Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Freedom with Fabric

“The work of art is a scream of freedom.”

The astonishing, monumental ambition of husband and wife duo Christo and Jeanne Claude was limitless, covering vast swathes of land, sea and architecture. Merging textiles with land art, they transformed some of the world’s most famous sites, draping, wrapping and adorning them with specially engineered, vivid fabric, producing non-invasive, temporary interventions. Not just sensationalist and attention grabbing, their art aimed to draw our attention to the innate, abstract and sculptural qualities of scale, volume and energy, qualities that might otherwise go unnoticed. Art critic William Cook writes, “…like all great art, (their) work does something… that stays with you. (Their) artworks make you see the world around you in a slightly different way… The world becomes more beautiful than before.”

Both Christo Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude de Guillebon were both born on the same day – June 13, 1935 – which they came to see as part of their unique bond. Christo hailed from Gabrovo in Bulgaria, while Jeanne-Claude was born in Casablanca, Morocco. The pair met in Paris, where both were working as artists, and married in 1959. Though they began working together collaboratively in the early 1960s, their joint artworks were often attributed to Christo alone – it was some time before Jeanne-Claude’s role as equal partner was widely recognised. In early artworks, their simple, trademark process of wrapping was applied to ordinary objects including supermarket trollies, paintings and oil barrels, as seen in Dockside Packages, 1961. The act of wrapping and disguising familiar objects with tarpaulin fabric and rope could create a new, strange unknown, a process the art critic David Bourdon described as “revelation through concealment.”

In the mid-1960s the couple moved to New York City, where they integrated themselves with the Arte Povera movement, which focussed on experiments with every day, humble materials. But by the end of the decade the two were branching out into more ambitious ideas, influenced by the rising trend for Land Art. In Wrapped Coast, 1968-9, the artists covered a long stretch of rocky coastline in Little Bay, Sydney, Australia with over 1 million square feet of a specially designed, hardwearing fabric – securely attached to the cliffs with rope, studs and fasteners, it remained in situ for 10 weeks before being carefully removed.

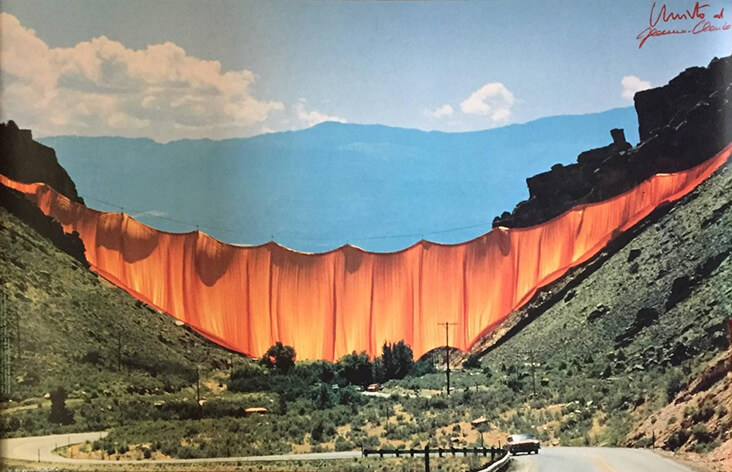

In 1970, Christo and Jeanne-Claude began preparations for The Valley Curtain, a site-specific artwork in Colorado Valley. But as with many of their projects, the deceptive simplicity of the final work took years of drawing, model-making and fundraising to complete. The plan was to stretch and tie an orange crescent of nylon fabric across a valley, filling a space over 1,250 feet wide and 365 feet high. But in the first attempt the fabric ripped and blew away. In the second attempt, in 1972, the fabric remained in place for 28 hours, just long enough for it to be immortalised in a series of striking photographs before coming untied.

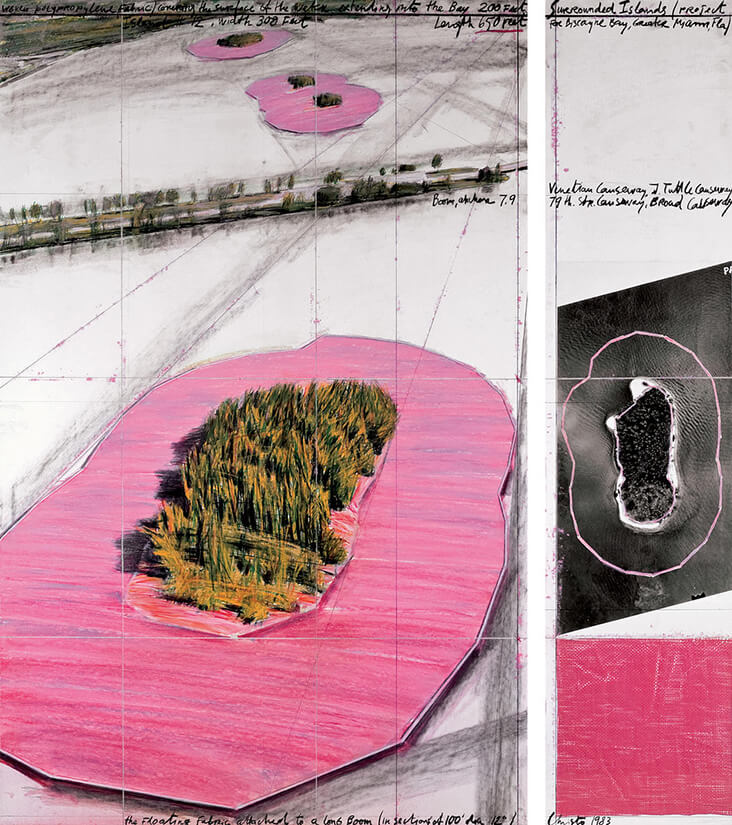

Moving on to ever more daring locations, Christo wrote, “We never do the same thing again … Each time is a new adventure, a new journey – it’s like an expedition.” In Surrounded Islands, 1983, dayglo, shiny pink fabric formed iridescent halos around a group of islands in Biscayne Bay, near Miami. Made from waterproof polypropylene, floating fabric hovered on the water’s surface, sewed into 79 patterns to follow the outlines of 11 different islands.

The Umbrellas 1984-91 took two concurrent forms in Japan and the United States, drawing comparisons between the two countries. In Ibaraki, Japan, a field of electric blue umbrellas reflected the country’s proliferation of watery rice fields, while in the wilderness of California, an array of yellow umbrellas echoed sun-bleached fields of dry land.

Perhaps their most famous and celebrated wrap was Wrapped Reichstag, 1971-95, an enormous project that took over 24 years to complete as they fought for permission and funding. The end result, a transformative, shimmering sheath of pleated white fabric covering the entirety of Berlin’s monolithic Reichstag building, made them household names.

Jeanne-Claude sadly passed away in 2009, but Christo has continued alone; in the recent installation at Lake Iseo, Italy, The Floating Piers, 2014-16, 100,000 square metres of yellow fabric on floating, modular cubes formed a strikingly bright walkway linking the island with mainland Italy. Like all his projects, Christo intended this work to be temporary, carefully making sure the remnants could be recycled, something made all the more possible by choosing fabric, rather than more permanent or solid materials. On the liberation gained through this ephemerality, he writes, “The disappearance of the artworks is a part of the aesthetic concept. That makes them deeply rooted in freedom.”

Leave a comment