Stitching a New World: Quilting in the American Colonies

“The history of America can be seen in the history of quilts.” The National Monument of America

When pioneers set off for a new life in the United States, many carried with them the great tradition of quilting. Each family came to the New World armed with comforting quilts, some purely practical, others patched together with sentimental memories of family and friends left behind. In the centuries that followed quilting became a vital strand of these settlers’ lives, providing warmth, comfort and decoration, as well as bringing together communities, transforming a once strange and unfamiliar land into home.

Life was devastatingly hard in the early American colonies – settlers pulled together what little resources they had in order to survive. Homes were simple and food was scarce, but farms growing food, cotton and flax were eventually established, which provided resources to begin to build more comfortable lives. Fabric was expensive and hard to come by in America’s early communities, so quilting was largely reserved for the wealthy, but by 1840 when the textile industry expanded fabric was more widely available. Thrifty women cut apart and gathered together the little fabrics they could to produce stunningly detailed designs in a wide array of decorative motifs. In fact, the practice became so popular that quilting magazines were published, allowing makers to share their most resonant or visually striking designs.

The Nine Patch pattern was popular with pioneer women who had little fabric to spare. It involved cutting pieces into simple squares and combining them into a grid. Quick to sew, it was a popular design for utilitarian quilts covering beds and doorways, or even room dividers hung from the ceiling in one-bedroom homes. Girls on the prairie were taught this stitch from a very young age, learning from their mothers and grandmothers how to sew during daily ‘fireside training’ sessions.

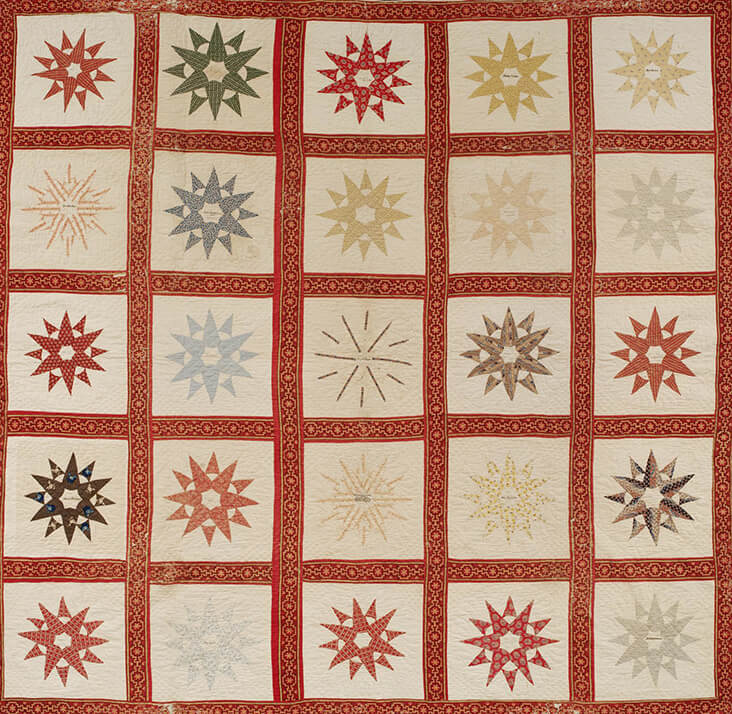

John Haldeman and Anna Reigart’s quilt from the American 19th century featuring a ‘sunburst’, or ‘rising sun’ pattern / from the V&A Collection, London

Other quilting motifs took on powerful symbolism and became a tool for political or artistic expression. These include the Log Cabin motif, which symbolised love, warmth and security with a red hearth square in the centre, surrounded by a series of stacked blocks. Almost any type of fabric could be used to make this heart-warming design, making it popular for those with leftover scraps from clothing and bedding. Light and dark schemes in this design were divided in the middle, symbolising the sun’s movement across the sky.

One of the most widespread motifs from this time is the Eight-Pointed Star, inspired by the star of Bethlehem, which represented their faith in God. This design was trickier to sew and came to represent the maker’s precise needlework skills, although some were so devotional that they deliberately sewed in a few imperfections to reflect our human fragility in the face of God’s power.

Before setting off to America, many women had friendship quilts made by groups of family and friends, which they took with them to start a new life. They provided a great source of familiarity and comfort in a strange and unusual new landscape. This tradition of family and friendship groups creating quilts to mark significant, life-changing moments was continued in the prairie – one particularly popular event that emerged in America was the quilt making ‘bee’, where women would group together their shared skills to produce a quilt in a single day for a bride to be. John Haldeman and Anna Reigart’s wedding quilt was made in 1846, featuring the ‘sunburst’ motif as a symbol of their burgeoning new life together.

The practice of quilting is also tied into America’s harrowing history of slavery; African workers were often hired to create quilts for their employers, but they also made quilts as a potent, patriotic form of self-expression when so many of their civil liberties had been taken away. African-American artist Faith Ringgold points out how quilting ” … was an art form that slaves used to keep themselves warm and to also import their art because they couldn’t bring the art forms they practiced in Africa. This was a way of them being able to continue their art in a way that was acceptable to the slavers because it was keeping them warm.”

One of the most powerful periods for American quilting also emerged during the Civil War. Women pulled together scraps of spare bedding or old clothing to make much needed utilitarian quilts that would keep soldiers alive through warmth. Some were made into a flag motif, while others contained messages of comfort stitched in or written in ink to offer comfort in the most harrowing of times. Symbolism was continued during the Underground Railroad, when it is said appliqued panels were hung outside certain safe houses to show slaves where to hide. Other women during the Civil War made finer quilts from luxurious pieces of fabric in wool, silk, and cotton, selling them at fundraising fairs to raise money for the war effort. Soldiers’ quilts were well used and few survive today, but many examples of fundraising quilts are held in museums around the world, representing the canny resourcefulness of women during these difficult times.

After the end of the war, the great quilter and artist Lucinda Ward Honstain made her world-renowned Reconciliation Quilt in 1867 as a symbol of the unity and patriotism of the Homestead Act. Honstain placed her own red-brick home in the centre of the quilt along with an American flag and a garden teeming with life, signaling the dawn of a new, hopeful era of unity.

One Comment

Vicki Lang

That you for the wonderful article and the beautiful old quilts. Quilts carry a rich history.