3: Our relationships with design and craft

Craft and design are important to us today. They provide tangible and stable objects in our modern, often stressful, lives. It is possible for objects to have meaning beyond use value. I want to focus here on how we interpret designed or crafted objects.

Design is everywhere is a truism we all understand. We need to filter this deluge of objects. Just as we filter out background noise, so we filter the objects we use: we might remember the serving bowel used at dinner, but not the knife we used to prepare the food?

We need the filter to stop us becoming mad, and maddening consumerists!

“I love absorbing and observing the beautiful and ever-changing light on the Isle of Skye. My spoons are inspired by the delicate qualities of nature.” via The New Craftsmen

This filtering, or separation, is mirrored in design appreciation, and design critique too. Often, each is seen as two distinct sets of issues: the spiritual and haptic feeds our appreciation, whilst an aesthetic and manufacturing focus delivers our analysis of objects. The latter is seen in car design. When Henry Ford quipped about the Model T car “ [a]customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black” he is undermining colour, and in affect, prioritising technology and production of the first mass produced car, rather than any emotional engagement with the Model T.

Of course, in the intervening years advertising has striven to create emotional links to cars but we still focus on technical details when discussing our car: max speed, MPG or engine size. Whereas the opposite might be true for craft objects. Our appreciation of a large earthenware serving bowl for instance will often lead to a conversation as to its provenance: who made it? was it a thrift shop find? its weight, glaze or colour? Thus, we divide design into two spheres – one is technical “hard” design; and the other, a softer sphere. Which is informed by user-experience and an appeal to our senses.

Both approaches to understanding objects have their weaknesses. It can lead to a hollow experience to ignore the spirit of an object by focusing on its surface or utility alone. A reliance on the visual – the optics – can be misleading in how objects work in our lives. I think our relationship to objects is more holistic than the examples I have outlined.

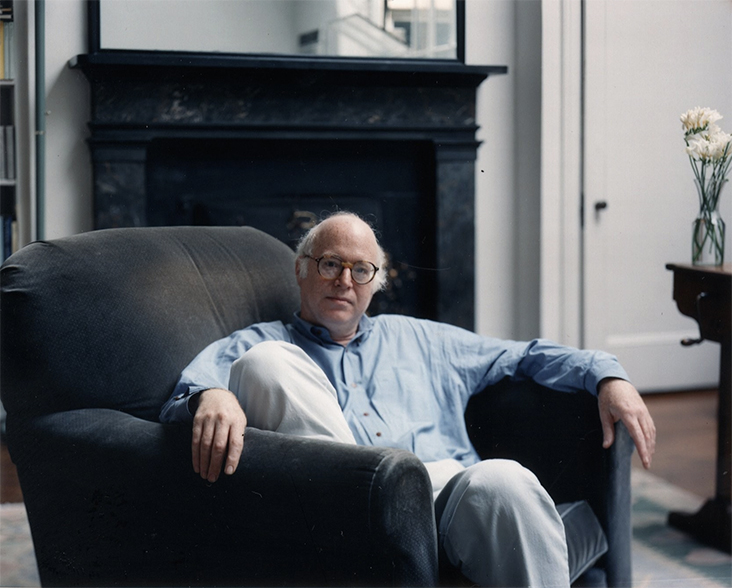

Richard Sennett is a writer who has looked at this relationship with craft and craftsmanship. In The Craftsman he provides a detailed history of Craft, and its many interpretations. It is an enriching story.

He looks at our relationship with craft. How materials like cloth and clay have meaning to us. He dedicates a chapter to investigate these relationships – he focuses on clay – but textiles too share the interactions he discusses in the chapter.

‘What makes an object interesting’ he asks.

In brief, he breaks our relationship to materials into three ‘issues’: metamorphoses, presence and anthropomorphosis. He defines these issues as the psychological catalysts to material consciousness. By which he means how do we learn to respond to, love and imagine design in our day-to-day lives.

Metamorphoses is when craft develops its techniques – from simple calico production, to dyed and patterned cloth, specifically designed for the body and fashion for instance. Presence, is when the anonymous artisan becomes a craftsman (sic) by individualization of the object. It might be simply signing the work, a maker’s stamp; or a particular characteristic in the production: a firing technique, or unique use of materials. And finally, anthropomorphosis is when we begin to imbue our objects with meanings beyond use value – we personalise the object and give it human like qualities.

The English oak Note Table by Edward Collinson was “inspired by the work of traditional coopers; the base of the table is created with individual ‘coopered’ staves, and the finish is fumed, a historic process that enriches and deepens the wood’s natural color.”

I want to explore an alternative, or supplementary way to understand our relationship to objects which is influenced by the notion of anthropomorphosis outlined by Sennett. And to this end, it is useful to look at the perceived differences in utilitarian design, from the handmade or craft-based design. Utilitarian does not have the complexities in meanings (or kudos) that we find in broader craft design. It does not necessarily have the marks of its maker or a direct link to where it was made. But what is interesting about utilitarian objects is how they grow in our hearts through use.

For example, a knife becomes our favourite knife not simply because of its cutting ability, which should be seen as a given, but because it begins to feel right in our hand. The weight is comforting in our grip. We develop a tactile relationship. Furthermore, the knife is the one you used when first preparing food for your child, when transitioning to whole food. Or you remember purchasing it in a shop now closed, or it was gift from a now long lost friend… thus the knife becomes attached to many narratives that are invisible when it is put back into the knife block. In a way, part of this process, of getting-to-know-an-object’ can be seen to be anthropomorphising our favourite designs. How often do we describe a coat, or objets d’art, as an old friend!

“I often visit the British Museum and the Natural History Museum, where I make sketches of ceramics and take notes of the handles, shapes and techniques.” Charlotte McLeish, Ceramicist via The New Craftsmen

Outside of any religious context, this spiritual and temporal connection to objects is often missed in the Western canon of appreciation and critique. But, I would argue, it is why craft and design are important to us today.

Of course, many people have distinguished between, as it were, hard and soft design. The dichotomy between the handmade and mechanical processes. But this is a disservice to both and places an overemphasis on the process. And this is not a new problem: Arts and Crafts and William Morris struggled with the synthesis between machine and handmade. A fear the former would erase the latter. But this is an analysis which, impart, ignores the individuals experience. How we turn objects, like the knife, into a whole storybook of meanings.

“Improvisation means the risk of failure, which energises the process and keeps my practice alive. I tend to make decisions during making, allowing an improvisational flow into the work. It’s about navigating possibilities and restrictions of the material, identifying ‘moves’, and staying very much in the present.” Jochen Holz GLASS ARTIST / Photo by Jochen Holz/Angus Mill Photography

In conclusion, it needs to be mentioned, there is a tension between consumer economics and the idea that objects become more important to us over time. Design needs to be consumed. Consumption is not something contemporary craft is immune to either. New galleries and shops sell and market craft, as a panacea to contemporary life. Or equally, as codified representation of taste. Taste is the catalyst for so much consumption – for good and bad!

Style will be looked at next…

Feature Image: Ceramics by Alison Lousada via matchesfashion.com

2 Comments

Pingback:

Boots Made in the UsaGaye Elder

I enjoy all of these essays, today’s was especially good, so I wanted to thank you particularly. I also enjoy hand stitching on your linen.