Art, Activism and Protest: The Arresting Imagery of Faith Ringgold

“I want the story to be told so that people understand what’s going on.”

Above all else, Faith Ringgold is an avid, entrancing storyteller, weaving the darker side of African American history into her richly complex works of art. Though her practice spans a broad range of media, she is perhaps best known for her story quilts, which merge the ancient, traditional craft with stories that address America’s divided politics, confronting issues that many still shy away from. Ringgold argues that real change only happens when we are fully prepared to acknowledge and learn from the mistakes of the past, and art can be a powerful catalyst in allowing this to happen. “One can find beauty in horror that you can share through your art and ideally effect change,” she writes.

Faith Ringgold at her dining table in Englewood, N.J., surrounded by her work “California Dah #3, 1983

Ringgold was born in New York in 1930. Her minster father and fashion designer mother opened up their home to a wide array of family and friends, who would sit around the dining table telling endless stories that fascinated the young Ringgold. “I had the benefit of a great oral tradition told in many ways by a diverse group of people where I had the chance to learn about my past and my family’s history,” she remembers fondly. Such stories were often laced with uncomfortable truths that did not escape Ringgold’s inquisitive ear, ones she would stow away for a later day.

Quilting was also a great family tradition that had been passed down through the generations; Ringgold’s grandmother and great grandmother, both former slaves, had taught Ringgold’s mother the craft, and she, too passed the skill onto her daughter. It was quilting’s multi-functional purpose that particularly fascinated Ringgold, as a form of communication, preservation, community, and warmth, qualities which she would integrate into her art as an adult.

As Ringgold grew up, she witnessed the Harlem Renaissance rising around her, as great, pioneering African Americans came to prominence including James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, Sonny Rollins and Aaron Douglass – ignited by their example, Ringgold saw the world opening up before her. But as an art student at the City College of New York in the 1950s, Ringgold soon became aware of how rife racism and sexism still were. Encouraged away from fine art into art education (fine art was for men, she was told), the course material was Euro-centric and focussed on white, male artists. Through the art of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Ringgold found the way back into her African heritage, embracing the same language of bold, enlivened colours and flattened simplified forms. Even so, after graduating, Ringgold’s semi-abstract landscapes failed to attract attention. All around her, racial tensions were turning into violent riots, and it was New York gallerist Ruth White who first gently nudged Ringgold towards, not away, from the conflicts.

American People Series #19: U. S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, Faith Ringgold, 1967

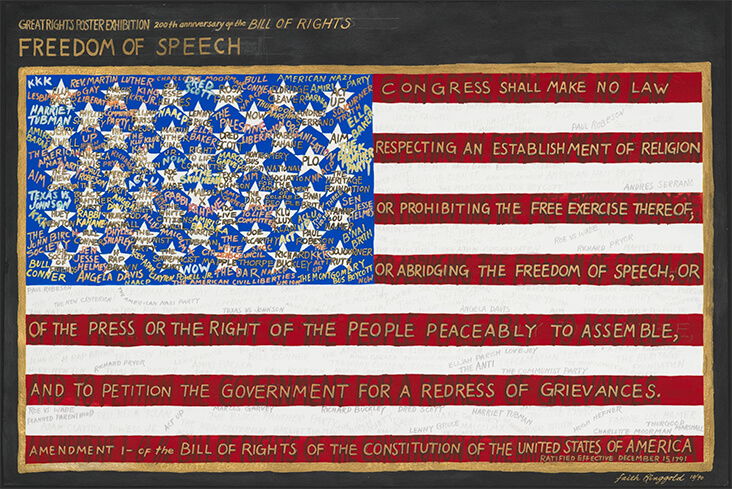

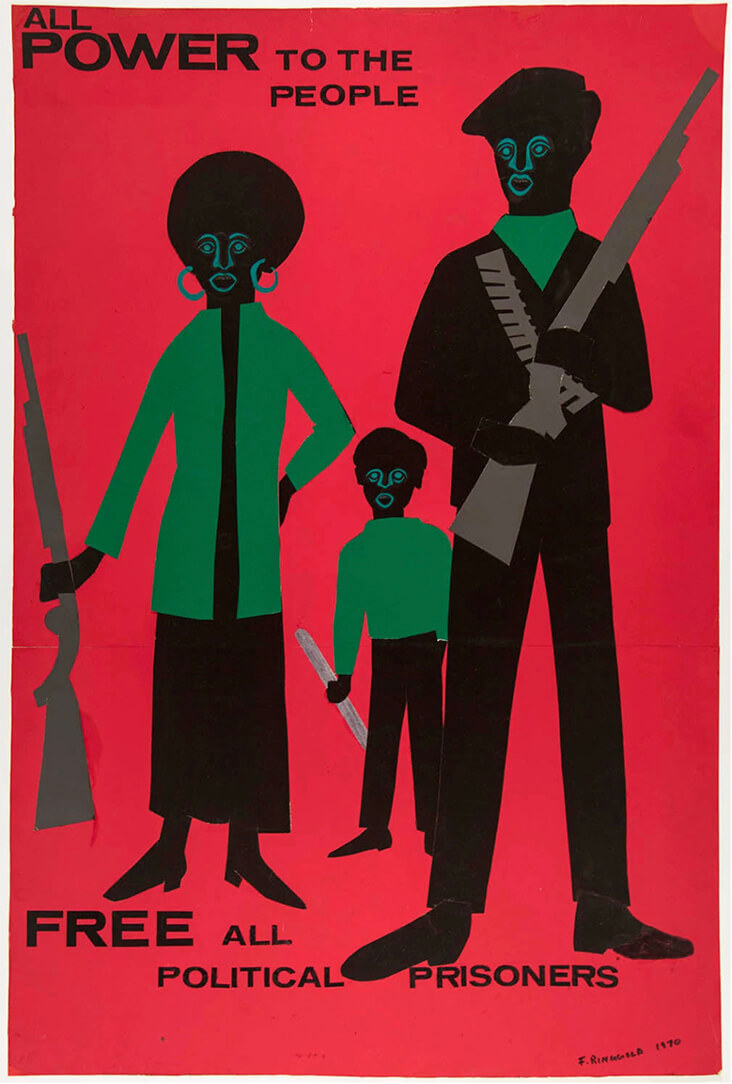

In the years that followed Ringgold made two breakthrough series’ of paintings, titled American People and Black Light which were directly linked to American politics, capturing black and white protagonists fighting against one another, sometimes in brutal, bloody battles. Throughout the following decades, Ringgold became an activist for feminist and anti-racist causes, staging prominent protests and founding groups including Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee, the Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, and the National Black Feminist Organisation. It was during this period that she moved into working with fabrics, creating masks and costumes that had a spiritual, African quality, exploring the vibrant colours, beading, and decoration of her heritage, while also creating anonymous, stereotyped guises which could be worn during staged protests.

Ringgold’s brutally honest series Slave Rape, 1983, opened up haunting material from the past, as terrified women attempt and struggle against their oppressors, amidst a supposed leafy, green paradise. Loose canvas squares are stitched onto quilted backdrops – this move gives the suffering these women endured a rightful place in the complicated tapestry of women’s history.

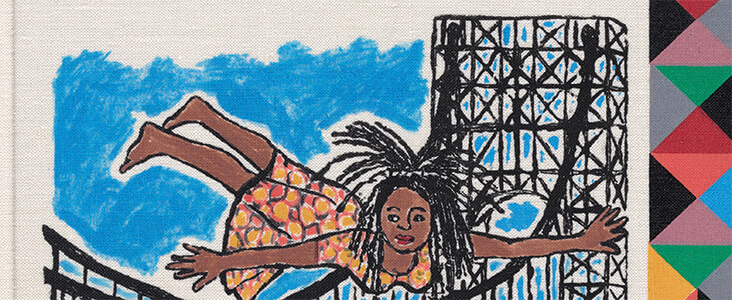

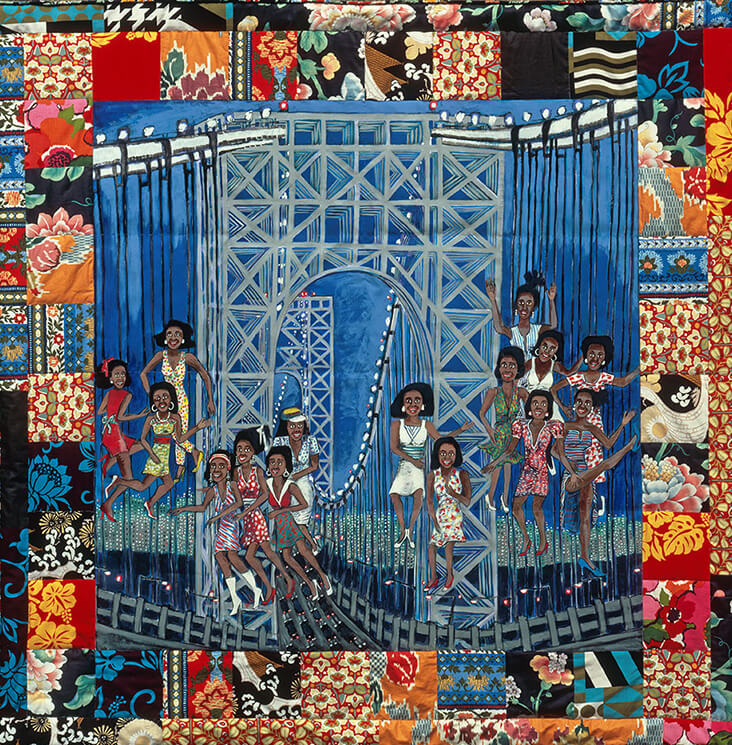

Ringgold worked alongside her mother in the years that followed, creating various quilted panels, and following her mother’s death in 1980, embraced quilting alone, drawing on its’ innate storytelling abilities, a practice she continues to develop today in her late 80s. In her most famous quilted artwork, Tar Beach, from the 1991 series Woman on a Bridge, Ringgold illustrates the life of a fictional, young African girl called Cassie Louise Lightfoot, surrounded by family and friends in an optimistic display of colour and life, a story which Ringgold later developed into a bestselling children’s book. In the distance, Cassie, and other women fly into the distance, unconstrained by prejudice or judgment. A symbol of American liberty, Ringgold writes Cassie’s simple, ultimate dream: “I am free to go wherever I want to for the rest of my life.”

7 Comments

Pingback:

A Word From Our Ancestors | Faith Ringgold - JarifullerPingback:

Make Mondays Happy - Elisha DasenbrockPingback:

400/450 Word Essays – Alexia Traill – Creative Dissent, Activism and ArtNancy Stockman

I always look forward to your articles and the connection Fabric-Store makes with art. Another wonderful and informative article!

Margie Cook

thank you for this wonderful article. as a quilter myself, i find her work amazing. love the color and design she uses to tell her story. her quilts , for me, bring out so many emotions. i can laugh and cry looking at the same piece. again i say thank you!

Carlin Sappenfield

Thank you for this interesting article and the beautiful quilts.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for all the comments – I agree her work is so emotive and powerful!