Woven with the Past: Quilts and Contemporary Art

“Quilts stimulate memories of warmth, security and home, yet their layers can also conceal hidden histories and untold stories.” Sue Prichard, Curator of Contemporary Textiles, the V&A, London

Quilts hold a special place in today’s culture, adorning the walls of museums and galleries as totemic mementos of the past. From abstract patterns to personal or political narratives, they vary hugely in design, but each holds hidden stories about comfort, survival, family, or community within its stitched layers. This interwoven relationship with our past is precisely why so many of today’s contemporary artists have adopted the practice of quilting, exploring how it can relate to their own lives or those of the people or cultures around them, illustrating stories of pain, suffering or peace with a uniquely hand-made quality. British artist Grayson Perry points out just how carefully interwoven the art of quilting is with our daily lives, observing: “We are born and we die and we make love under a quilt.”

A landmark moment for the recent history of quilting came in 2010, when London’s V&A Museum staged a huge showcase titled Quilts: 1700-2010, Hidden Histories, Untold Stories, dedicated to the art of quilting, curated by Sue Prichard, Curator of Contemporary Textiles. Displaying some of the finest examples in our history from the 1700s to the present day, the exhibition revealed a vast array of intricate, exquisitely made objects, each with their own unique story to tell. But perhaps most tellingly, the show concluded with a series of quilts by several of the world’s leading contemporary artists, showcasing just how fully integrated quilting now is within today’s visual culture.

Among those contemporary quilters included were British artists Grayson Perry, Tracey Emin and Natasha Kerr. Each of these artists in turn have adopted quilting practices to suit their own artistic voices. For Perry, art is a form of social commentary or political activism; his quilt Right to Life, 1998, was made via a computer programme, but the vivid complexity of the design resembled America’s history of crazy quilt patterning. Tying a part of America’s history with the contemporary debates around abortion rights, Perry’s subversive quilt collides history and present into one. An artist who has worked across a broad range of media, Perry notices how as quilt is “a traditional object that also looks like a painting, so it translates very well into the art gallery context…”

Emin’s quilts are more traditional, invoking both the feminine associations with careful hand-stitching and the quilt’s history as a site for embedding intimate, private languages. In To Meet my Past, 2002, an entire four poster bed is surrounded with quilted patches of fabric, each containing stories from her own painfully difficult childhood years. All Emin’s quilts are undoubtedly a labour of love, made with painstaking precision and filled with old fabrics loaded with memories, such as the old clothing of her friends and family.

Like Emin, Kerr’s quilted textiles are filled with poignant references to her past. In At the End of the Day, 2007, a family wartime photograph of her great grandmother and grandfather printed onto fabric is surrounded by a stitched together disjointed flag emblem. Reminiscent of the many patriotic quilts from throughout history featuring flags, including the great bicentennial quilts from the 1970s, hers is instead what she calls a “displacement flag”, on which she writes, “It was …not … a flag from any nation; it looked familiar, but wasn’t quite right.” Observing how this fragmented flag echoed the dislocated times of the image, she noticed, “I thought that given the context of the photograph it was quite fitting.”

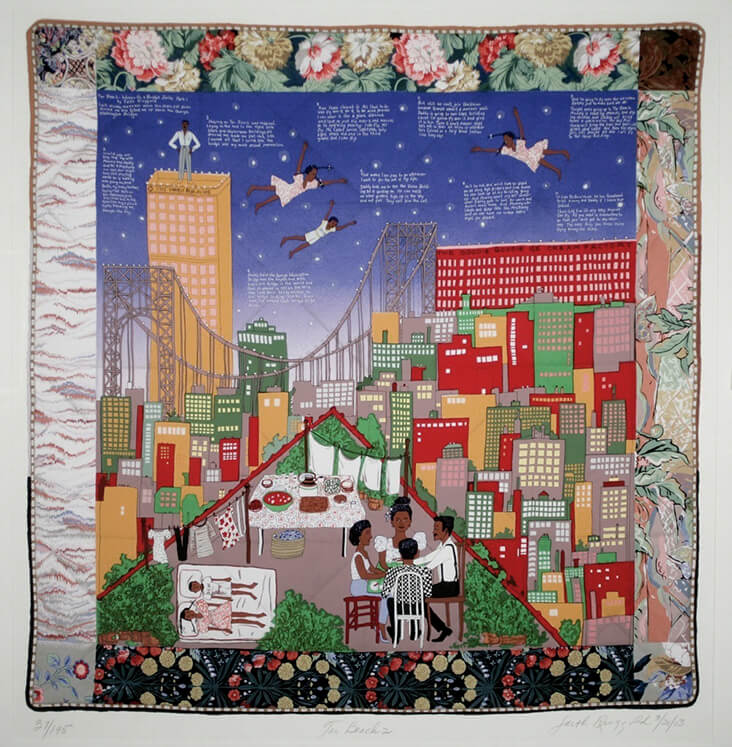

Since the 1970s quilting revival in America, quilting has also remained a vital strand of American culture. One of the most prominent and innovative quilting artists to emerge during this time was the award winning artist, writer and Civil Rights activist Faith Ringgold, who continues to produce stirring, evocative imagery that speaks volumes about the violence and persecution in African American history. Described by writer Arwa Mahdawi as “The quilts that made America quake,” Ringgold’s famous “story quilts” including Street Story Quilt, 1985 and Tar Beach, 1988 embrace a powerful, positive potential for social change. She chose quilting because it reflected the folk traditions of Black women, illustrating their struggles, private stories, and moments of celebration in a powerfully intimate language.

Another vitally important quilter to emerge from this era is the African-American artist Yvonne Wells, whose signature quilts illuminate events from the Civil Rights Movement that swirled around her as a child. As well as documenting some of the most harrowing moments of the era, including the bombing of the Church in Birmingham and George Wallace standing in the schoolhouse door to prevent integration in the University of Alabama, she also focusses on hopeful messages that suggest better times still to come, writing, “Everything I create is like a story, a record of history to benefit people in the future.”

One Comment

Vicki Lang

Quilts are a beautiful show of history of families and events alike. Thank you for a wonderful article of quilters from the past.