Paul Poiret: Fashion’s First Modernist

“I do not want all women to look and dress exactly alike. I want them to be as different in their dress as they are in their personalities.”

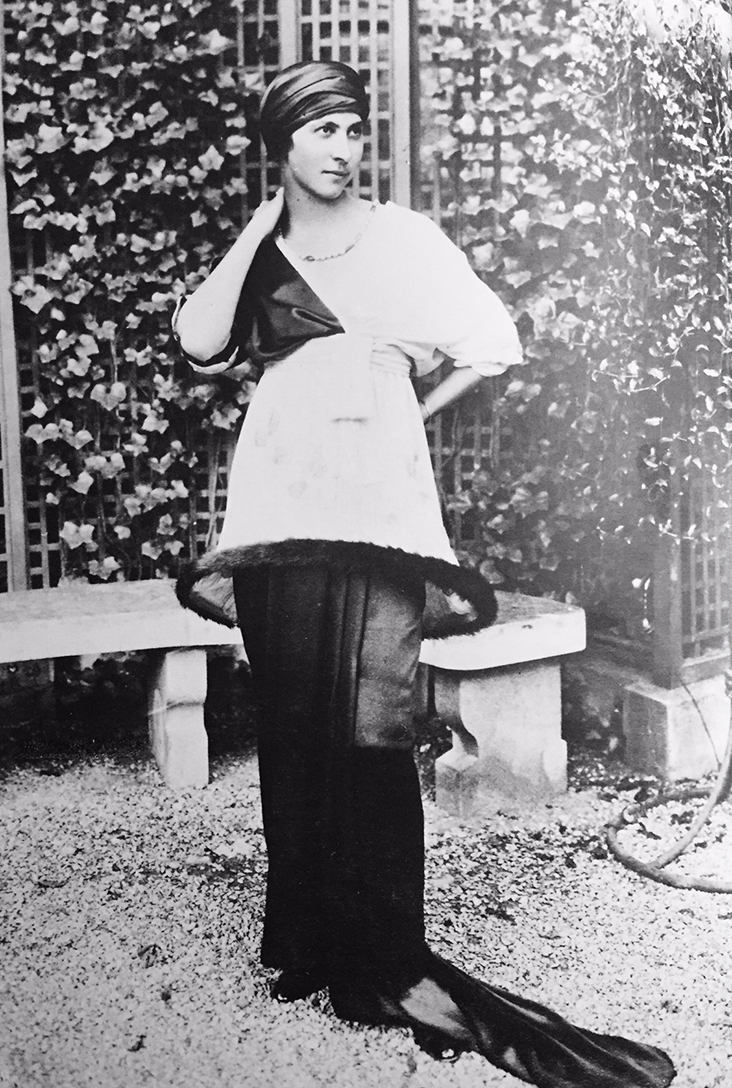

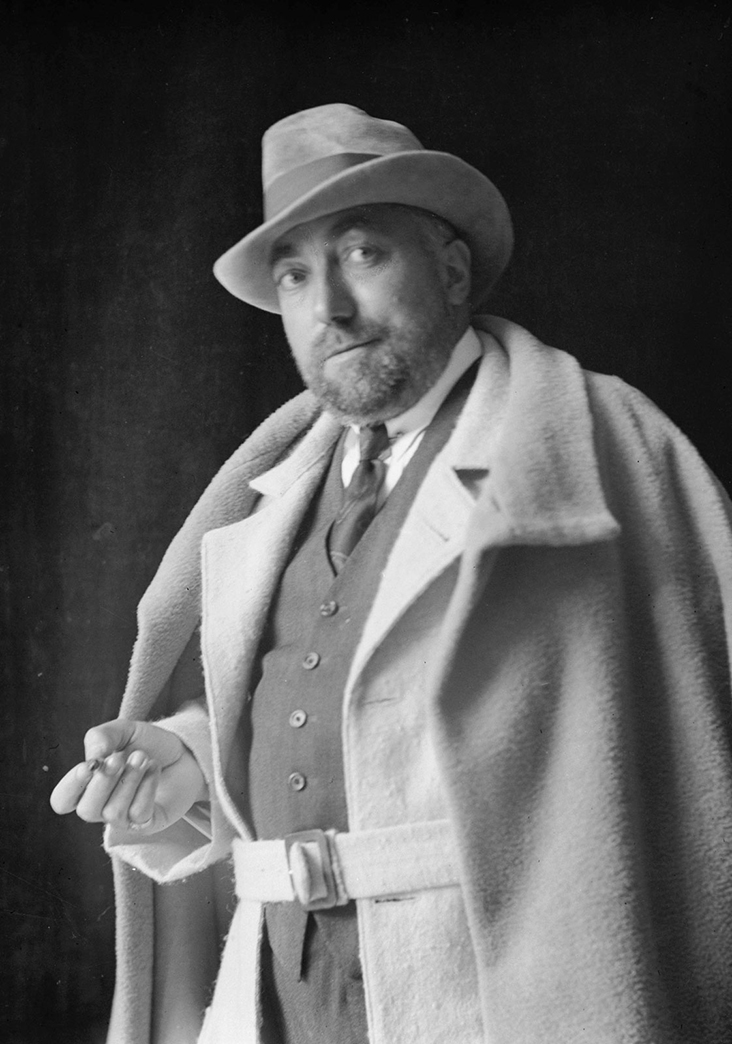

Paul Poiret the man was as bold, brazen and uncompromising as his fashion. At the height of his career in the Parisian Belle Epoque era, America crowned him the “King of Fashion” while Paris called him simply “Le Magnifique.” A lover of the exotic and Oriental, Poiret’s vibrant, tropical colours, free flowing dresses, sultana skirts, turbans and harem pants liberated women from Victorian corsetry and lace, heralding the rise of a newly emboldened silhouette. But his multiple interests in art, theatre, drama and design were arguably the most pioneering elements of his practice, allowing him to blur boundaries between fields and cultivate an open, enquiring approach that would be instrumental in the development of Modernism. Though fashion was his oeuvre, he was quick to declare, “I am an artist, not a dressmaker.”

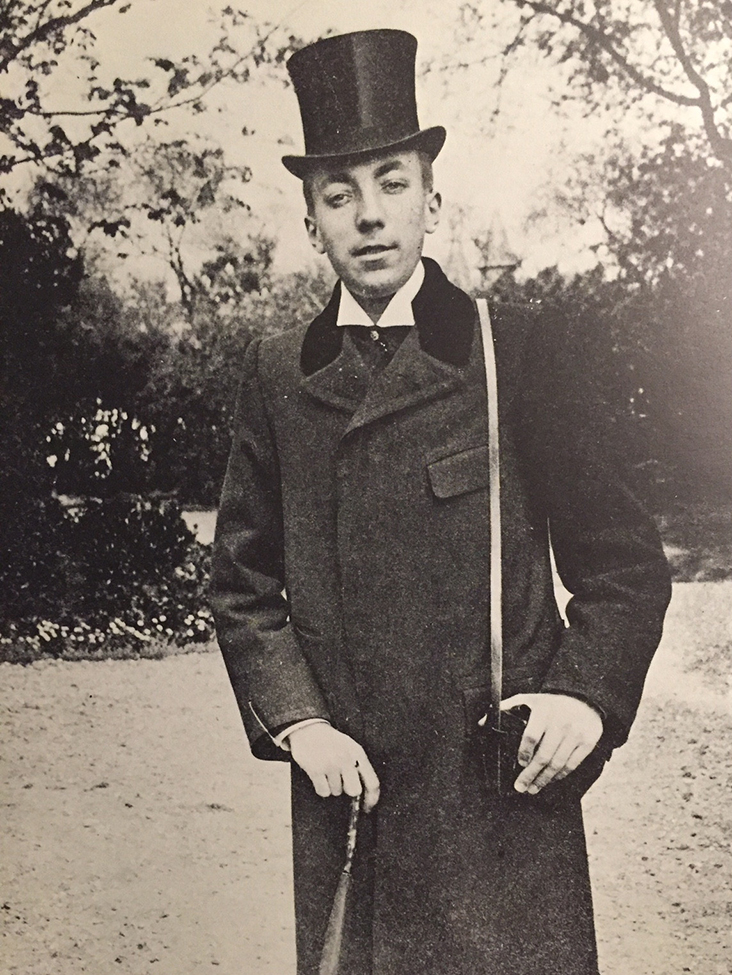

Poiret was born and raised in Paris, where his father ran a local drapery. With his parents and three sisters, he lived in an apartment above his father’s shop, which was artfully decorated, but it was the family’s country home outside Paris that opened up Poiret’s creative spark, giving him room to get messy, press flowers and gather scrap metals like a magpie.

The family relocated to a larger house when Poiret was 12, but he was not there long; when his sisters all caught scarlet fever he was swiftly packed off to boarding school for protection. Uninspired by his teachers, he sought his own paths of interest, soaking up the lavish pages of fashion magazines and art catalogues or visiting museums and art galleries. Poiret’s practically minded parents still exerted a powerful influence on him and after finishing school his father pushed him to train as an umbrella maker. Though the technical skills he learned would serve him well in the future, the narrow discipline of the trade left him feeling trapped – as an outlet he would draw his own clothing designs before making them on his sisters’ wooden mannequin, sometimes incorporating samples of parasol silk pinched from his employer.

After building up a substantial body of work, Poiret set out to find a mentor to guide him forward. One of the clients he presented his dresses to was the couturiere Madeleine Cheruit at Maison Raudnitz Soeurs – she was hugely impressed and promptly bought twelve of his designs, encouraging him to bring more her way. The early commercial success of this work earned Poiret a steady job with the prominent couturier Jacques Doucet, who focussed on luxury clothing for wealthy clientele. It was here that Poiret made his famous striking red wool cloak, a runaway success that sold over 400 times. Doucet helped Poiret to find work designing stage costume for various prominent actresses, which caused quite a stir, particularly the mantle he made for actress Rejane in the play Zaza. Her costume was composed of hand painted black tulle and taffeta; Poiret remembered later in life the impact the dress had on his career: “All the sadness of a romantic denouement, all the bitterness of a fourth act, were in this so expressive cloak, and when they saw it appear, the audience foresaw the end of the play … Thenceforth I was established … in all of Paris.”

A confident and charismatic character, Poiret was the life and soul of the party, but his decadent lifestyle came to an abrupt end in 1900 when enforced military service dragged him into the Army for nearly a year. On his return to Paris he found work with Maison Worth, a haute couture company run by the two brothers Gaston and Jean Worth. It was hoped Poiret would create casual daywear for their house, with a focus on wearable comfort. Poiret ran with the brief, producing high waisted empire line dresses, tubular shapes, kimono jackets and long skirts influenced by various sources including African and Oriental dress, or classical Roman drapes. His designs proved popular, not least because they loosened the restrictive corsetry of the Victorian era, allowing women to breathe. The two brothers had mixed feelings about his designs; Gaston was quickly impressed, but Jean less so, referring to his loose silhouettes as a lowering of their design standards and even calling them “dishrags.” Real trouble came when Poiret presented a straight, black wool cloak to the ageing Russian Princess Bariatinsky, who found it far too simple and refined for her conservative tastes, declaring, “What horror; with us, when there are low fellows who run after our sledges and annoy us, we have their heads cut off, and we put them in sacks just like that.”

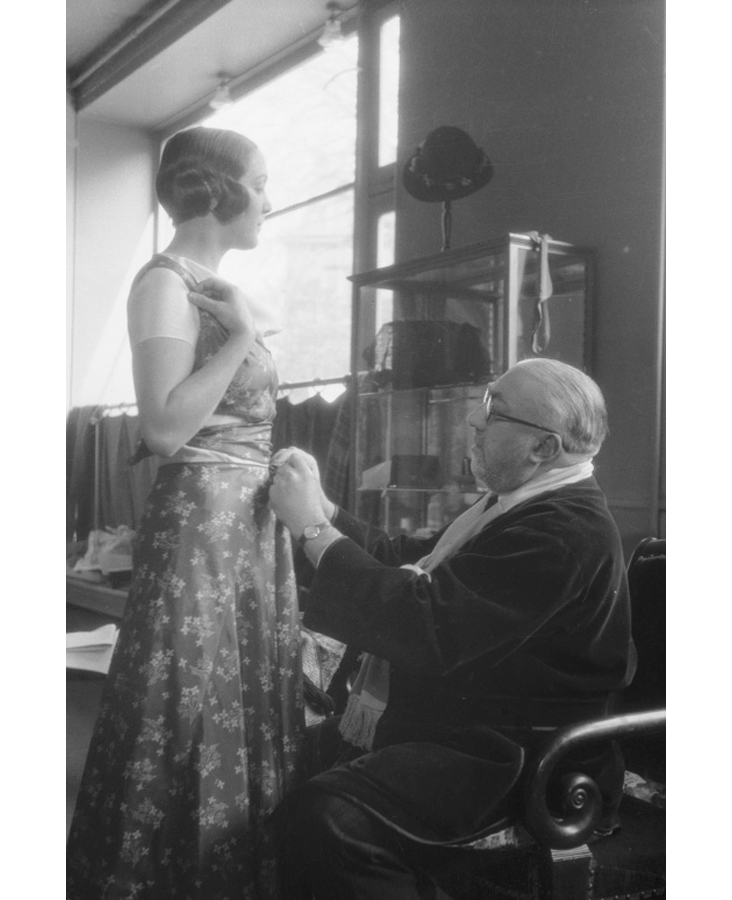

By 1903 Poiret was, as his biographer Palmer White wrote, “tired of antagonism and wanted to strike out on his own.” His father had died, but Poiret’s mother was able to lend him a modest sum of cash to establish his first store at the small No. 5, Rue Auber. Determined and ambitious, Poiret put his theatrical showmanship to good use, displaying a series of eye-catching window displays that were soon pulling in a steady stream of customers; within a month, he was already making a return on his profits. With tenacity Poiret turned the black cloak rejected by the Russian Princess into a commercial success, laughing back at the criticism by titling the work the “Confucius Coat” after the ancient Chinese philosopher, to reveal the Oriental influence on the design, while adding, “every woman had one.”

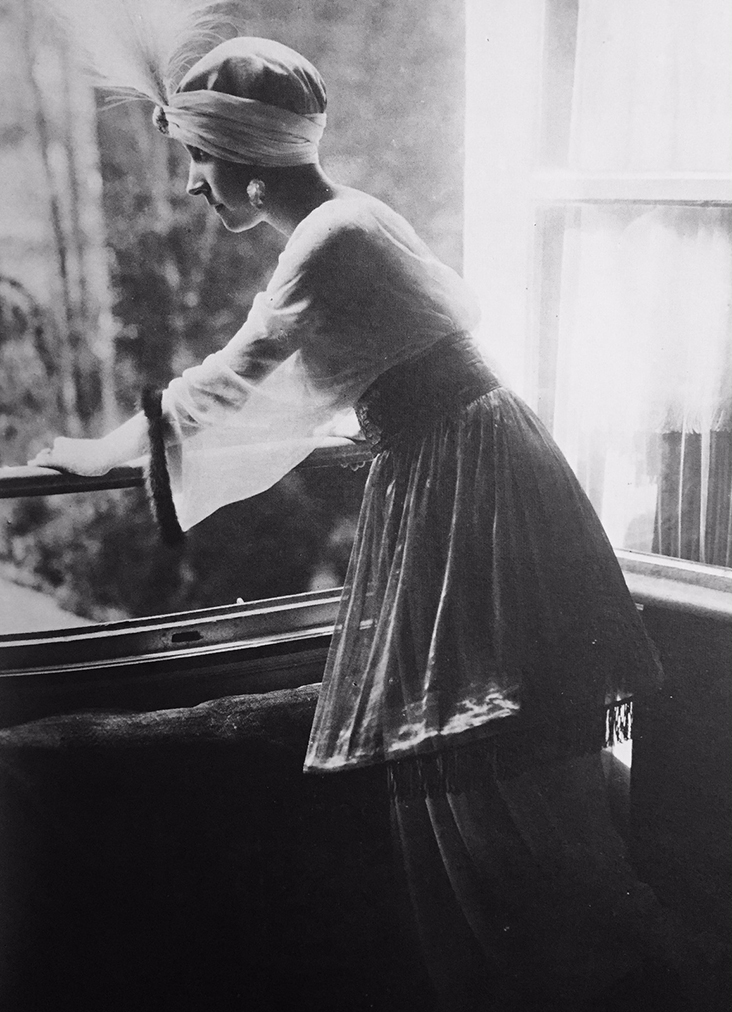

Like many creatives of his generation, Poiret was fascinated with Asian visual culture, embracing the wonder of the far flung and exotic through striking patterns and shimmering fabrics. This ideology reflected a wider societal disillusionment with dehumanising industrialisation that had swept across the West, while lavishly decorated, hand-made artefacts being displayed in rising ethnographic museums across Europe seemed closer to the innate human spirit. Poiret even began curating his own collection of precious objects which came to inform the shape and pattern of his designs and styled himself as a sultan from the Arabian folklore tales in One Thousand and One Nights, 1704. The first couture trousers for women that Poiret pioneered revealed this Eastern influence, forming a pantaloon or dhoti shape, which, when made in silky, flowing, jewel toned fabric could create an understated, refined elegance.

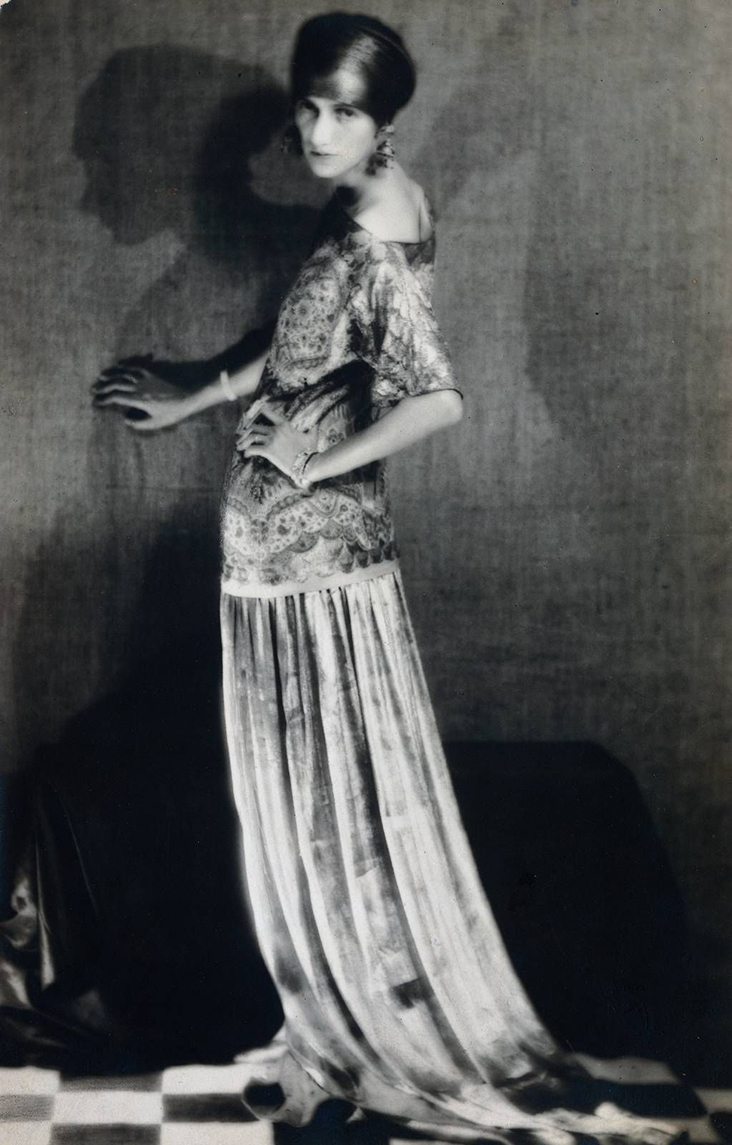

Other wearable designs for women included his lampshade tunic, with its fluted hem, and the brassiere designs he helped popularise as an alternative to the corset, offering women a newfound comfort. That his designs were based on drapes and rectangles made them progressive and Modernist, symbols less of sexual desire and more progressive freedom. The revolutionary act of breaking away from the confined dress code stirred up huge amounts of controversy as women brave enough to embrace this newfound liberation faced public heckling and even acts of violence. In contrast, the straight, tight hobble skirt Poiret presented was less than liberating, complicating his relationship to feminism, as he liked to joke, “I freed the bust, but I shackled the legs.” Nonetheless, the silhouette the hobble skirt made was an entirely new aesthetic that was still seen by many as a form of transgressive rebellion.

The rising success of his business led Poiret to move to a larger premises at the Rue Pasquier, where he could both live and work. Combining living and commercial space in this way was unconventional and raised a few eyebrows, but the controversy had little impact on his commercial success. With his business firmly established, in 1905 Poiret married his childhood sweetheart Denise Boulet. The pair travelled widely around Europe together, before going on to raise a large family of five children. In a Vogue interview Poiret cited her as his main source of creativity, saying, “My wife is the inspiration for all my creations; she is the expression of all my ideals.” Denise Poiret’s tall, slender figure would come to inform Poiret’s famous dropped waist garconne dresses, which paved the way for the 1920s and 30s flapper era. As his successful business, and his family, continued to expand, Poiret set up home in an 18th century mansion on the Right Bank, where he became known for lavish, extravagantly organised parties, which included theatrical productions, exotic animal displays, dancers and orchestras, often with a flamboyantly Eastern theme.

Ever the ambitious entrepreneur, Poiret extended into a range of new directions. He established his own design school in 1912 called Martine, named after one of his daughters, where he encouraged his students to work in an unstructured, experimental way, later leading to the foundation of his fashion brand Maison Martine. He also began a series of successful collaborations with illustrators and artists, likening the creative act of dressmaking to the process of producing art, stating, “Am I a fool when I dream of putting art into my dresses, a fool when I say dressmaking is an art? For I have always loved painters and felt an equal footing with them.”

One of his earliest collaborations was with artist Paul Iribe in 1908, who Poiret commissioned to draw his clothing designs onto characters with careful, intricate detail; the resulting artworks were printed in the publication Les Robes de Paul Poiret, Racontes par Paul Iribe. A similar publication followed between Poiret and the artist Georges Lepape titled Les Choses de Paul Poiret vues Par Georges Lepape. Poiret’s canny business sense and naturally sociable character allowed both parties to benefit; the artists gained commercial exposure, while lavish drawings gave credos to his designs. Combining illustration and design in this way raised greater public interest in fashion illustration, leading to the establishment of fashion publications including Gazette du Bon Ton.

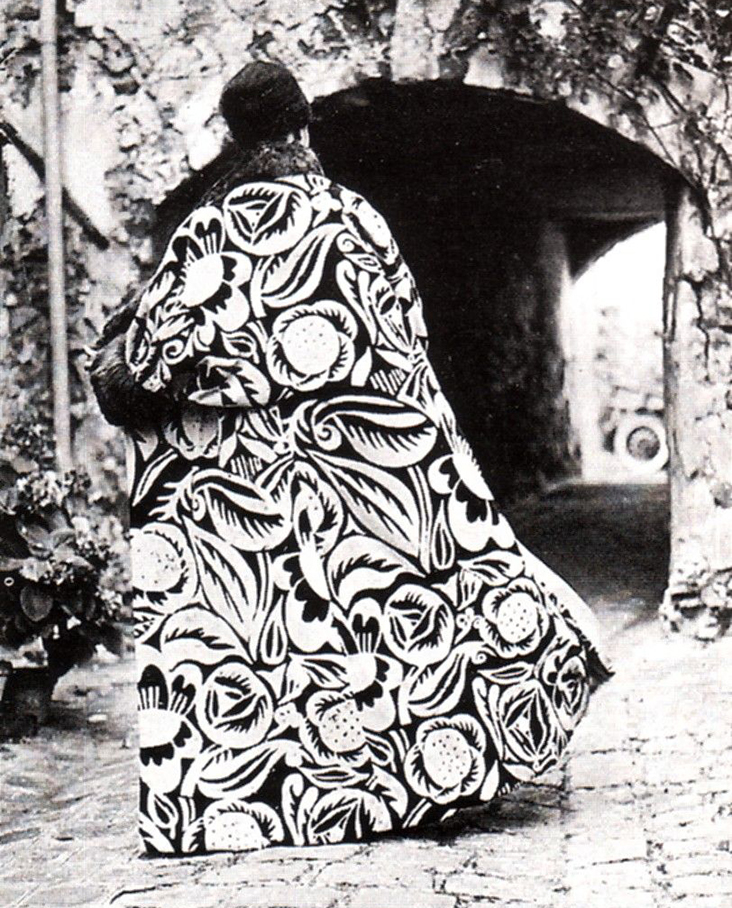

Poiret spotted the work of the young Fauvist painter and printmaker Raoul Dufy around this time and initially commissioned him to produce woodblock branding for the stationary of his fashion house. But he was so impressed with the end results that he asked Dufy to create a series of hand printed textiles for him. The resulting bold, vibrantly coloured floral designs would become the dramatic backdrop for some of Poiret’s most famous items, including La Perse and the Bois de Boulogne, which caused quite a stir amongst Parisian society. Poiret continued to work with artists in this way, feeling a close affinity with their methods, writing, “It seems to me that we practice the same craft and that they are my fellow workers.”

During the First World War Dufy was called into the military, where he served as a military tailor, but the horrors of war left him so traumatised he spent a long spell in Morocco recovering. On his return to Paris his business resumed, while his empire broke new ground, delving into perfume and interior décor. He also conquered the United States in the following years, finding adventurous clients including Peggy Guggenheim and Nancy Cunard who revelled in the rebellious nature of his designs.

In his later years Poiret’s light was being eclipsed by new rising stars in the ever-expanding Parisian realms of haute couture. The sporty, minimal and utilitarian aesthetics of Coco Chanel influenced many designers, but Poiret refused to change his house style. When Poiret asked the perpetually black wearing Chanel who she was mourning, she replied coolly, “You, Monsieur.” Poiret’s business closed in 1929 and he spent the remainder of his life focussing on the production of art, particularly painting, remaining creatively motivated until his death in 1944.

Although the lavish Orientalism Poiret promoted fell from popularity in the austere, post-war period following his death, since this time, Poiret has become widely recognised as a pioneer of Modernism, one whose technical innovations, clean lines and simplified shapes became the launchpad for a brave new kind of fashion. But perhaps most radical was the playful, adventurous approach he took to fashion, an ethos that has influenced some of our most progressive voices since, including the punk aesthetic of Vivienne Westwood, the unconventional shock tactics of Alexander McQueen and the whimsical outrageousness of John Galliano, true artists, who, like Poiret have followed their own singular vision to success.

One Comment

Laurence Dyck

Lovely article! I was vaguely aware of Poiret before from looking at ’20s fashion a few years ago, but I just saw lampshade tunics and thought, ‘ugh’ and moved on. Your article has me looking at that alternative fashion in a new light – and it’s a fun and stylish diversion from all the typical dancehall fringed flapper dresses that you usually see when you first look into the clothes of the era (although I do love those, too!)