Azzedine Alaia: Following Female Forms

“My obsession is to make women beautiful. When you create with that in mind, things can’t go out of fashion.”

Famously private and mysterious, Tunisian-born, Parisian designer Azzedine Alaia remains one of the fashion world’s most enigmatic figures, one who rebelled against the structures and conventions of the industry to follow his own path. Known today as the “King of Cling,” he made his name in the 1980s for his form fitting, body-con and fit and flare dresses that hugged the sculptural, curved contours of the female body, accentuating the wearer’s natural femininity. Rejecting notions of fast, seasonal fashion and trends that come and go, he worked at his own pace, slowly producing timeless, elegant designs that are as endlessly flattering and popular today as they were nearly four decades ago, when he first made his name. “I make clothes,” he observed, while “women make fashion.”

Alaia’s upbringing in Tunisia was a far cry from his later years in Parisian haute couture; born to Tunisian wheat farmers, he, his twin sister and their younger brother lived out the summer months amidst dusty, wide-open fields. They were sent to live with their grandparents in Tunis and the seaside town of Sidi Bou Said during colder seasons, where Alaia experienced his first taste of glamour through his sophisticated grandmother, aunts and family friends. In particular, the family midwife, Madame Pinot, nurtured the young Alaia’s fascination with the arts, letting him pore over her archive of Vogue magazines, fashion catalogues and art books. “She gave me my first book of Picasso,” he later remembered.

It was Madame Pinot who encouraged Alaia to go to art school, at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Tunis, although the move was, as Alaia recalled, “against my father’s will.” Undeterred, his fascination with form initially drove him to study sculpture, while surprisingly, his twin sister was the one who took on fashion design. Searching for work to supplement his studies, Alaia persuaded his sister to teach him how to sew, skills he put into action with a job at a local dressmaker. “The owner was looking for someone to finish up the dresses,” he remembered, adding, “My sister had learned sewing … and she had a notebook with all the basics. That was my first real experience with fashion…”

Local customers put Alaia in touch with a dressmaker who made replica Balmain clothing, which in turn led him to secure a position working for Dior in Paris in 1957, a role which fell through after only five days as he did not have, as he said, “his papers in order.” Stranded in Paris and in desperate need of employment, Alaia found an unlikely live-in job as a seamstress and babysitter for the Comtesse Nicole de Blegiers and her large, aristocratic family. Through the Blegiers family’s wide circle of Parisian connections Alaia soon found a series of private clients to make clothing for, including the writer Louise de Vilmorin, the actress Arletty and the Rothchild banking family. As his reputation grew, so too did his list of customers; such was the quality of his work that by 1979 he had earned enough prowess to open his own fashion house in 1979.

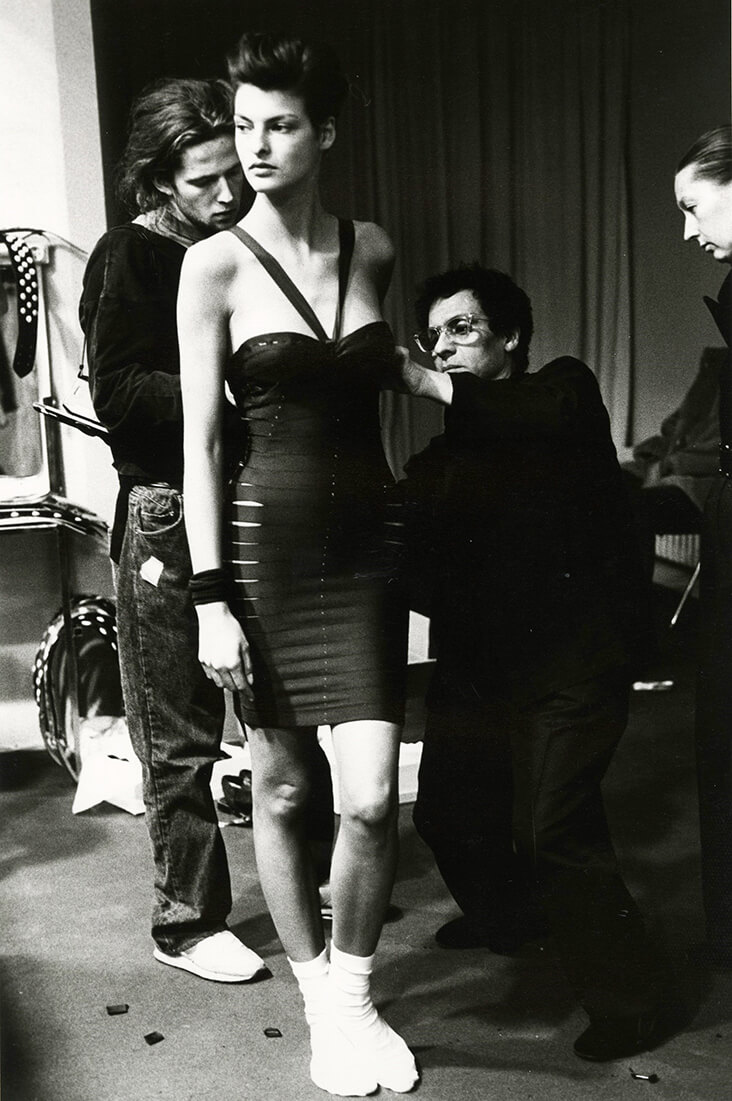

Launching his first ready-to-wear collection in 1980, Alaia revealed designs that would herald his nickname as the “King of Cling” including form fitting leather, belted coats and knitted garments that hugged bodily contours. Decoration was woven into the internal structure of his garments, as seen in his zipper dress famously worn by Arletty, in which a zip neatly coils like a curl of smoke around the body, or fine, viscose jersey intricately woven into ribbon dresses, zig-zagged, black and white prints and ruched, side split hems of silky eveningwear. He also introduced tough elements including hammered, metal eyelets, intricate laser cutting and weighted hems, alongside lacy, carved leather panels. Ever the perfectionist, Alaia often told in interviews how he would work through the night, exacting and hand-pressing his designs.

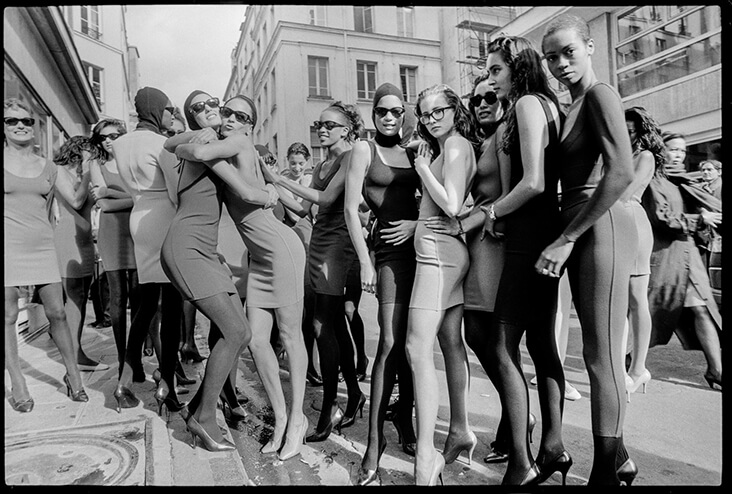

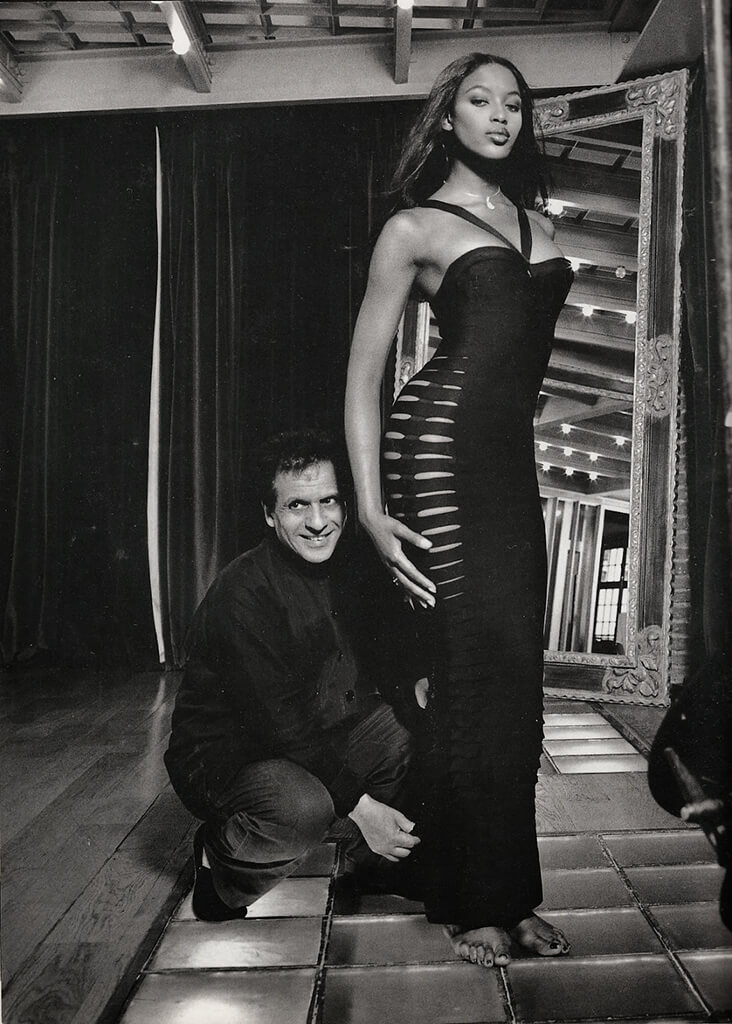

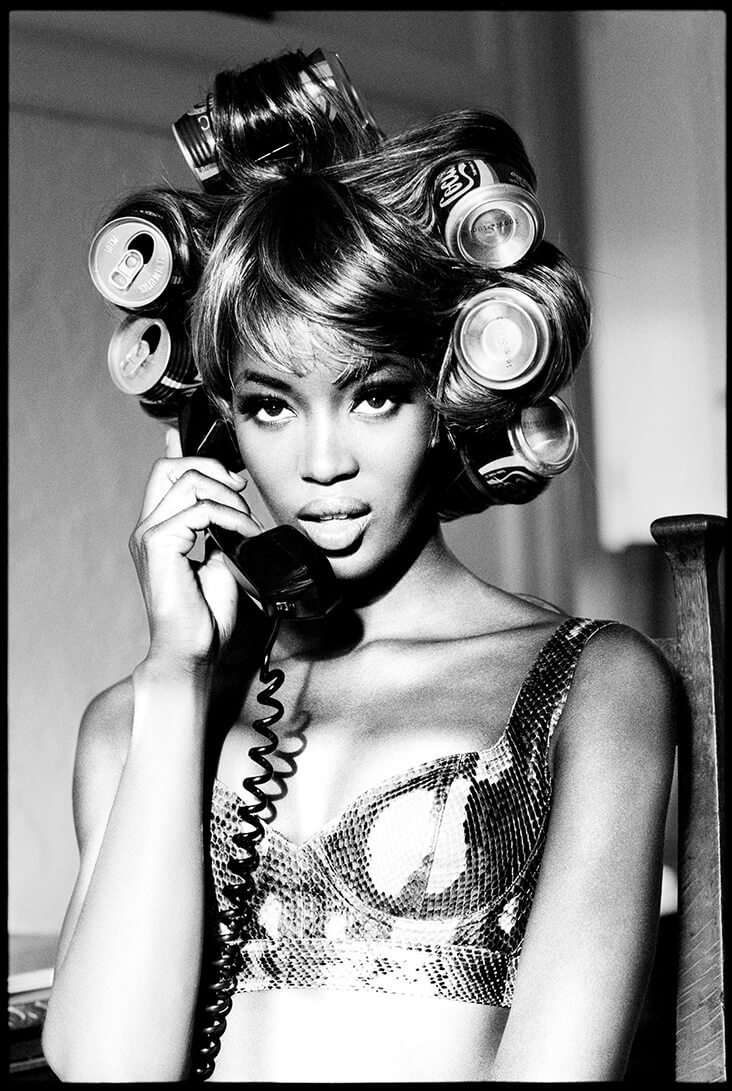

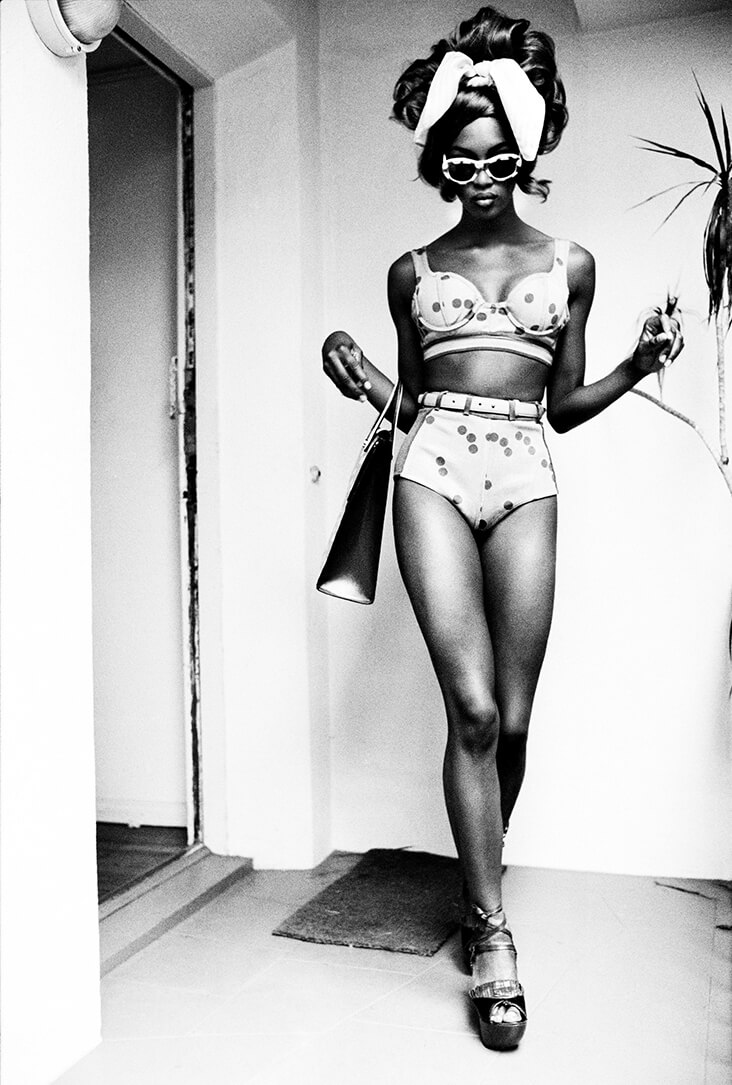

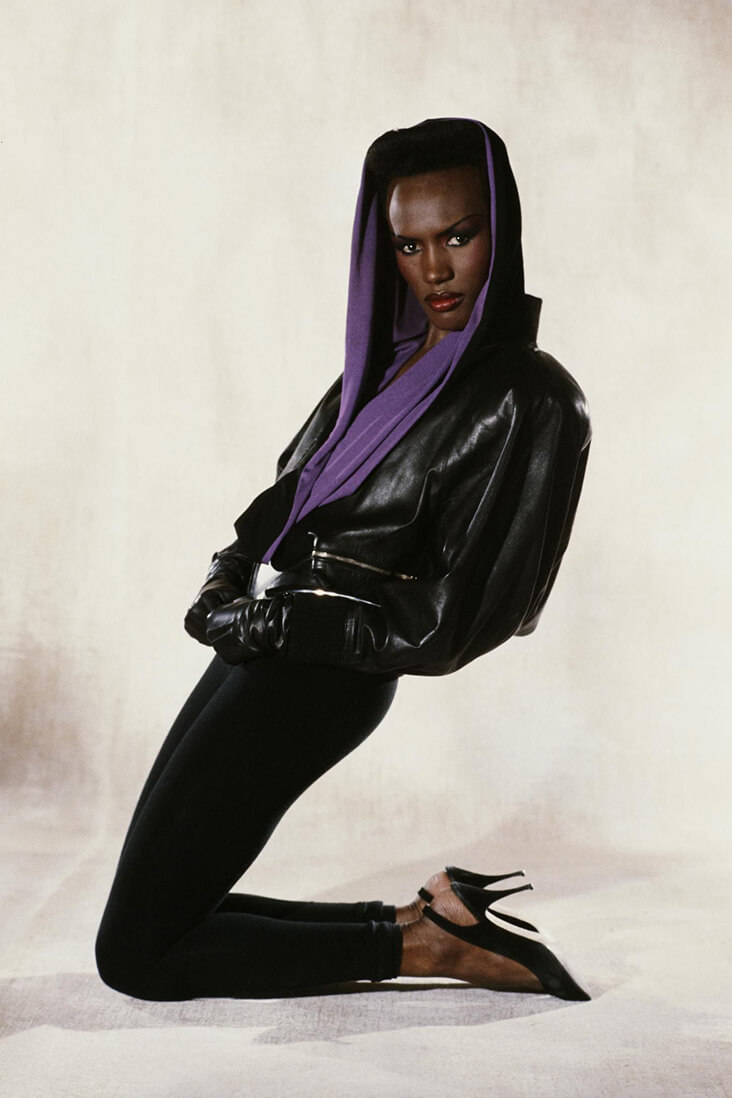

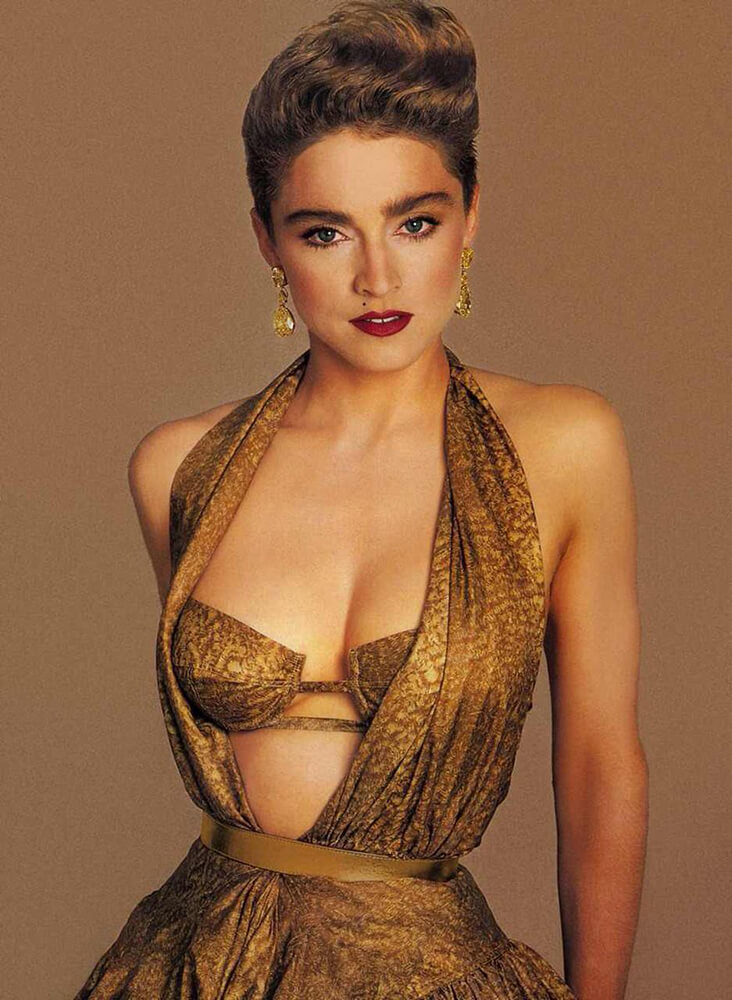

Parisian buyers were initially shocked by the sexy, clingy silhouettes of Alaia’s streetwear and sales in Paris were slow to begin with, but when both French and American Elle magazines sang his praises, New York’s department store Barney’s bought his entire line and commissioned more. Sales gathered pace across France and the United States and by 1988, Alaia had opened stores in Beverley Hills and New York. The late 1980s became Alaia’s defining era, as his skin-tight, body-hugging contours adorned powerful women unafraid of celebrating their femininity including Madonna, Grace Jones, as seen in the Bond film A View to a Kill, Tina Turner in her private dancer era, and, perhaps most famously, the supermodels of the age, including Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford and Naomi Campbell. In Campbell, particularly he found a lasting muse, becoming a kind of father figure who supported her through the early days of her career as a naïve teenager, all the way into adulthood, and she came to call him Papa. Colours epitomised his vision of feminine strength, ranging from girlish pinks or fawns to golds and striking reds, but black was the one he returned to again and again, commenting, “I like black, because for me it is a very happy colour.”

A somewhat unlikely hero, Alaia dressed predominantly in black, oriental collarless jackets and kept his personal life shielded from the press, preferring for his clothing to do the talking, a stark contrast to the outspoken, high profile women who adored his clothing and the way it made them feel. He also earned a maverick status for revealing his collections less frequently and outwith the formal fashion seasons, and for refusing to take on glossy, commercial advertising, a position he could only maintain due to the high demand for his exquisite craftsmanship. Naomi Campbell remembered the dresses he made for model Stephanie Seymour’s wedding, which allegedly took him over 1,600 hours to create: “I remember at Stephanie Seymour’s wedding … he was still stitching our bridesmaid’s dresses. He cannot let (his work) be seen until it is completely finished.” She added, “He’s an artist at the end of the day and he doesn’t have any sense of time.”

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Alaia’s live-in warehouse space in Marais, which he had been developing since the start of his career, took on a multifunctional role as home, shop, restaurant and gallery. Much like the atelier of Paul Poiret from the 1930s, Alaia’s workshop became a space for lavish events and gatherings, where designers, artists and socialites could mingle and share ideas. Here he would stage his own exhibition-like openings of his collections based around his own schedule, while also opening the space up to other likeminded designers, including Vivienne Westwood. Rejecting the formalised fashion-machine was a move that likened his clothing more to the realms of fine art, but it was also a powerful commentary on what Alaia saw as the wasteful, excessive state of the fashion industry, where the emphasis is, as he has said, on quantity, mass consumption and financial gain as opposed to creative merit. “The present fashion system is too hard – there are too many collections,” he observed, “The designers have no time to think! Money is too important. Schedules are too crazy.” Such pressure was, as Alaia saw it, the likely cause for controversial designer John Galliano’s public breakdown in 2011.

Azzedine Alaïa holding his two Yorkshire terriers, Patapouf and Wabo, walking in a Paris street with model Frederique van der Wal, who wears one of his creations, a black leather zippered dress / Photographed by Arthur Elgort, Vogue / February 1986

As his success grew in his later years, Alaia’s criticism of the fashion industry didn’t end here, and his strong opinions often lost him the support of vital fashion contacts. He famously had a feud with Vogue editor Anna Wintour after she failed to include him in her Model as Muse exhibition at the Costume Institute in 2009, hitting back with the jibe “who will remember Anna Wintour in the history of fashion? No one.” Wintour subsequently banned all US Vogue staff from attending an Alaia fashion presentation or catwalk show. Alaia also openly blasted the commercialisation of Karl Lagerfeld’s image, describing him as a “caricature,” while Lagerfeld fought back, criticising Alaia’s unwillingness to compete with the pace of the fashion industry by arguing, “When you are running a billion-dollar business, you must keep up.”

In 1995, following the death of his twin sister, Alaia took a partial retirement for several years, only maintaining work with his private customers and presenting work to a small selection of hand-chosen industries in his studio. Offers came flooding in for him to take over several major fashion houses during this hiatus, including Dior, although he refused to be a part of the well-oiled fashion machine that would dictate a working pace for him. Prada bought a stake in Alaia’s fashion house in 2000, leading to an upsurge of interest in his designs – with Alaia’s direction they subsequently developed a range of footwear and leather goods with stud details and cutout designs. But after buying back his stake from Prada in 2007, Alaia later sold it to the Richemont group, who own Cartier and Chloe, finding them less dogmatic and demanding. Alaia famously staged a comeback catwalk show in 2011, announcing to the fashion world that he was back in business, a move which received a standing ovation and rave reviews.

When a retrospective was staged in celebration of Alaia’s extensive career at the Palais Galleria and Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2013, Christina Catherine Martinez for Artforum magazine described the timelessness of his legacy, likening it more to the work of an artist than a designer: “The 40 decades of Alaia’s work shown here reveals no defining trends, only an increasing interest in the refinement of technique, a kind of reverse neoclassicist ethos that lends soft flesh and airy fabric the smooth, uncanny weightiness of sculpture.”

In 2017 Alaia passed away, but by then his place in fashion history was set, as a voice who could combine the artistry and skill of sculpture with an innate understanding of the female form. This ability to enhance a woman’s body without giving too much away remains his strongest legacy, one that has shifted the template of fashion history, and lives on through the body hugging, crafted silhouettes of Nicolas Ghesquiere, Herve Leger and Riccardo Tisci. Commenting on the individual choices he made and the hard-won freedom it eventually earned him, Alaia asserted, “I refuse to do things that I don’t want to. I do what I want. I am free.”

4 Comments

Vicki Lang

What a wonderful free spirit. Azzedina Alaia had some spunk. He didn’t play by the rules. Don’t you love it when the outcast wins. Thank you for the great article.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you – yes, indeed, he was an inspiration!

Sherry Berbit

Loved this, Rosie. Beautifully written and intriguing. Especially enjoyed the pictures of his incredible clothes on his muses- just beautiful. Thank you!

Rosie Lesso

Thank you for the feedback – so glad you enjoyed reading it!