Indigo in India: The Colour of Desire

“The origin of taste, of fabric printing is India.” Georg Stark, contemporary textile artist

With a name that means ‘the Indian’ or ‘from India’, the colour indigo is woven tightly into Indian history. The first nation to turn indigo production into an international trade, ancient India produced some of the finest and most luxurious indigo dyes and fabrics of all time. Throughout early civilizations Indian indigo products became highly desirable and much fought over commodities around the world, eventually sparking bitter, brutal and destructive conflicts. Because of this international desire the colour also became highly prized within ancient India, colouring fabrics reserved for only the wealthiest members of society.

Indigo production in India can be traced back as early as the 4th century BC. Here the indigofera tinctoria plant was found in abundance, yet the Indian process of soaking, fermenting and drying indigo leaves was a complex and time-consuming process which was developed over the centuries into a fine art. As the desire for Indian indigo increased over the centuries, their masterful techniques for creating such luxurious and intense shades of blue became a tightly guarded secret, passed from one family to another through the generations.

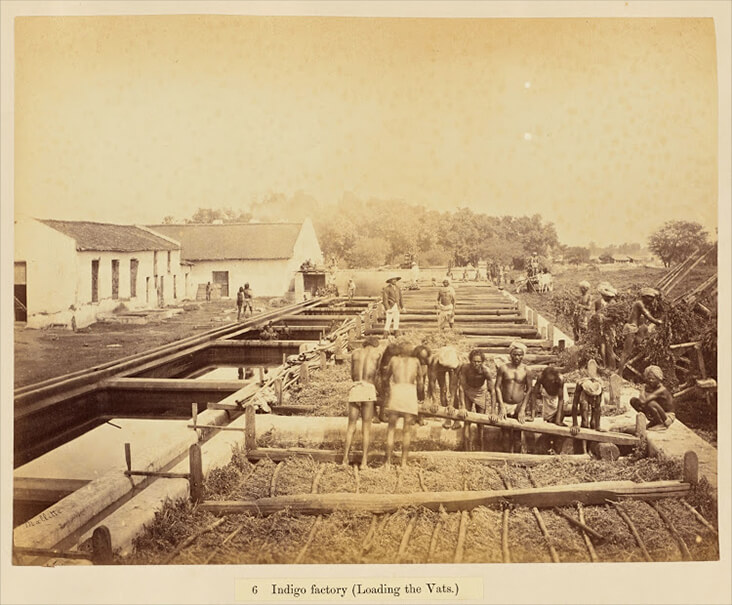

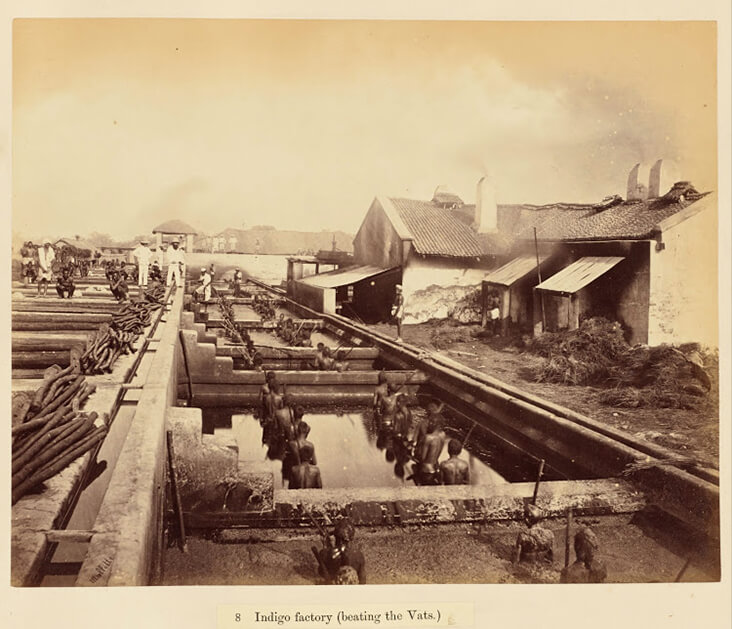

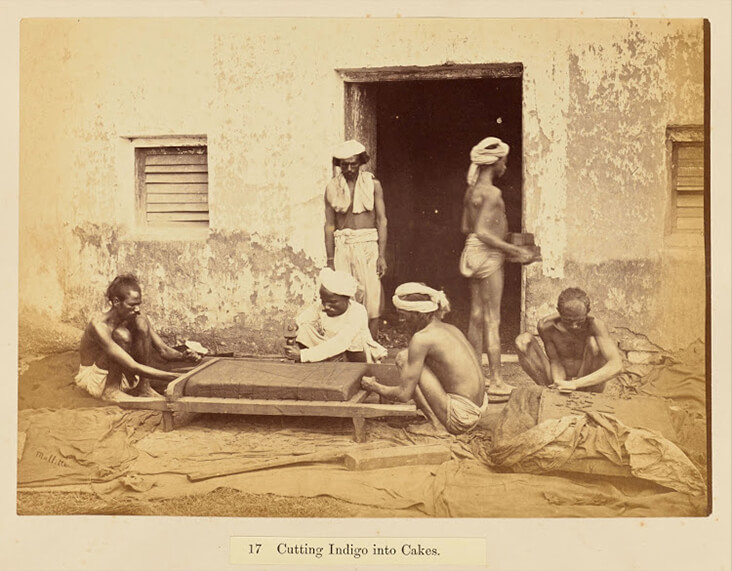

It is thought the ancient technique for creating indigo in India was similar to that of various regions at the time, and one which is still practised in a small number of natural indigo farms in India today. First, the leaves of the indigofera tinctoria plant are gathered in huge bundles, before being soaked and fermented in water and lye. The leaves are then removed, leaving indigo white in the water, which is oxidised and turns an intense shade of blue. This watery substance is whisked and a blue colour settles, forming a watery clay which is heated or sundried into dye cakes.

These indigo cakes were a popular commodity on the trans-Saharan trade to the Mediterranean, where Greeks and Romans valued them higher than gold. Indian fabrics dyed with these intense colour cakes had a vibrant, steadfast colour and richness of texture that was unrivalled; again, the secret processes for retaining colour within Indian Indigo without using a mordant were hidden, making their products all the more desirable.

The city of Agra in India was the main centre for indigo production, where various shades of blue fabric were made – the most popular with the western market were known as ‘Bayana’ and ‘Agra.’ ‘Sarkej’, from the city of Ahmedabad also became highly desirable in ancient times. The fine fabrics made in this dark, intense shade of blue were reserved for royalty or those with the most political power and authority.

As well as producing pure, single coloured indigo fabrics in cotton and silk, India also became well known for their lavish and intricate textile designs, often combining indigo blue with various other locally made colours including reds and yellows. Resist dyeing techniques were used by painting wax or a mud and lime paste onto fabric before dyeing. Block printed designs from highly detailed stamps were sometimes applied to dyed fabric, as were passages of exquisite embroidery. Popular motifs in Indian textiles were flowers, plant formations, architectural shapes and Islamic-inspired designs made from geometric repeat patterns.

Indian indigo developed closer ties with the West in the late 15th century when the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to India that allowed trade to pass through India, the Spice Islands, China and Japan into Europe. During this period indigo truly became one of the most valued exports amongst European merchants, which even led many to call the colour “blue gold.” India could barely keep up with demand and their indigo production became part of a tyrannical and brutal regime. These issues led to the development of the similarly toned woad dye in Europe, which had neither the staying power or the intensity of Indian indigo. To protect their woad production, French and Norwegian officials even banned Indian indigo, tarnishing its reputation by calling it the “devil’s dye.”

The creation of synthetic indigo dye in the 19th century unravelled India’s indigo trade and it only the rare few who continue to practice this fine art of dye and fabric production today. But as the contemporary German artist and textile designer Georg Stark points out, natural, Indian indigo has a unique richness and complexity with red and purple undertones that is impossible to recreate industrially. This quality is something which is slowly beginning to attract a new generation of designers who believe, like Stark, “Handmade fabrics will always have special status.”

2 Comments

Christina Daily

This article is a lovely tribute to Indigo. Anyone who has tended an indigo dye vat understands the complexity of this art. I especially like the old photographs.

I see several articles on indigo. Have you ever been or seen the dye pits on the Jos Plateau, ner the city of Jos, in Nigeria?

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the comment Christina! Masha did an amazing job hunting out the beautiful vintage photographs. I have never seen an indigo dye pit in person, but hopefully one day in the future. I don’t know much about the dye pits at Jos Plateau but do share more info or images if you have them – it would be fascinating to find out more!