Power and Purpose: The History of African American Quilting

“I do view African-American quilting as a genre, just like traditional quilts, art quilts, modern quilts. Our quilts are just a little bit different.” O.V. Brantley, Founder of Atlanta Quilt Festival

Quilting is a vital strand of African American culture, telling vividly complex stories of pain, oppression, freedom, and power. There is no single unifying style that defines African American quilts – they are as unique and individual as their makers – but certain similarities have been observed by quilt historians over the centuries that are hard to ignore, such as asymmetric designs, large-scale patterns, and wonderfully rich story quilts, to name a few. Made predominantly by women and passed down through the generations since the early days of America, some quilts celebrate and revive the bold patterns of ancient African culture, while others reflect on personal or historical stories of struggle and emancipation. Thanks to a growing body of research across galleries worldwide the complex and diverse history of African American quilting is becoming more widely understood today than ever before, while the political agency and visual impact of the medium is being embraced by a generation of contemporary makers. In this new series, we will trace the history of African American quilts throughout the development of America up to the present day, revealing the powerful sense of purpose, community, and communication embedded in this most historical of art forms.

In early America quilting was both functional and artistic, forming an essential need for warmth and comfort as much as interior decoration. African American slaves were often tasked to spin, weave, sew and applique quilts for their mistresses. Research reveals how these highly skilled makers would also make bedding for their own families; fabrics for personal use were scarce but these women were highly resourceful, turning scraps of “throw away” goods such as faded or worn clothing and food sacks into stunningly complex designs. Patterns they developed included Sawtooth, Durnkard’s Path, Railroad Crossing, Tree of Paradise, Ocean Wave, Feathered Star and Nine Patch. Another common practice was to create “string quilts”, in which thin scraps of leftover fabric were stitched together to create larger panels that could then be sewn into a quilt.

It is also thought slave families produced quilts with hidden coded messages, particularly during the Underground Railroad, to reveal safe houses for runaway slaves, or to communicate coded messages to one another. One of the most prominent quiltmakers to emerge from this era was Harriet Powers, who was born into slavery and survived the Civil War. Known today as the “mother of African American quilting”, her world-renowned “story quilts”, wove Biblical or secular tales with a moralising message into their core and they are among the most celebrated works of art in history. Powers was one of the first to recognise the invisible barrier between quilting and art practice and her influence continues to be felt today.

Following the American Civil War, many African American women found employment in farms and cities. Increasing prosperity and less time meant quilting took a back burner for the younger generations, while those facing retirement continued with the practice, sharing quilt patterns and designs amongst community groups and learning new ideas from magazines. The practice of making quilts shifted from necessity to pastime, offering greater room for personal freedom and expression. One particularly popular motif during this time and throughout the early twentieth century was the Pine Cone or Pine Burr Quilt made from a series of tiny overlapping triangles arranged into a circular pattern to resemble the look of a pine cone.

The much-celebrated quilting community of Gees Bend in a remote region of Alabama emerged in the 1930s, where a close-knit group of African Americans established their own distinctive approach to making quilts. Though individual styles varied, by the 1960s the group had earned a wide following for their vivid colours, asymmetric designs, and innovative modernist arrangements of abstract shapes. Such was the ingenuity and success of the original group, by the 1960s they had earned an international following, and they are still going strong today.

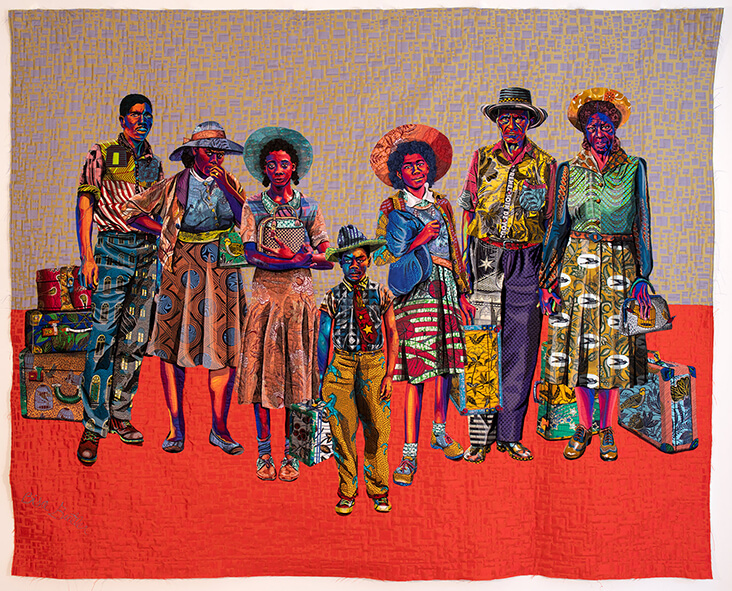

In contemporary times many African American women are keen to adopt quilting styles that reflect upon both their rich visual heritage and the many stories of their complex and troubled past, lending their work striking visuals and a political urgency, from Faith Ringgold and Marla Jackson to Sherry Shine and Bisa Butler. African American quilt historian Cuesta Benberry also observes a rising trend towards celebrating the unique African strands of their past in these artists and many more, noting, “Quilters are making conscious and deliberate efforts to incorporate African themes in their works. Some persons begin by using African textiles in their quilts; others take courses in art history or engage in ambitious projects such as researching design tradition in specific African tribes.”

3 Comments

Pingback:

These 17 African Traditions Built Modern America - Most People Don't Know - Back in Time TodayChristina Daily

Rosie, you have such compelling and fasinating stories to share about the fiber arts . Thank you.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the comment – there are so many amazing stories out there to uncover!