Pierre Cardin: Fashion for the Space Age

“The clothes that I prefer are those I invent for a life that doesn’t exist yet – the world of tomorrow.”

Shiny, thigh-skimming boots, skin-tight synthetics, stretchy knits and micro-miniskirts; these were the epoch defining looks of Pierre Cardin. Like many of his generation, Cardin embraced the arrival of the Space Age in the late 1950s with great gusto, envisioning a future world made of day-glo, candy coloured plastic, vinyl and neon. His sci-fi take on fashion came to define the rebellious, avant-garde attitude of a new, 1960s youth culture, who rejected the old-world glamour of the 1950s in favour of a new, industrialised future. Though less of a household name, perhaps, than his recent contemporaries, including Coco Chanel and Christian Dior, Cardin’s legacy is just as important, as revealed in a huge retrospective at New York’s Brooklyn Museum from 2019-20, revealing the lasting influence he has had, not only on mainstream 1960s fashion, but the templates we continue to know and love today.

Although he is known today as a Parisian, Cardin was born Pietro Cardin in San Biagio di Callalta in Venice, Italy, in 1922, the youngest of 10 siblings. His family quickly fled to Saint-Etienne in France to escape the rise of fascism when he was just 2 years old, changing his name from Pietro to the French version, Pierre. Working as a couturier’s apprentice aged 14, Cardin moved on to work for a tailor in Vichy, specialising in women’s suits. In 1945, following the end of the war, Cardin moved to Paris and took on an apprenticeship with the famous couturier Jeanne Paquin, where he helped create costumes of French Surrealist artist Jean Cocteau’s iconic film Beauty and the Beast. A hard worker, Cardin quickly moved on to work with prestigious designers including Elsa Schiaparelli and Christian Dior, learning enough tricks, skills and connections to quickly progress. “Designers like Pierre Cardin are the future of haute couture,” praised Dior, after Cardin helped him launch his pioneering ‘New Look’ of the 1950s.

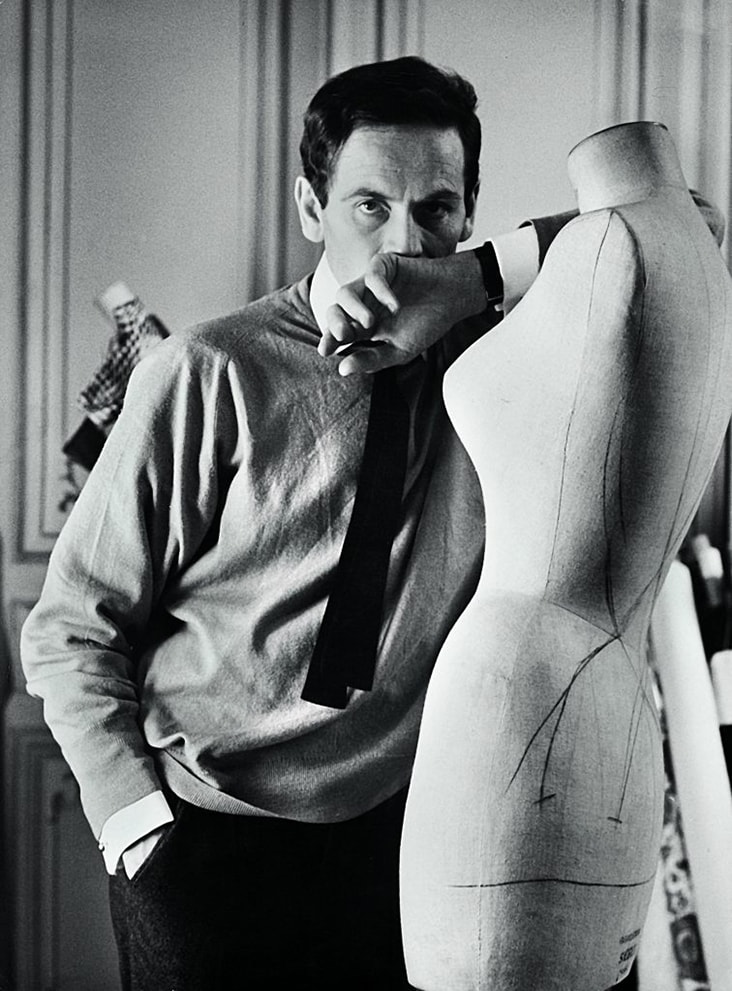

Venturing out alone, Cardin started out as a costume designer for stage and theatre, investing in his designs a playful, outlandish quality which would remain for the rest of his career. Dior invited Cardin to create a series of costumes for the flamboyant, multi-millionaire art collector and socialite Carlos de Beistegui, who was planning a Venetian themed “party of the century.” Launching into the commission with relish, Cardin produced around 30 extravagant, outlandish costumes, including a lion’s mane garb for Dior, and a fabulous feast of clothing for many other guests, launching Cardin’s reputation amongst the Parisian elite.

By the early 1950s Cardin had branched out into fashion, hoping to tap into the commercial potential of the mass market. His first couture collection was presented in 1953, with unusual, experimental shapes including his iconic bubble dress, a play on Dior’s 1950s, nipped in waist and full skirt, but with a gathered hem, which quickly gained critical acclaim. Another signature look from this time was his long, tailored and boldly coloured coatdress, with detailed panelling on the reverse. Garments were made with luxury in mind, from crisp textiles including wool, crepe and jersey in conjunction with the Italian firm Nattier. Within a year, Cardin had become a whirlwind success, attracting celebrity clients including Elizabeth Taylor and Brigitte Bardot, who wore his designs in movies and magazines, promoting his clean, modern look to a wide audience.

Ever the progressive, forward-thinker, Cardin was the first French couturier to launch a ready-to-wear, commercial collection for the mass-market, forming an alliance with Printemps department store. So affronted was the French haute couture guild by this “cheapening” act, that they threw him out, only allowing him back in years later. The move from elitist, glamorous couture to the more profitable, middle class market revealed his savvy business acumen, making him rich, and influencing countless designers since. Cardin launched his first menswear collection in the late 1950s, with a series of mod styles in bold, pop colours aimed at youth culture with an understanding that, “most men have a subconscious, but inhibited longing for fantasy.” Targeting a young audience, he persuaded students from the University of Paris to model his first menswear collection, channelling architectural lines, eye catching motifs, collarless jackets and roll neck sweaters. A high point for his trailblazing menswear designs came in 1963, when he was invited to design a series of collarless suits for The Beatles.

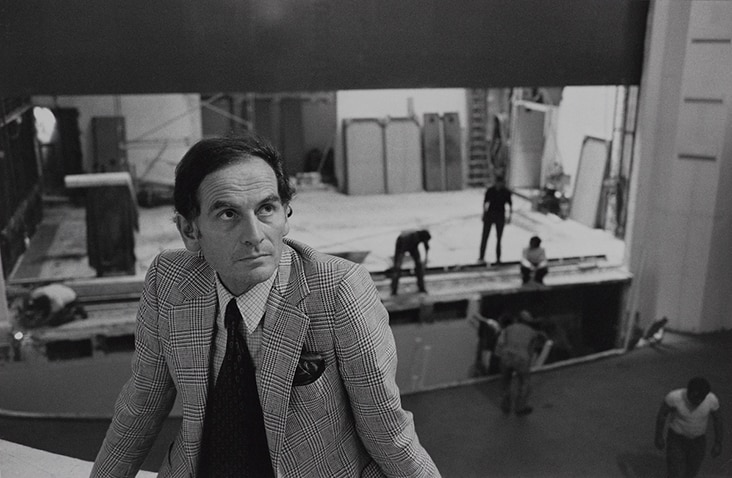

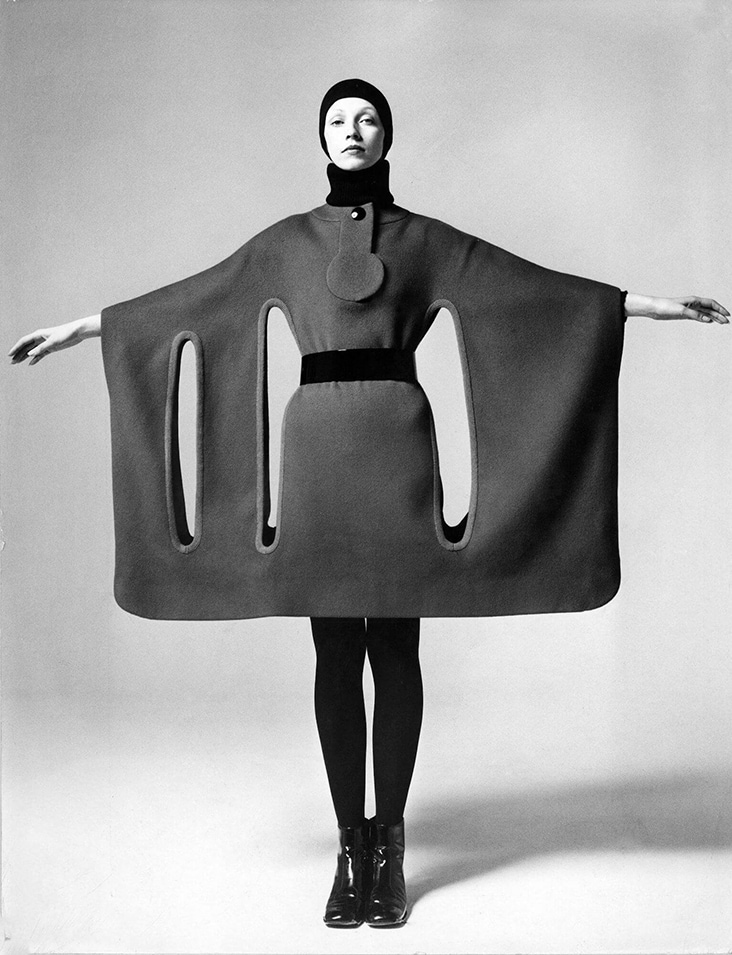

Following on this success, the 1960s truly launched Cardin’s career into the international spotlight. Embracing the optimistic anticipation of the Space Age, Cardin produced a series of designs which looked towards the future, envisioning the kind of outfits men and women might wear on the moon in fifty years’ time. Genuinely fascinated by space, Cardin made a visit to NASA headquarters, quizzing officials on what people might wear in space and even trying on a spacesuit. Revolutionary designs from this period included his unisex, cosmocorps suits and porthole dresses, as well as plastic visors, masks and crash helmets, all produced in synthetic, high gloss technicolour. Hats and headwear were vital to his vision, a wearable play on the space helmet motif. Writer, artist and designer Cecil Beaton observed, “…his young models are equipped for any science-fiction activity … they are silhouetted like pears, torpedoes, or rocket missiles… They are in advance guard of those exploring outer space.”

Curator Pamela Golbin also points out how Cardin’s Space Age designs were a potent symbol of rebellion in Paris at the time, calling them “a metaphor for youth and the future of France.” Unlike London, in Paris there was no mod/rocker scene as such, but by embracing futuristic fashion and ideas, young people found the means to reject the staunch traditionalism of the 1950s, with its’ post-war austerity, traditional glamour and old-world charm, as Golbin explains, “(The Space Age) was an optimistic message about how you can transform yourself into a modern person by wearing mini-skirts, trousers with stretch, and other clothes that let you move.”

The unisex androgyny of Cardin’s designs also proved popular with the 1960s youth culture, at a time when the rise of the Women’s Movement meant boundaries between men and women’s roles in society were blurring, traditional family values were being questioned and more open, fluid approaches to gender and sexuality were being embraced. Another tech revolution spearheaded by Cardin was the use of LED lighting, in his robes electroniques, from 1967; featuring light-up strands of embroidery, his designs lit up a darkened runway, dazzling audiences with a vision of the future. In 1967, Cardin caused another sensation with his children’s wear collection, gathering all the triplets from Paris to be photographed wearing his simple, clean, streamlined outfits, patterned with his trademark, modernist geometric motifs.

Raquel Welch in a Pierre Cardin outfit featuring a miniskirt and necklace in blue vinyl, worn with a Plexiglas visor / Photo by Terry O’Neill / 1970

Since this time, Cardin has continued to produce radical, surprising designs, including eyewear, furniture and the introduction of Cardine, his own fabric, which could be heat treated to form sculptural, three dimensional forms, prompting his moniker as “fashion’s scientist.” Now in his 90s, Cardin has stores and boutiques established around the world that sell fashion, accessories and perfumes, along with a permanent museum set up in Paris to showcase his most iconic designs, the Musee Pierre Cardin.

However, many would argue it is his contribution to 1960s youth culture that has left the greatest mark in fashion history; a series of major retrospectives since the 1980s have celebrated his contribution to the era, including the current display in Brooklyn, which brings light to his most ground breaking ideas for a new generation. As this display reveals, the designs he pioneered at this time continue the shape the clothing we wear today, from thigh-high boots to micro mini-skirts and voluminous, bubble silhouettes in sunny, optimistic colours, once futuristic designs which now have a retro, nostalgic vibe, encapsulating the burgeoning, hopeful optimism of the 1960s. “I was very lucky,” wrote Cardin, “I was part of the post-war period when everything had to be redone.”

Leave a comment