Jenny Saville: In the Flesh

“I paint flesh because I’m human. Flesh is just the most beautiful thing to paint.”

Jenny Saville’s voluptuous, rippling folds of flesh explore the living, breathing human experience. On one hand she is a painter’s painter, who relishes in the messy, smeary liquidity of oil paint, but she also draws parallels between the sensuality of painting and the perceptions of seeing, touching and living in human skin, as it squashes, flattens, wrinkles and overflows. Drawing on centuries of traditional nudes, her sensationalist paintings bring figurative art into the 21st century, a time when bodies are pushed to extremes and placed under scrutiny like never before. But hers is a woman’s vision, not as a voyeur, but as an inquisitive investigator, as she argues, “I wouldn’t make this work if I was a guy.”

Saville was one of four children, born to creative parents who actively encouraged her desire to make art. Growing up in a creaky old house in Cambridge her parents gave her a broom cupboard as a first studio, in which she remembers, “no one else was allowed in. I would wake up every morning and I just couldn’t wait to get in that room, because I always had something on the go.” Developing an early fascination with grown up women’s bodies, the young Saville was fascinated by her curvaceous piano teacher, secretly observing with curiosity the ways her body parts “pressed together” into one another.

But it was her Uncle, an art historian, who had the most marked impact on her younger years, encouraging her to think, read and draw in new and unexpected ways. When she was old enough he took her to Venice where she saw the great figurative paintings of the Old Masters including Titian and Tintoretto. He also introduced her to the real side of art practice by waking her at 6am to “draw at the fish market on the Rialto Bridge” and took her to the bars where artists used to hang out. Looking back, she recalls the impact of these experiences in teaching her “great art wasn’t something far away, it was part of life.”

Heading off to Glasgow School of Art, Saville admitted she was somewhat naïve about the oppression and exclusion of women from art history, explaining, “I never questioned my ambition. I never thought: I’m a girl, I can’t do this. It was only when I got to art school that I realised the great artists of the past were not women. I had a sort of epiphany in the library: where are all the women? Only then, as the truth dawned, did I start to feel pissed off.” At Glasgow School of Art in the 1980s daily, academic life drawing and human anatomy was a core component of her studying, something which she saw as fundamental to her development as an artist, lending her knowledge and skills which would become the backbone of her career. Her virtuoso talent soon caught the attention of her tutors who awarded the young Saville a series of prizes, including a six month scholarship to Cincinnati University. While there, she was fascinated by the obese women walking around shopping malls and began painting her signature larger than life nudes with her trademark painterly hand.

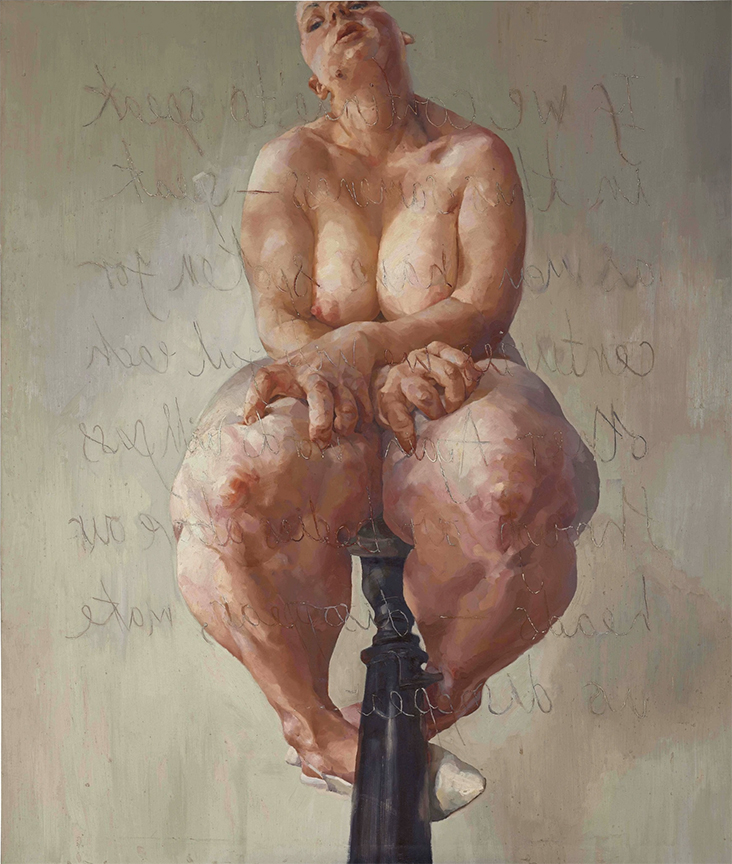

Saville’s career took off almost immediately after her degree show in 1992, when the influential art impresario Charles Saatchi bought all her paintings and commissioned her to create a body of work for his landmark Young British Artists III. Saville recalled, “He had the money and he said: make whatever you want.” Propped, 1992 is one of her best known works from this time, illustrating a nude woman perched on a tiny stool, with exaggerated, voluptuous knees, hands and thighs that seem to burst out from the canvas, while simultaneously drawing us inwards to the model’s defiant expression above. Carved into the canvas below her, in reverse is a quote by French psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray that reveals the feminist thought underpinning her practice: “If we continue to speak in this sameness – speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail eachother. Again, words will pass through our bodies, above our heads- disappear, make us disappear.” Saville originally displayed the painting facing a mirror allowing viewers to read the words, but the prop also invited them in to share this painterly space with the sitter. In these early ‘prop’ works Saville deliberately referenced Michelangelo, riffing on his “big knees coming out from stone” with her own inflated hyper-realism.

Two years after her degree show Saville took part in the Saatchi display, although her eyes were opened to the discrimination working against her when the art critic David Sylvester told her, “I always thought women couldn’t be painters,” adding, “I don’t know. That’s just the way it has always been. That’s how it is.” Even so, the blatant, sometimes shockingly aggressive nudity of Saville’s work opened up subject matter that might well have been challenging for a male artist to address, including the huge self-portrait Plan, 1993, and Branded, 1992, which showed women’s bodies marked in preparation for plastic surgery, along with Cindy, 1993, based on a woman who had pushed herself through the extremes of plastic surgery to resemble a ‘Sindy’ doll.

Jenny Saville in he studio photographed by Robin Friend / courtesy TransGlobe Publishing Ltd / reprinted from Sanctuary: Britain’s Artists and Their Studios

The paintings opened Saville up to a barrage of critical opinions, good and bad. Undoubtedly her work was picked apart for its apparent ‘body-shaming’, while some accused her of reducing women to hollow carcasses, with soulless eyes. But Saville defiantly maintained her position as an outside observer, a curious watcher of the human condition rather than a critical commentator. A number of feminist writers came out in support of her cause, celebrating her unflinching courage in taking on the male-heavy genre of nude painting, as well as her strength in confronting the painful, objectifying issues around women’s bodies and identities. American art historian Linda Nochlin wrote, “She has recreated painting in the image of our own ominous and irrational times, and that in itself is no small achievement.”

Saville was also praised by critics who saw her place in the genre of ‘post-painterly abstraction’, celebrating her ability to blend the age-old language of realist nudes with an awareness of expressive abstraction, which has remained one of her strongest legacies today. Saville has referred to this process as a willingness and courage to tear apart an image and reconstruct it, writing, “The point is that destruction is fundamental to the process; without it, you never get anywhere interesting. But fundamental to that is knowing what you can excavate from the destruction.”

In 1994 Saville visited New York on a travel fellowship, where she observed the practices of cosmetic surgeon Barry Weintraub, witnessing with fascination his patients’ desire to become “more natural” through his interventions. Gathering ideas that would make their way into her next body of work, she later produced a series of paintings featuring women covered in tape and markings in preparation for their surgery. Back then, Saville noted, drastic modifications were in the minority, but have since become much more widespread. As a further development of this project, Saville collaborated with photographer Glen Luchford to produce a series of photographs titled Closed Contact, 1995-6, in which he photographed her from below lying on a sheet of clear Perspex. Capturing her body pushed, stretched and squashed to the extremes, Saville transformed herself, too, into a sculptural form to be moulded and re-made.

In the years that followed Saville continued to search out ever more daring material, documenting and painting images related to medical pathologies, intertwined couples, mothers and children and gender pluralities. Matrix, 1999 is one of her series on transvestites, on which she writes, “I was looking for a contemporary architecture of the body…I want to be a painter of modern life, and modern bodies, those that emulate contemporary life, they’re what I find most interesting.”

As you might expect from an artist so fascinated by the human body, the experience of motherhood had a profound influence on Saville’s practice. She attributes a new form of expression, energy and fluidity to her two young children, observing, “I’m more carefree. Partly, it’s watching them – the total freedom they have, scribbling across paper … I thought: I fancy a bit of that.” She has also embraced a new plurality, combining multiple bodies together that overlap and merge into one another, a nod towards her ability to grow new life inside herself.

This, in turn, has opened up an appreciation of the ways humans intertwine and unite with one another more broadly, as seen in works with classical, erotic overtones such as Odalisque, 2012-14. Saville likens this fluidity on one hand to the porous boundaries today between real and digital worlds as she explains, “I’m trying to get simultaneous realities to exist in the same image. The contradiction of a drawing on top of a drawing replicates the slippage we have between the real world and the screen world.” But she also compares this free ambiguity to the gender diversities within so many of us that today’s society has become more willing to embrace, as she argues, “We’re made up of masculinity and femininity, so those are the things that become interesting by layering them up.”

The theme of motherhood has come to play out more openly in other works, such as the charcoal drawn series Reproduction, 2009-10 which makes a nod towards the Renaissance Madonnas of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, or in the later, gorgeously decadent Aleppo, 2017-18. In contrast with her earlier, confrontational works, these images embrace a certain tenderness and raw beauty, something she has found easier since becoming a mother, though angry lines forming tangled webs hint at turmoil beneath the surface.

Since her emergence in the 1990s Saville’s career has remained on the rise, as positive critical attention and extortionately high market prices will testify. She has become internationally recognised as one of several prominent female painters challenging and upturning the male driven realms of figurative painting, along with Marlene Dumas, Cecily Brown and Chantal Joffe. Much like her contemporaries, her ability to take risks and embrace the ever-shifting landscape of today’s human experience is what keeps her art enlivened, fresh and exciting, as she writes, “I’m really passionate about trying to make what I do relevant… It’s a risk worth taking.”

4 Comments

Pingback:

Research Point: Foreshortening – My OCA Learning LogVicki Lang

Jenny Saville paints the real world as women of today are. She has a lust for the living. Thank you for your wonderful article.

Sherry Berbit

Wow!!! Another fantastic article, which led me to discover more about Saville. truly amazing art, I’m stunned!! Thank you!

Cindy Fisher

Thank you for such a great article on this incredible artist! Very inspiring for someone like me who not only sews, but also loves art.