Indigo in Africa: An Indigenous Craft

Indigo dye is soaked deep into Africa, where some of the finest fabrics in the world have been made. The exquisite skills required to produce such high-quality fabrics has been passed down from one generation to the next for at least 700 years, making African indigo production one of the oldest industries in existence. From the traditional Yoruba people of West Africa to the stripweavers of Kong, indigo has been adopted by indigenous people from all across Africa, each developing their own highly distinctive processes and designs that remain in place to this day.

No one really knows exactly when indigo production began in Africa, but the dye pits of Kofar Mata in Kano, North West Nigeria, offer us some clues. One of the oldest dye pits still in existence today, the sign above the entrance gate reads 1498, although the renowned Moroccan traveller Ibn Battutah visited Kano in the 14th century and noted his wonder at the colour alchemy of their practices, proving they had already been in existence long before then.

In Kano they still practice the traditional indigo practice of gathering leaves, flowers and stems from either the indigofera or lonchocarpus cyanescens plants, which are ground together into a pulp in a wooden mortar and left to dry in the sun for two or three days. Meanwhile in dye pits a solution of water and hardwood ash is left in the sun, to which the indigo balls are later added, followed by cotton cloth which is submerged for two or three days. After being removed, the fabric is hung up and left to oxidise before it is ready for use.

But beyond Kano, variations in the dyeing technique have evolved and continue to be practiced, resulting in different hues of fabric. In the Ivory Coast, for example, bark from the Morinda tree is added to the dye pits, which is said to contribute to the fermentation process and thereby create a richer shade of blue with an aubergine cast. Across various areas of West Africa, the tradition of beating indigo cloth with wooden tools after dyeing has been practiced for hundreds of years, a process which presses the fabric and lends it a highly desirable satin sheen. Some practitioners in areas of West Africa would also beat additional indigo into the dry, dyed cloth to create an even darker, denser colour.

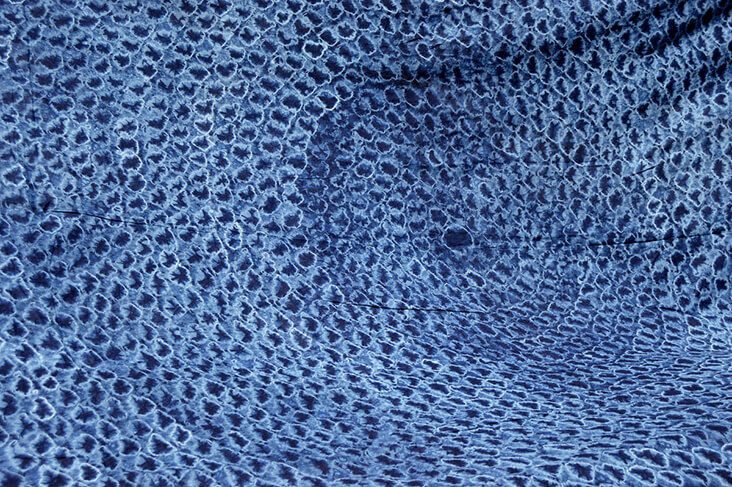

As well as producing a great variety of hues across Africa, patterns and textures of African indigo textiles are particular to certain areas. Some of the most famous textiles of Africa have been made by the Yoruba people of southern Nigeria, who are well-known for their deeply entrenched indigo traditions, as well as their intricate, decorative patterns that involve several different resist techniques. Two of the most popular amongst their communities are adire oniko (tied resist) and adire alabare (stitch resist). The former is a variation on the tie dye, or batik, tradition, in which fabric is folded into a pattern and tied together with stones, twigs, sticks and other natural elements to produce a huge variety of spontaneous repeat patterns.

Adire alabare, or stitch resist, is instead a far more intricate process in which dyers fold cloth into a symmetrical pattern, to which stitching with a raphia thread is added to resist the indigo dye. After dyeing this stitching is removed from the fabric to reveal beautifully intricate areas of patterning. Carrying out these techniques is a painstaking process completed entirely by hand, while the artisan has to take care not to rip the thin shirting cloth used in the process. End results are masterful, with dazzling areas of geometric repeat pattern adorning the deep blue fabric and transforming it into a work of art.

Starch resist patterning, or adire eleko is a more contemporary development that emerged during the 20th century, again from the hugely prolific region of Yoruba, with designers applying a starch made from cassava flour to one side of a cloth backdrop, either freehand or through a stencil. Patterns have varied hugely over the years, with many featuring lizards, birds, or landmarks in ornate symmetrical designs, while the natural variations in blue tones lend the fabrics a naturally hand-made, organic feel.

Sankofa Theater choreographer and creative director Kibibi Ajanku fell in love with traditional indigo dyeing in The Gambia in West Africa

Stitch-resist fabrics were also popular in Mali, with the Mandinka groups of southern Mali, eastern Guinea and the northern Ivory Coast particularly known for producing highly detailed cloths with exquisite attention to detail. Some are so intricate that they are recognised by today’s museums as an important branch of embroidery. Another technique practiced by the Baule tribe of West Africa was the deeply complex process of ikat, in which threads are tie dyed before the weaving process and are then lined up on a loom by a weaver to form a pattern, before being woven.

Stripweaving was also a popular technique in many regions of Africa, where fabrics are woven from indigo dyed cotton thread and sewn together into strips, before being decorated with finely detailed areas in white cotton. The exact origins of the technique are unknown, although by the 18th century highly detailed strip weaves had become a trademark product of Kong, in the present-day Ivory Coast. Such was the wealth of the region during this period due to the peak of the gold trade, the king and members of the African court were able to commission the most skilled artisans to create sumptuous, densely detailed stripweaves for both clothing and interior décor.

In recent times, the London based trio of designers known as the 419 Collective have integrated African indigo fabric made in Kofar Mata into their sleek, refined menswear. One-third of the group is Daniel Olatunji, who find a rare, unfiltered beauty in these naturally, made traditional fabrics, observing how “because the process is done by hand from start to finish the fabric is full of these irregularities that are so beautiful.” He adds, “… the entire process is natural as it existed long before most chemicals were introduced into fabric production.”

One Comment

Lael Sorensen-Boyer

I love learning about these processes! Very interesting. Thank you!