Lorna Simpson: The Great Unknown

“In terms of making art, and writing, and anything that we do as artists where we have to step up to the plate, it should be uncomfortable, it should be nerve wracking, and there should be this level of the unknown.”

Fearless is a word often used to describe Lorna Simpson: like an intrepid explorer trekking into the wilderness, her chameleonic practice as an artist is bold and risky, shifting from photography and collage to film, performance and painting. Bringing together such wildly divergent styles and mediums is an overarching concern with her identity as an African-American woman living in contemporary America, and the weight of history and memory that continues to lurk in the shadows and corners, infiltrating so much of ordinary life.

New York Artist Lorna Simpson Photographed for The Edit “The Interview” / Photo by Bjorn Iooss / 2013

Simpson was an only child, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Jamaican-Cuban father and an African-American mother. Cultured and intellectual, Simpson’s parents had already moved from Midwest America to New York to be more immersed in the cultural scene, one which they were keen to integrate their daughter into as she was growing up. “My artistic interests have everything to do with the fact that they took me everywhere,” remembers Simpson.

Childhood memories and family experiences would come to inform her artistic practice as an adult, from overheard stories and torn out magazine advertisements to the jazz music of John Coltrane and Miles Davis. As a young child Simpson took dance lessons, and in one poignant experience when she was around 10 or 11, she vividly remembered performing on stage at the Lincoln Centre, where she wore a gold bodysuit and matching shoes. Though she struggled through the performance, it was a steep learning curve, one that she says taught her she was better prepared to be a spectator than a performer, a moment of awakening later captured in the performance work Momentum in 2010.

Simpson’s creative training began as a teenager with a series of short art courses at the Art Institute of Chicago, where her grandmother lived, followed by attendance at New York’s High School of Art Design. Moving on to a degree at New York’s School of Visual Arts, Simpson first signed up for painting, but she later shifted to photography, realizing, as she put it, “everybody (else) was so much better (at painting). I felt like, Oh God, I’m just slaving away at this.” In photography she found a more direct way of engaging with real life around her, which she says, “opened up a dialogue with the world.”

While still a student, Simpson took on an internship at the Studio Museum in Harlem, an experience which allowed her to expand her practice in new ways, as she recalled, “I found myself in all these amazing situations that opened my eyes to the practice of contemporary art.” It was here that she first met the artist David Hammons, who was there on a residency, and his fluid, open-ended practice came to have a profound influence on her ways of working, while also encountering the work of fellow Black artists in Charles Abramson and Adrian Piper.

New York Artist Lorna Simpson Photographed for The Edit “The Interview” / Photo by Bjorn Iooss / 2013

Travel during her student years through Europe and across North Africa allowed Simpson to experiment with documentary photography as influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Roy DeCarava; she spent months producing hundreds of photographs of street life as she moved from one location to another. But by the time she graduated, Simpson already felt she had exhausted her take on the documentary style. Moving into the field of graphic design to find steady employment, Simpson took on work for a travel company, all the while continuing to frequent the New York underground art scene, searching for a way to express what was going on around her; the era was a period of struggle and hardship for African- Americans when the civil right movement had passed, but Black Power was failing, as poverty, unemployment and racist attitudes still ran deep.

Fortuitously, Simpson met the African-American artist Carrie Mae Weems at an event in New York; at the time Weems was still a post-graduate student at the University of California, and she persuaded Simpson to move to California. “It was a rainy, icy New York evening,” remembers Simpson, “and that sounded really good to me.”

On the MFA course at University of California, Simpson found conceptual art was the leading style, and it was here that she discovered her signature voice, exploring the ways visual material could address the lives of African-American people and the prejudices they were facing. In her earliest series’, Simpson combined her own staged photographic imagery, taken from models in a studio, with panels or excerpts of text, which she found could open up the images for wider interpretation. Such texts were based on snippets of conversations she had overheard, or from the news, giving them a pertinent, socially aware slant. Even so, her tutors weren’t convinced – Simpson remembered them being somewhat dumbfounded by her work and even wondered if she might not graduate.

Back in New York, Simpson found a much warmer reception; here, her voice and message were ready to be heard. Like Simpson, various multi-cultural artists within the city were beginning to explore attitudes towards their identities. “If you are not Native American and your people haven’t been here for centuries before the settlement of America, then those experiences have to be regarded as valuable, and we have to acknowledge each other. This is the premise by which I view the world,” wrote Simpson.

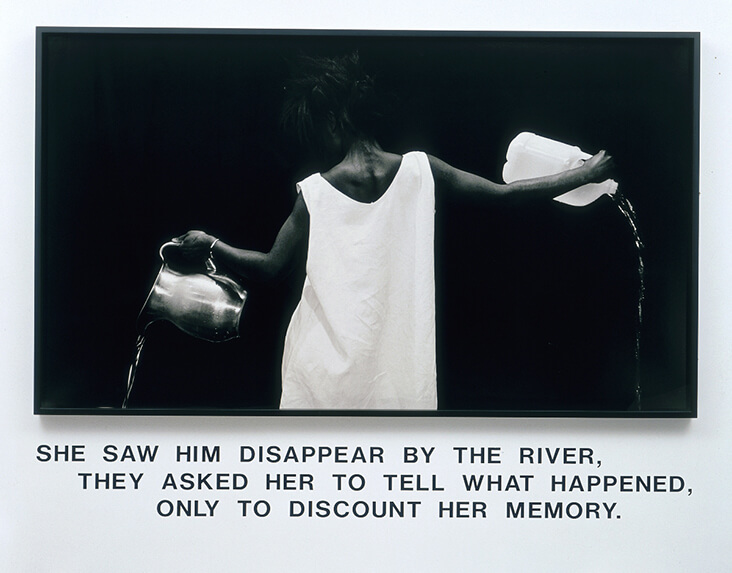

By the late 1980s galleries were clamouring to show Simpson’s work; “I had a career because of it,” she recalled. In some of her most prominent works of this period Simpson spliced imagery of African-American women with painfully direct commentaries, opening up viewer’s eyes to the discrimination still prevalent all around them; The Water Bearer, 1986, one of her most publicised works of art, illustrates a woman from behind pouring water from two separate containers. The detached, backward few of her protagonist is a stark reminder of the dehumanising effects of racism. Below her is the inscription, “She saw him disappear by the river. They asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.” The oblique statement is deliberately obscure, only giving away enough information to hint at inherent sexism and racism, and how easily a person’s outward appearance can impact the ways they are perceived or believed. Simpson observes how easily in society, “… what one wants to voice in terms of memory doesn’t always get acknowledged.”

In C-Rations, 1991, the text “not good enough” and “but good enough to serve” accompanies another model, while Untitled (Two Necklines), 1989, brings in a series of chilling, harrowing words in relation to the black woman’s body, including “areola” for breastfeeding or sex, “noose” in reference to lynching and the haunting horror of the victim’s experience is captured with the words “feel the ground sliding from under you.”

Simpson’s career was in full swing by the 1990s, during which time she became one of the first African- American women to be included in the Venice Biennale. During this decade she met and married the artist James Casebere and they had a daughter, named Zora. Though it wasn’t always easy, Simpson continued to make work while caring for a new-born – she even remembers taking her two-month-old baby with her to Japan to complete a residency.

During this time, while sorting through her grandmother’s old copies of Ebony and Jet magazine, vintage periodicals aimed at the African- American community that were prevalent in the 1950s, Simpson found a wealth of visual material relating to feminine identity and prescribed ideals. It was the advertisements that paired black women with white attributes, including straightened hair and whitened skin that caught her eye. In the lithograph series Wigs, 1994, Simpson highlights the political implications of African- American hairstyles, bringing together various hairstyles from short, curly afros to long, blonde hair, while excerpts of text relating to the women and entertainers who have used wigs as a form of expression, concealment or disguise. Laid out in a group, they take on curious, biomorphic qualities, lending them a mysterious life-force beyond their wearer.

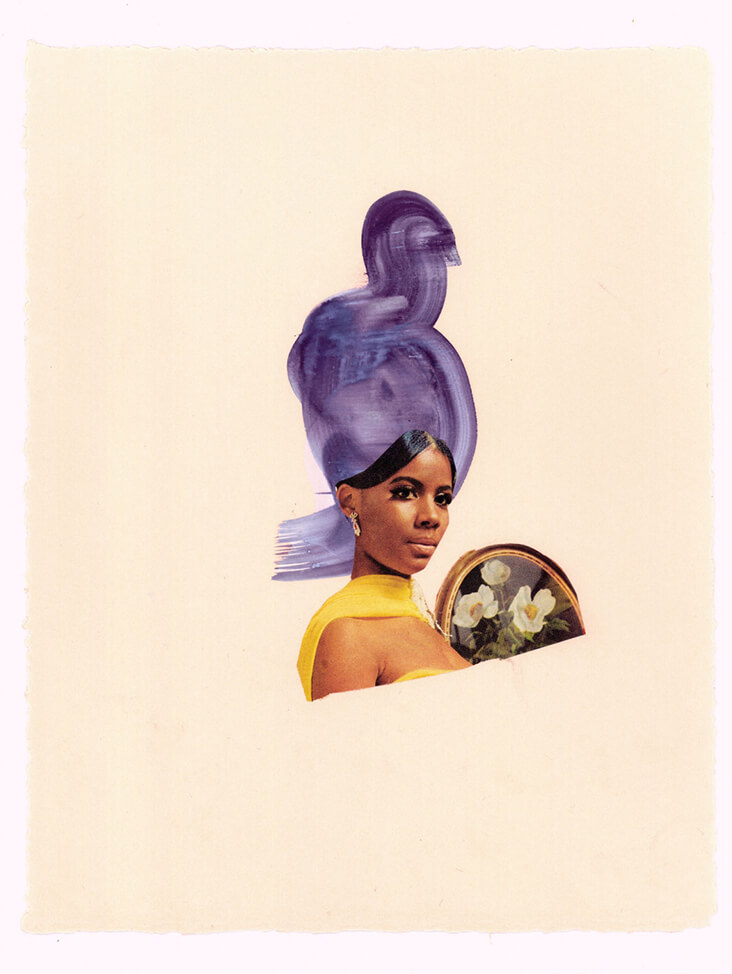

Between 2011 and 2017, Simpson revisited this material, transforming women lifted from Ebony magazine with expressive swathes of watercolour painted, candy coloured hair, reminding us these women are not, and never were real, but part of an unknowable realm of fantasy. Poet Elizabeth Alexander also sees Simpson’s treatment to these women as a form of liberation, and a chance to rewrite their history, commenting, “…black women’s heads of hair are galaxies unto themselves, solar systems, moonscapes, volcanic interiors… Watercolour is the perfect medium for Simpson here because of how it holds light and appears to be translucent. But it is also a wash, a shadow cast over what we cannot know in these women.”

Other mediums including film and performance have allowed Simpson to further investigate her experiences of the world. In Corridor, 2003, a two-part film, one half sees a Black woman acting out the role of a household servant from the 1860s, while in the other, the same character walks through a 1960s suburban home, now the master of her own space, but still rippling with echoes of the past. Video art has also allowed Simpson to tap into the richly evocative, sometimes painfully emotional potential of music, a carrier of memory, as seen in Cloudscape, 2004, in which an African-American man whistles an unidentified folk song, perhaps from Simpson’s childhood, as he fades into the blinding fog of the past.

New York Artist Lorna Simpson Photographed for The Edit “The Interview” / Photo by Bjorn Iooss / 2013

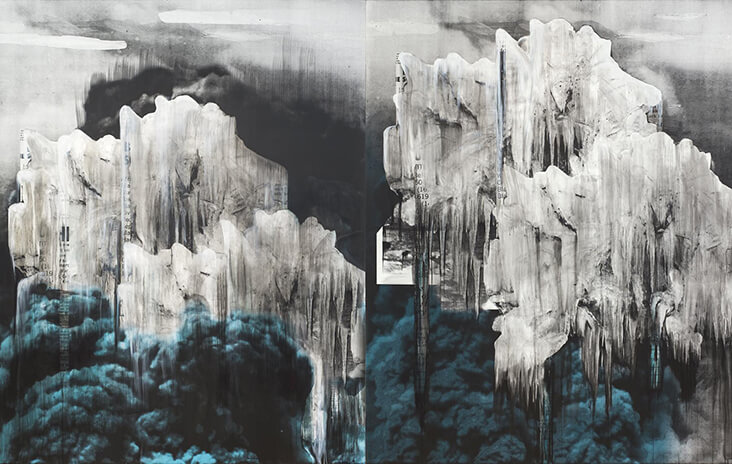

In a recent departure, Simpson has branched out into painting, an entirely new territory for her which was not without its risks. “At first I was a little intimidated about working in this way,” she commented, adding, “It seemed a little absurd … and then I thought … you fail, you fail. So what?” In many of her most recent paintings icebergs and epic mountains expand across vast, engulfing canvases. They might seem like a radical shift from her usual, socio-political practice, but Simpson insists they follow the same school of thought – she likens these icy, inhospitable terrains to the current culture in America, which is still rife with racism, discrimination and segregation, observing, “American politics have, in my opinion, reverted back to a caste that none of us want to return to…”

Much like her contemporaries, including Kara Walker, Glenn Ligon and Ellen Gallagher, Simpson’s art continues to push boundaries and subvert ingrained attitudes towards race and gender. But it is the experimental, enigmatic strand of reinvention that truly defines her as a modern master, one who has remained steadfastly true to her own inner voice, as she writes, “I’ve always done exactly what I wanted to do, regardless of what was out there. I just stuck to that principle and I’m a much happier person as a result.”

Feature image: Wigs / Lorna Simpson / 1994

Leave a comment