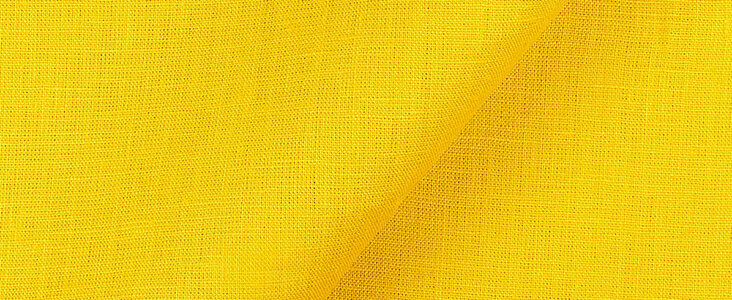

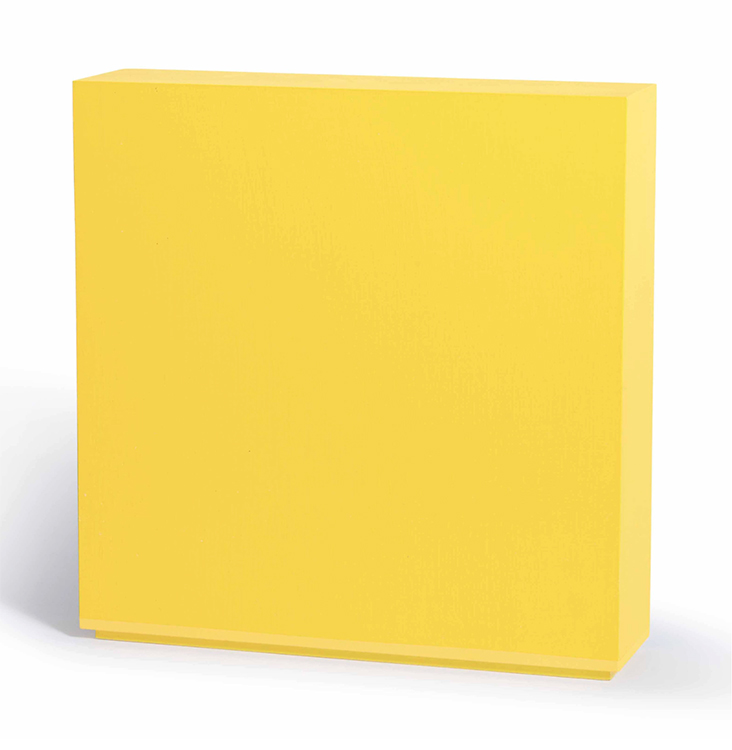

FS Colour Series: Sulphur inspired by Anne Truitt’s Golden Sunlight

The dazzling brilliance of SULPHUR Linen filled American artist Anne Truitt’s work with shafts of golden sunlight, encapsulating the glowing warmth of her native Washington. Truitt sought ways of infusing artworks with the colours of her idyllic childhood in Maryland, from dazzling white picket fences to blazing yellow sunlight and glistening stretches of juicy grass. A Minimalist at heart, Truitt translated these hues into subtly nuanced sheaths of colour, distilling memories of place into their purest and most refined essence. Reflecting back on her childhood she remembered, “in some mysterious way I felt myself to be colour.”

Born in coastal region of Easton in Maryland in 1921, Truitt’s childhood was wild, happy and free as she roamed the countryside soaking up fresh open space. Short sighted from a young age, Truitt’s vision became increasingly blurred, erasing superfluous detail in favour of hazy colour and light. Truitt saw this shift as a vital strand of her visual development, allowing her to sensitively observe the emotional resonances bound up in the wondrous realms of indistinct colour. In her late memoir she recalled, “I lived in a world composed of light and colour and shape…”

Sadly, Truitt’s contented childhood collapsed in the years that followed. The Great Depression pushed her parents into crippling debt, forcing them to move to Ashville in search of work. Truitt’s father descended into alcoholism while her mother’s health slowly deteriorated, marring Truitt’s adolescent years with uncertainty, and she longed for the carefree days of Easton. Sensitive and bright, Truitt was an outstanding student of Psychology at Bryn Mawr College, but she turned down the offer of a PhD at Yale in favour of working out in the field as a psychiatrist and nurse during the Second World War.

To escape from the stresses of war work Truitt read avidly, devouring books by Henry James, D.H. Lawrence and Dylan Thomas, who in turn inspired her to produce her own poems and short stories. But it was after completing a short course in sculpture that Truitt inadvertently found her true life’s calling as an artist – Truitt also met her future husband through a contact on the same course – after getting married the pair settled together in Washington. Truitt’s earliest sculptures were based on tall, upright figures, but after seeing artworks by the Colour Field painters Barnet Newman and Ad Reinhardt during a lifechanging visit to New York in 1961, Truitt made a dramatic shift into pure abstraction.

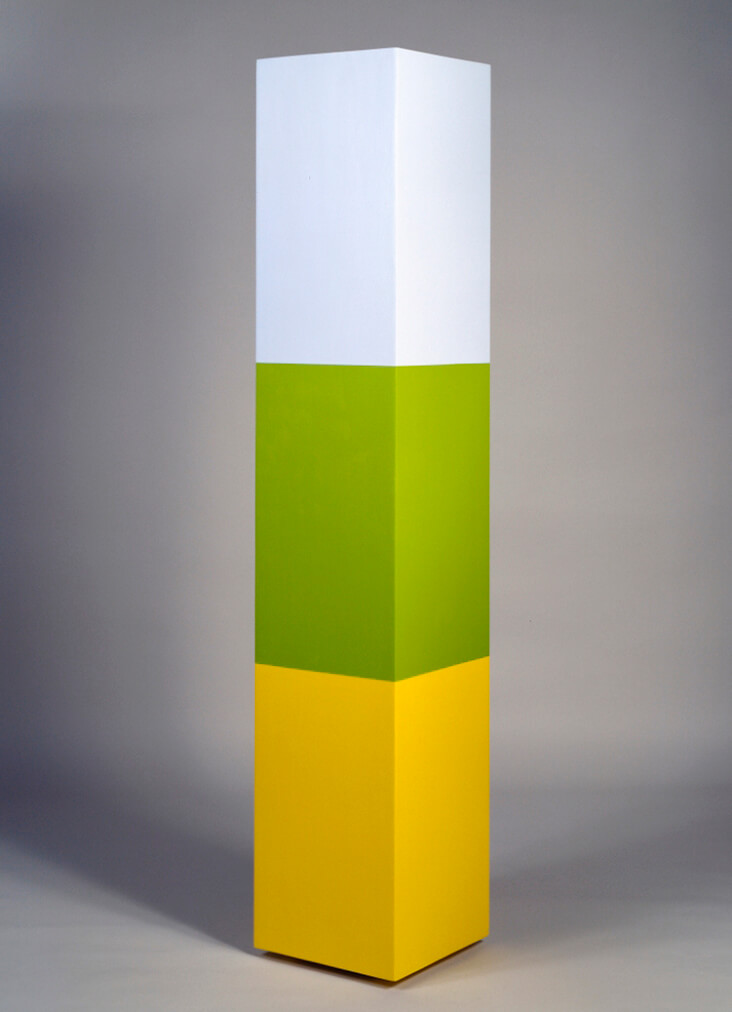

Truitt’s earliest abstract sculptures were tall and totemic, stacking blocks of unusual colour combinations together as if piled on top of one another, allowing them to hum and vibrate with sonorous musicality. Colours came from Truitt’s ‘inner eye’ as she increasingly looked back to the happiest and most settled period of her early life in Easton, finding her memories of the place gradually spilling out into her art. In A Wall for Apricots, 1968, three bands of colour harmonise into a glowing column of warmth and light, invoking the sensations of a glorious and carefree summer holiday. Sunshine yellow brings a deep radiating warmth into the arrangement, allowing the entire sculpture to glow with mellow tones of comforting familiarity.

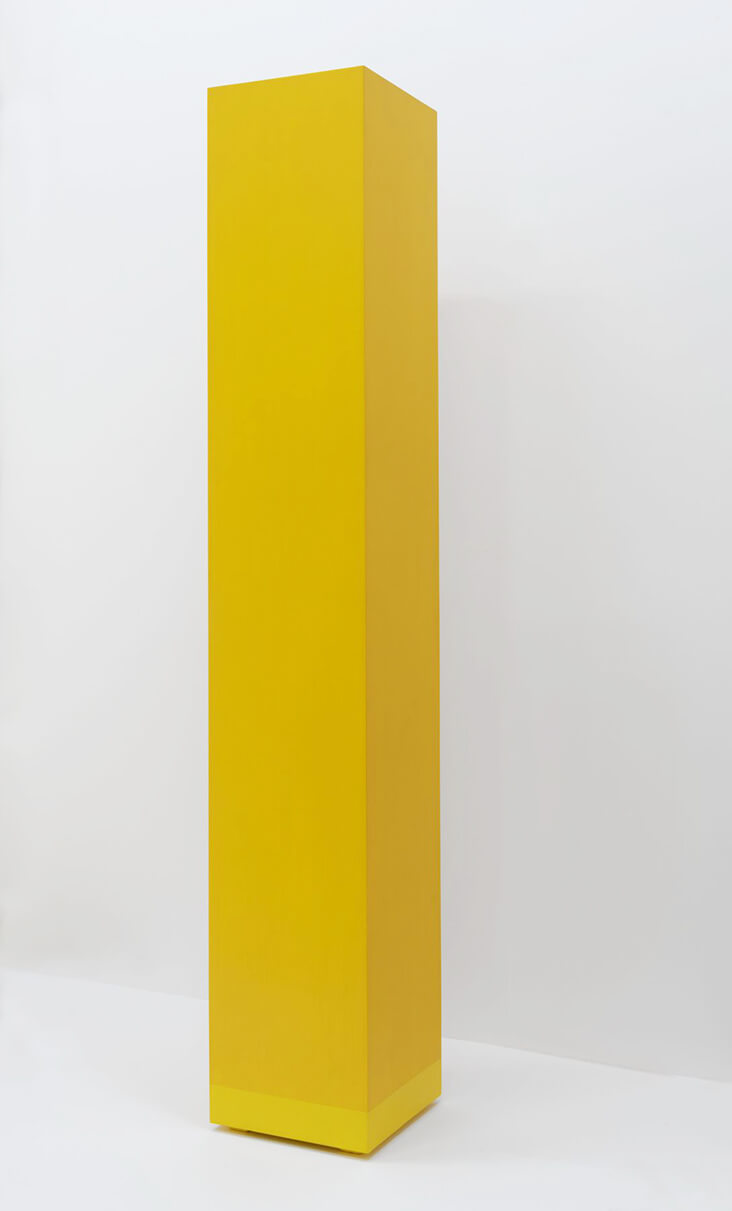

In 1964 Truitt travelled to Japan for three years with her husband, but it was not a happy time and her sculpture suffered as a result, leading her to destroy much of her work from this period. Following Truitt’s return to Washington she separated from her husband, taking their three children with her. The light, breezy air of her surroundings soon flooded back in to her practice, signalling a period of newfound hope and freedom. The monolithic sculpture Summer Child, 1973 zeroes in on a honeyed shade of golden yellow which forms a column of painted light, just tinged at the bottom with a lighter toned strip, a last gasp of sunlight slipping through a crack.

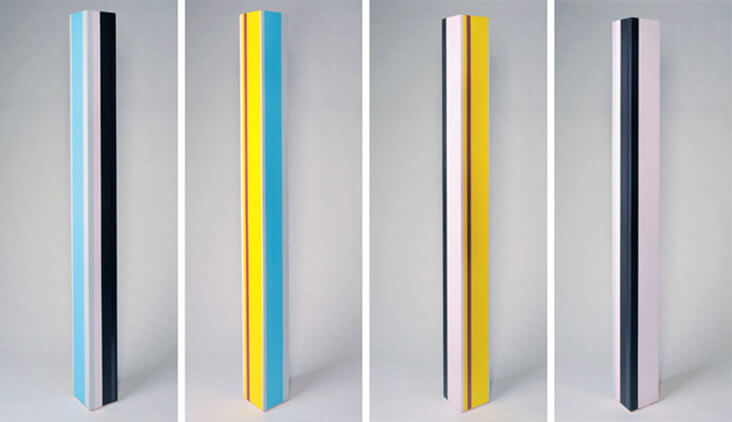

First Requiem, 1977 is even more slender, a quality emphasised by vertical stripes that adorn its sides, transforming a simple plank of wood into a weaving passage of flickering light. Two yellow stripes light up the sculpture with fiery brilliance, contrasting and complementing the shades around it. Truitt moved into wider, stockier forms in her later years, but she continued with the same language of refined, geometric abstraction, placing colour at the centre of her oeuvre. In Parva LIV, 2001, iridescent yellow is a wall of light, beaming forth with blazing sunlit radiance. An ever-so-slightly paler strip of yellow wraps itself around the base, as gentle and subtle as two bodies touching, invoking the intimate humanity at the heart of Truitt’s practice.

One Comment

Nancy Stockman

Thank you again. I love your articles and the connection to my garments to art