The Colourful Poetry of Yinka Shonibare

“In a lot of my work it’s important that there is this ambiguity, that it doesn’t answer these questions and that there are no definite statements being made. So it’s more a type of poetry; it’s a poetic statement.”

Yinka Shonibare’s art is a balance of opposites, combining irreverent, playful fantasy with the shocking brutality of nightmares. The in-between worlds he creates, where people sprout wings, grow animal heads, teeter under piles of cakes or shoot themselves and each other, reflects the dark complexities of post-colonial identity. A British man of African descent, Shonibare found fabric a potent carrier of his ancestral past, particularly the ‘African’ batik fabric that colours most of his practice, and shares a past as complex as his own. He writes, “My work addresses the idea of having this fusion or hybrid cultural identity and what that produces.”

Born in London to wealthy Nigerian parents in 1962, Shonibare’s family moved to Nigeria when he was three, and he remained there until he was 16. He grew up in Lagos, but his family continued to return to England in the Summers, investing in him a long-term connection there. He remembers, “I always visited London regularly, and it has never felt like an alien place … it has always felt like a home from home.” When he was 17, he moved to London to study his A-Levels, but he was struck with transverse myelitis aged 18, leaving half his body permanently paralyzed.

With determination he moved on to study fine art at Central Saint Martins College of Art in London, then Goldsmiths at the University of London, emerging as one of the Young British Artists in the 1990s. Since then, his practice has continued to explore the relationship between Africa and Europe, through a language that unites political and cultural references from both histories.

One constant strand throughout his practice has been the use of Dutch wax ‘African’ fabric, a brightly coloured, floral print that has deep significance for Shonibare. On the one hand, he makes use of the work for its distinctive ‘African-ness’, a highly distinctive fabric that instantly brings to mind African societies. But he is also attracted to the fabric for its complex, multi-cultural history; it was first mass-produced in Holland, as inspired by Indonesian Batik designs, and then sold on to West Africa in the 19th century from Europe. The Afro-European history gives the fabric a complexity which Shonibare relates to his own identity, as both British and African, highlighting how cultural signifiers are never as straightforward as they might seem. Shonibare writes, “I’m very interested in the colonial relationships between Africa and Europe, and the fabrics have become a metaphor for that.”

The fabric is brought to life in Little Rich Girls, 2010, where batik fabrics are beautifully transformed into a series of upper-class Victorian dresses and suspended from the wall like museum artefacts. In other works, such as Ibeji (twins) Riding a Butterfly, 2015, his sumptuous, richly decorated fabrics are brought to life as full-bodied characters, with globes for heads as a reference to their multi-racial identities. Taxidermy is also combined with fabrics, as seen in the golden gun-wielding Revolution Kid (Fox Girl), 2012, part of a wider ‘Revolution Kid’ series, which makes reference to the violence and racial tensions of the 2011 London Riots.

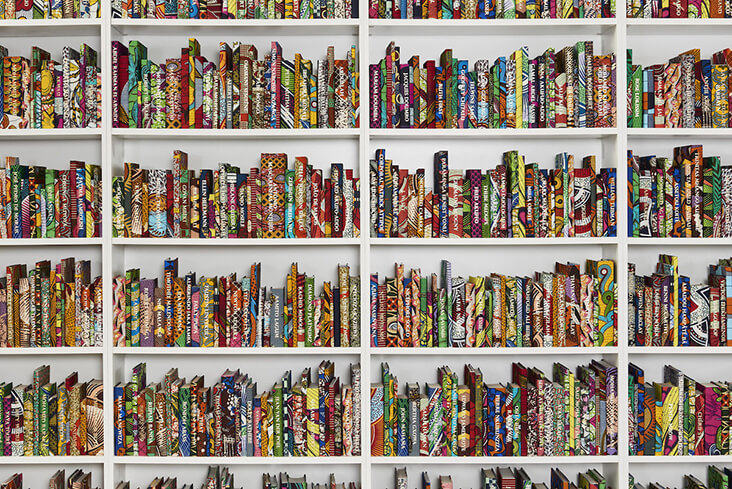

In the immaculately dressed ‘Butterfly Kid’ series, including Butterfly Kid (Girl) IV, 2017, Shonibare addresses the wider concerns of global warming and the ‘butterfly effect’, with young children sprouting wings as if ready to launch into a new life on another planet. One of his most recent and striking The American Library (Activists), 2018, Shonibare made batik covers for six thousand books, while the spines bear the names of first- or second-generation American writers with an activist slant, some extremist, others liberal. A vibrant and enticing celebration of literature and diversity, Shonibare’s fabric library highlights the vital importance in freedom of speech and its role in defining the complexities of identity.

5 Comments

Nayila Wright

He is such a vibrant artist and I feel fortunate to have viewed some of his work in person a few years ago while displayed at the Brooklyn Museum. As someone who comes from a mixed background with my own roots in West Africa and Europe, his work resonates with me. I appreciate how you touched on the complexity of the relationship of wax fabric and it’s connection to Europe. Beautiful article!

Pat Meyers

His work is so energetic and beautiful, and intriguing. Your articles always inspire me to research the artist. Thank you for stretching our art knowledge and pointing out the connection of art and sewing, color, form – all of it. Don’t stop!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the positive feedback!

Vicki Lang

What a marvelously colorful artist. His works are very eye catching with the complex riot of color.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the comment – yes indeed, his colours are so full of vibrancy and life!