FS Colour: Malachite inspired by Kazimir Malevich’s Green Energy

MALACHITE Linen’s earthy, rustic green was a favourite with Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, investing his paintings with the lush, juicy vibrancy of fertile nature. A giant of 20th century art, Malevich made his name as the world’s first abstract artist, producing streamlined designs in bold shades of red, green, yellow and black, mimicking the colours of the landscape. He later turned figurative, painting ordinary people of Russia with great pathos, yet he held on to the same solid forms and rustic colours of his abstract art, allowing the same active, breathing energy to flow through them. Reflecting on the power and autonomy of his canvases, he wrote, “A painted surface is a real, living form.”

Malevich was born in Ukraine to Polish parents and became the eldest of fourteen siblings. Jobs were scarce and his parents had to move frequently around the Russian Empire in search of employment. They eventually settled in the villages of Ukraine, where Malevich spent much of his childhood living amongst the wild tangles of sugar-beet plantations. The little art he had access to was Russian folk art and embroidery, whose simplified forms and dazzling shades of red and green had a profound impact on him; from the age of 12 he began making his own drawings, emulating the folk art style.

From 1895 to 1896 Malevich studied drawing in Kiev and in 1904 he moved on to study fine art at Moscow’s School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. In Moscow he moved through various styles including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism and Art Nouveau. But in 1907 he befriended an avant-garde group including Wassily Kandinsky and Mikhail Larionov, who were experimenting with the geometric, abstracted styles of Primitivism, Cubism and Futurism, with faceted, geometric panels of pure, bright colour.

Malevich’s early career paintings captured scenes of Russian peasant life as influenced by the Russian folk art and rural surroundings of his childhood. But as the painting Landscape, 1911, reveals, he fused these interests with the expressive, abstracted language of Cubism. Here fervent, earthy green leaves seem to rustle and splinter apart in the shimmering breeze, surrounding rustic houses blushed pink by smatterings of evening sunlight.

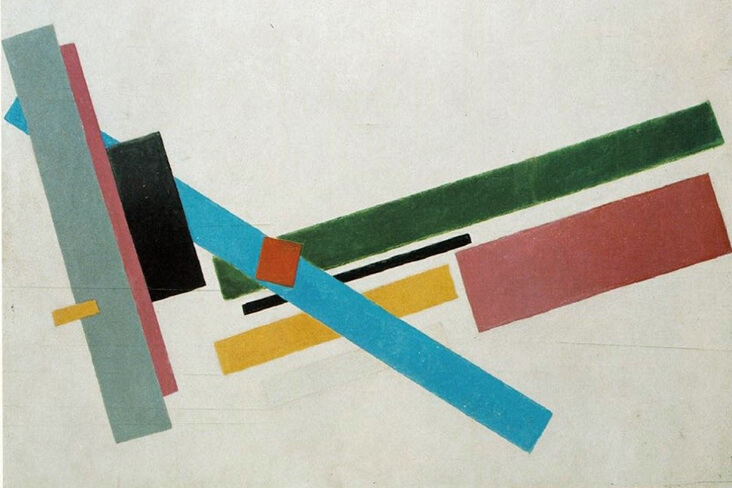

By 1915 Malevich had abandoned reality completely in favour of his own pure, geometric abstraction, which he labelled Suprematism. Heralding this one-man movement as the liberation of art from the shackles of representation, he declared in his manifesto, “I have beaten the lining of the coloured sky, torn it away and in the sack that formed itself, I have put colour and knotted it. Swim! The free white sea, infinity, lies before you.”

Paintings typifying this new, abstract style include Suprematism, 1915 and Suprematist Construction, 1916, each portraying floating forms hovering like celestial creatures through infinite white space. In the former, colours jam together in a huddled group, while the latter is split apart as if falling through space, allowing dynamic shapes to intersect and cross over one another. In both, a patch of rich, earthy warm green brings depth and life to an otherwise cold colour arrangement, making each glow with the freshness of new green grass.

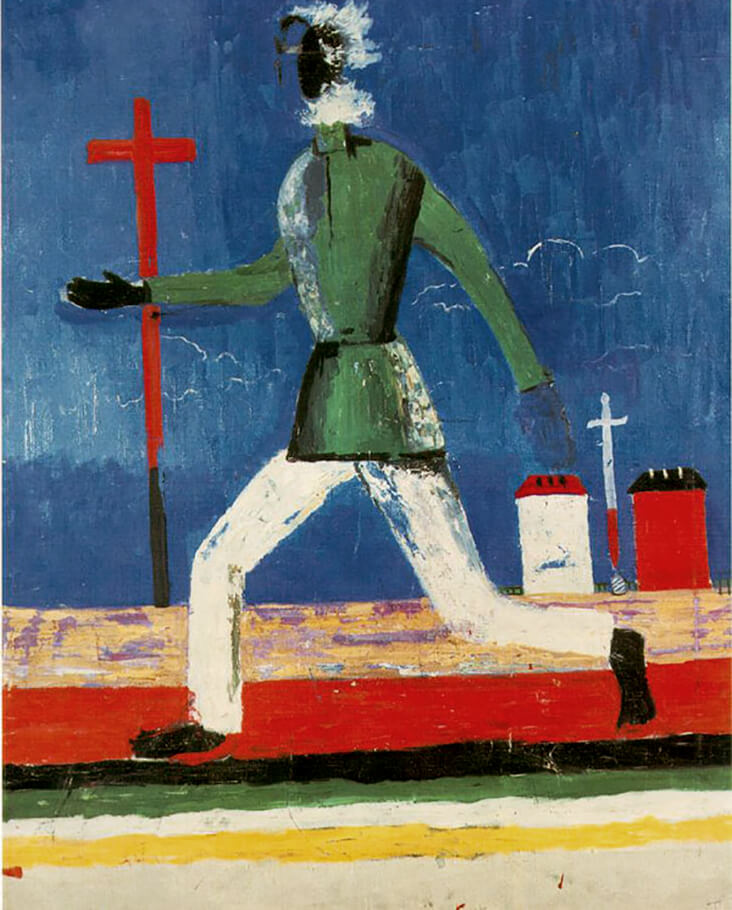

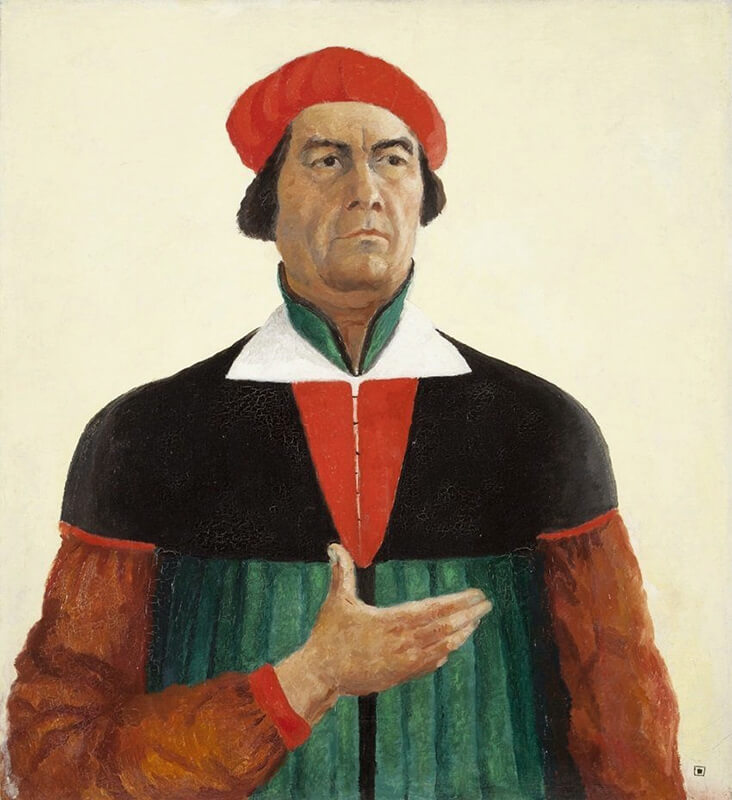

When state sponsored Socialist Realism took over Russia in the 1920s, abstraction was forbidden and Malevich was distraught. Determined to keep painting, his later art turned figurative, but he surreptitiously retained elements of the abstraction he loved, holding on to slabs and panels of bright, simplified colours to capture the world around him. In the striking Self Portrait, 1933, Malevich stages himself as a modern-day Albrecht Durer in traditional Renaissance costume, while dazzling red is tempered by strands of evergreen that seems to expand across his chest, sprouting leaves out of his crisp, stiff white collar like creative energy trying to break free. In the later Running Man, 1934, sharp streaks of colour run as free as the central figure, whose gathering pace lifts him free from the ground below. Wavering strands of bottle green run across the horizon and the enlivened man’s clothing, as energised as life itself, a message of continuity and hope, even amidst the most challenging and oppressive of times.

Leave a comment