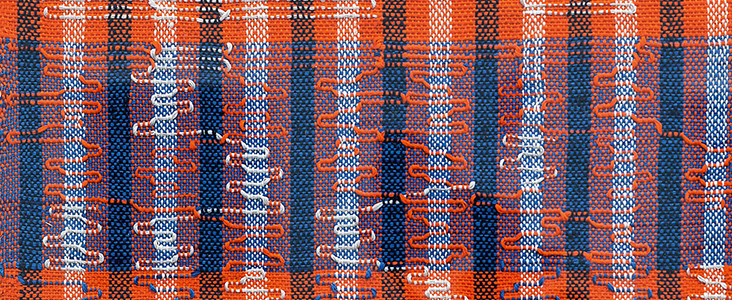

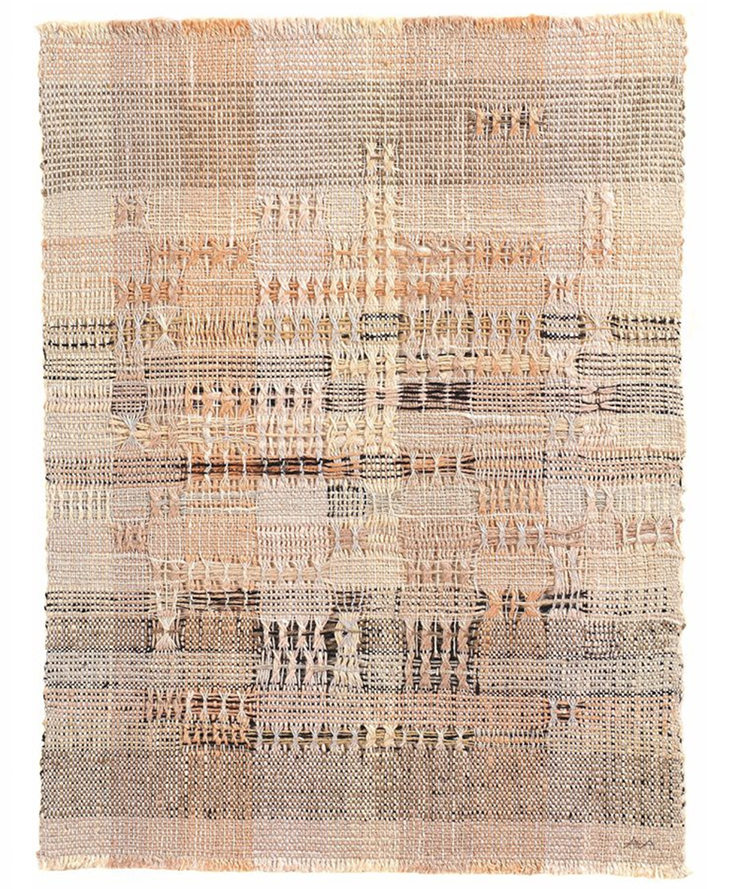

Her striking designs were influenced by the most avant-garde geometric patterns of the time, combining unconventional materials including cellophane, raffia, copper chenille, lurex, corn, grass, horse hair and string with cotton and linen, merging ancient hand weaving techniques with forward-looking ideas and materials, often in a muted, pared down colour scheme. Writer Charles Darwent described her process as “building by stealth” when she began to create site specific wall hangings that could absorb sound, reflect light and add structure or form to architectural spaces.

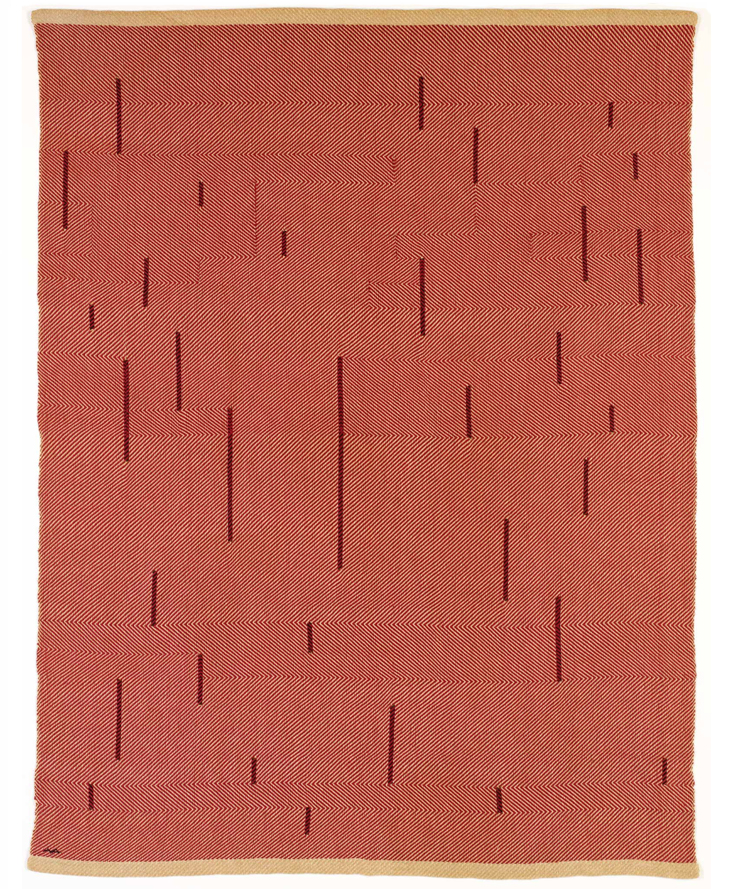

In 1925 she married the painter Josef Albers, a glass artist who was also studying at the Bauhaus. The school moved to Dessau in 1926, where Josef became an influential tutor and Anni Albers continued her weaving diploma in the new premises, graduating in 1930. She produced sound proof wall coverings for the walls of an auditorium at the ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau designed by Hannes Meyer as her diploma work, in which black and white threads were interwoven with light reflecting cellophane and chenille coatings to muffle sound. Not long after, she began teaching in the weaving school, quickly rising the ranks to become the new director of the textile department, reforming the weaving workshops into a site for experimentation and artistic expression.

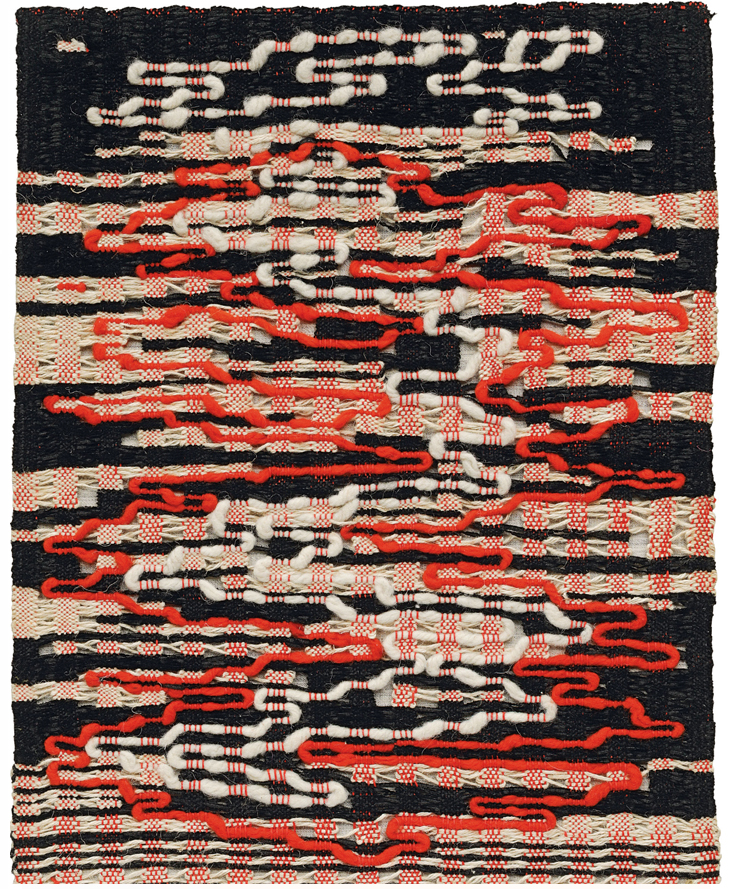

With the rise of Nazism the Bauhaus was forced to close in 1933. Josef and Anni Albers emigrated to the United States, where they were both offered teaching work at the small, newly founded progressive art school Black Mountain College in North Carolina, as recommended by architect Philip Johnson. There they found a close knit community in a rural setting that encouraged the free exchange of ideas. Albers established a weaving workshop, encouraging students to use everyday materials, to weave without a loom using simple patterns and textures, or use South American back-strap looms, investing a greater sense of tactile materiality into their work. She continued to expand her own ideas, which she exhibited widely across the United States, including her revolutionary “pictorial weavings”, painstakingly hand-woven textiles in thoughtful, somber colours which were designed to be hung on the wall as works of art rather than functioning objects, saying, “…let threads… find a form themselves to no other end than their own orchestration, not to be sat on, walked on, only to be looked at.”

Albers also produced designs for commercial production, which she distinguished from her hand-woven works of art. In 1948, Gropius commissioned Albers to design bedspreads, drapery and dividing curtains for common areas and dorms at his Harvard Graduate Centre in Massachusetts. At Black Mountain College Albers befriended her former student Alex Reed and the pair collaborated on a series of anti-luxury jewelry inspired by the natural materials she saw in the ancient jewelry of Monte Alban, made from industrialised objects including paperclips, washers, screws and hair clips, realised with a surprising delicacy.

Albers became the first textile artist to be awarded a solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1949, revealing the full scope of her innovative practice over the last several decades. The same year she and Josef left Black mountain and moved to Connecticut to live in a house-turned-studio, where Albers incorporated a hand-loom technique known as leno or gauze weave, where “vertical warp threads twist over each other around the horizontal weft threads.” In 1950 Albers designed a drapery interwoven with metallic thread to create light reflecting qualities for Philip Johnson’s Rockefeller Guest House, a Manhattan townhouse filled with artworks belonging to the Rockefeller family.

Together Josef and Anni made regular trips to Mexico throughout the 1950s, entranced by the exotic patterns and rich, earthy colours of Peruvian and Andean textiles. Albers was particularly fascinated by the use of textile in Peru as their only form of visual language until the 16th century, writing, “The textiles of ancient Peru are to my mind the most imaginative textile inventions in existence. Their language was textile and it was a most articulate language…” In her own practice, she sought ways to integrate a similar form of visual code that could be slowly unraveled like a text in foreign language, investing a deep sense of weight and history into her Modernist designs.

Albers teamed up with the furniture magnate Florence Knoll in 1951, forging a collaborative relationship which would last over 30 years, designing many furnishing fabrics that are still in production today. In 1971, the Alberses established the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation as a platform encouraging collaborative projects, including work with the British rug and fabric printer Christopher Farr Cloth.

Anni Albers, TR I, 1970, lithograph/ Second Movement V, 1978, etching and aquatint/ Anni Albers Do I, 1973, screenprint

Albers expanded her ideas in two theoretical publications in the 1950s, publishing On Designing in 1959, and On Weaving in 1965. In the latter she wrote a chapter titled Tactile Sensibility, expressing her concern that our culture is losing touch with our need for the tactile sense, writing “…we touch things to assure ourselves of reality.” In 1965 she also produced one of her most evocative weaving commissions to date, a memorial for The Jewish Museum to commemorate those who died in the Holocaust. This deeply contemplative work was 6 feet wide, a reference to the 6 million people who died, while a flickering weave echoed the Jewish notion of ‘tikkun’, or ‘social repair’. Struck with arthritis, Albers was forced to abandon her beloved loom in her later years, spending the last few decades of her career realising similar ideas in abstract printmaking.

Anni Albers Six Prayers 1966-1967 The Jewish Museum, New York, Gift of the Albert A. List Family, JM 149-72.1-6 © 2018

As with many women of her generation, Anni Albers’ work has often been treated as less important than the art of her husband, Josef Albers, an immensely influential artist of his contemporaries. Despite the success she achieved in her lifetime, she often felt her practice was treated as inferior to the more traditional fine arts being produced at the time, an issue she wrestled with throughout her career. Earlier this year, Tate Britain displayed a large retrospective to celebrate her expansive and prolific legacy, delving into her rich archive to reveal the full scope of her unique vision, as artist, designer, teacher and collaborator.

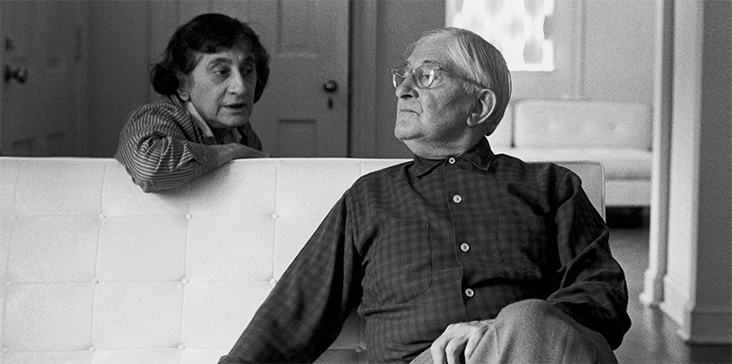

Anni and Josef Albers photographed at home by Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1968. Photo © Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

Albers’ influence continues to be felt today in the worlds of art and fashion. Artists who experiment with similar industrial materials include Karla Black and Phyllida Barlow, while the tactile qualities, geometric designs and blending of old and new she brought into the world of weaving are still increasingly popular today, with designers including Roksanda Ilincic, Mary Katrantzou, Duro Olowu, Grace Wales Bonner, Nadege Vanhee-Cybuski and Paul Smith all citing her as an ongoing source of inspiration. Countless designers continue to collaborate with the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, keeping their ideas alive for a new generation to come. Ilincic summed up the magnitude of Albers’ legacy: “I’ve always been drawn to her status as a woman within the Bauhaus. Women were expected to work on weaving and tapestry, but she tore up the perception that applied arts categories can’t be worthy of our admiration or high status.”

12 Comments

Janet Anderson

Love these articles. I learn so much about art in all forms. Thank you.

Hg Fuller

I concur with others’ comments about these wonderful educational articles. They add such a depth and enjoyment to this ancient human art. Please continue.

Leatrice Linden

I learned to weave in 1963 on Anni Albee’s loom that is pictured in the beginning of the article. My teacher was Jerri True from North Carolina, I don’t know how she came into possession of this loom but it was a magical experience. Anni Albers and Lenore Tawney were my inspirations for becoming a fiber artist and my works reflects their philosophy Let’s the threads speak

Carol Koch

These articles on textile designers have become something I look forward to. I am transitioning my career and have always felt this would be my next area to explore.

Carol Frey

This series of articles is wonderful and this one I particularly appreciate.

Susan Macleod

Fascinating article. I plan to play with some of her techniques on my new to me mini tapestry loom.

AL Golden

Great article.

PS: Rockefeller only has two “r”.

Epeemom InTX

Our swatch swap group in our weaving guild just finished a year of Anni Albers study and weaving. I will forward to our members!

Melissa Brown

Lovely to see words about Annie Albers. I was most fortunate to meet her and study her work years ago.

Oksana Karpushin

Thank you so much! We are happy to hear you are enjoying them 🙂

Susan Johnson

these ‘art history’ reports are wonderful!

Thank you so much for them.

Susan

Rosie Lesso

Thank you Susan, that’s great to hear you are enjoying them!